I’ve spent thousands of hours in grading suites, but nothing quite prepared me for the cognitive dissonance of The Act of Killing. But Joshua Oppenheimer’s film throws all those standard rules out the window. It’s a total head-trip that forced me to rethink what the camera actually does when the people in front of it aren’t just subjects, but performers of their own horrific history.

About the Cinematographer

It’s a mistake to look at this film and expect a traditional, “clean” DP credit. The visual language here was a bit of a chaotic marathon, evolving over a decade. While Lars Skree and Carlos Arango De Montis are credited, Oppenheimer was deep in the trenches himself during the early, impromptu shoots in Jakarta. You also have to remember the uncredited Indonesian crew members who had to stay anonymous for their own safety.

This wasn’t about a singular “look” established on day one. Instead, the cinematography acted as a receptive container. It adapted to the volatile environment, moving from a clandestine, fly-on-the-wall vibe to something much more ambitious as the perpetrators started “directing” their own scenes. It’s a fragmented way of working, but it’s the only way a mosaic this disturbing could have been pieced together.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The visual strategy was born out of a massive roadblock. Originally, the survivors were too terrified to talk—the killers were still in power. But when Oppenheimer approached the perpetrators, they didn’t just talk; they bragged. They wanted to show him exactly what they did, often bringing props to the actual sites of the killings.

This became the film’s conceptual blueprint. The camera had to be agile enough to catch these boastful, unscripted moments, but also ready to pivot into the “film within a film” that Anwar Congo and his crew wanted to build. The mandate was weirdly simple: “Show me what you’ve done, however you want.” So, the inspiration didn’t come from a look-book or other movies; it came from the twisted psychological state of the subjects. The cinematography had to oscillate between raw realism and a tacky, operatic style that mimicked the old gangster flicks these guys obsessed over.

Lighting Style

In the “real-world” segments the interviews and the walks through Jakarta the lighting is as raw as it gets. We’re dealing with the harsh, unfiltered Indonesian sun. From a technical standpoint, you see a lot of high-contrast, “hot” highlights and deep shadows. It feels unvarnished and practical, which is exactly what you want for a documentary it grounds the horror in a recognizable reality.

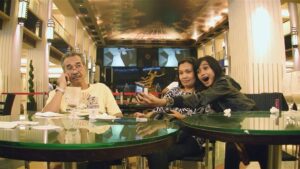

But when we flip into the reenactments, the lighting goes full-blown theatrical. It’s all about creating a spectacle. We see colored gels, neon-soaked night scenes, and that soft, almost “heavenly” backlighting in the waterfall sequence. It’s not meant to look “good” in a traditional cinematic sense; it’s meant to look like Anwar’s idea of a big-budget movie. The contrast between that gritty daylight and the garish, artificial stage lighting is a constant reminder that we’re watching a performance.

Color Grading Approach

This is where things get really interesting for me as a colorist. For the observational scenes, the grade feels intentionally neutral. I’d imagine the goal in the suite was to keep a wide dynamic range and let the natural colors of Jakarta the dusty streets and lush greens feel lived-in and maybe even a bit desaturated. You want that gentle highlight roll-off so the sun feels punishing but not “clipped” in a way that looks like bad digital.

The reenactments, though, are a totally different beast. That’s where you can see the contrast being pushed crushing the blacks and popping the whites to lean into that B-movie aesthetic. The “Heaven” scene is a prime example: you’ve got these vibrant reds and greens that feel almost nauseatingly bright against the context of what we know Anwar did. As a colorist, the “shop talk” challenge here is balancing those “tacky” oversaturated colors so they look like a deliberate choice by the perpetrators, rather than a mistake in the grade. It’s a tightrope walk making their movie look like a movie, while letting the grit of the real world seep through the cracks.

Camera Movements

The camera work is a study in controlled chaos. In the documentary portions, it’s mostly handheld and responsive. When Anwar is just walking around or Safit Padeid is extorting money from local vendors, the camera follows with a vérité intimacy. It’s a bit wobbly, a bit raw, which makes their casual assertion of power feel even more unsettling.

But once the “action” starts in the reenactments, the moves become more “cinematic” or at least they try to be. You see more considered tracking shots and even some jib-like moves to elevate the spectacle. Take the famous cha-cha dance on the rooftop; the camera moves with a fluid, almost seductive rhythm. It’s a weirdly “pretty” move for such a dark moment. That juxtaposition using a “pro” camera move to capture a man talking about his “method” for killing is a brilliant way to show how blurred the lines are between his reality and his self-serving fictions.

Lensing and Blocking

For the vérité stuff, the team stuck to a mix of wide-angle and standard lenses. It gives you enough context to see the environment but keeps a bit of a “journalist’s distance.” It keeps the depth of field deep enough so you can see the world around these men, which is important for the political context of the film.

Blocking is the most fascinating part here because, a lot of the time, Anwar and his friends are the ones doing it. They staged themselves and their “victims” (who were often just terrified locals) to look like heroes. Anwar naturally wants to be center-frame, performing for the lens. But the camera also catches the moments where that blocking fails. In the torture scenes, his body language as the “interrogator” is confident, but when he tries to play the victim, he starts to crack. He literally blocks himself into a corner, and the camera is just there to catch him finally realizing the horror of what he’s been bragging about.

Compositional Choices

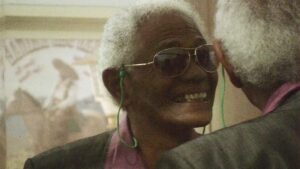

The compositions in this film are great at showing power dynamics. Oppenheimer uses a lot of wide and medium shots to place these guys in their element like showing Anwar’s wealth against the backdrop of the slums. It frames their impunity perfectly.

Close-ups are used sparingly but they hit hard. When Anwar finally starts to break down, the camera pushes in tight, isolating his face. It creates this claustrophobic feeling where you’re forced to look at his turmoil. In contrast, the reenactments are often grand and deliberately kitsch. You see characters framed “heroically” against waterfalls or burning villages. It uses strong diagonals and layered depth to mimic a gangster film. These shots aren’t just for show; they’re inviting us to question the story these men have told themselves for decades.

Technical Aspects & Tools

The Act of Killing | 1.78:1 Digital Technical Specs

| Genre | Documentary, History, Political, Docudrama, Drama |

| Director | Joshua Oppenheimer |

| Cinematographer | Lars Skree, Carlos Arango De Montis |

| Editor | Janus Billeskov Jansen, Nils Pagh Andersen, Erik Andersson, Charlotte Munch Bengtsen, Ariadna Fatj |

| Colorist | Tom Chr. Lilletvedt |

| Time Period | 2010s |

| Color Palette | Red, Green |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 – Spherical |

| Format | Digital |

| Lighting | Hard light, Low contrast |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Overcast |

| Story Location | Indonesia > Jakarta |

| Filming Location | Indonesia > Jakarta |

The production was a long haul, and you can see that in the gear. It was shot on Digital in a 1.78 aspect ratio using spherical lenses. Because it took ten years, the tech probably evolved from prosumer digital cameras to higher-end cinema rigs as the reenactments got more elaborate.

Shooting digital was the only practical choice for this kind of “embedded” filmmaking. It gave them the flexibility to shoot for hours and then show the footage back to Anwar to see how he’d react. The “raw” look isn’t a lack of craft; it’s a functional choice. The editing must have been a Herculean task sifting through years of Jakarta footage and balancing the “film-within-a-film” against the documentary. It’s not a “high-gloss” movie, but every technical choice serves the purpose of peeling back the layers of Anwar’s denial.

The Act of Killing (2012) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from The Act of Killing (2012). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: TO BE OR NOT TO BE (1942) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: THE MESSAGE (1976) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →