Some films just click. They don’t just tell a story; they possess a specific visual DNA that commands respect. Calling it a “Western” feels like a lazy categorization. It’s a pressure cooker of character dynamics and a masterclass in holding tension without a single frantic edit. The backstory alone is legendary John Wayne and Hawks basically made this as a “middle finger” to High Noon, which they viewed as un-heroic. Here, you don’t have a sheriff begging for help. You have John T. Chance: a man so stubborn he almost refuses help, fueled by a rigid professional pride. It’s a film that sits perfectly on the edge of an era, retaining the classic Hollywood glow while hinting at the grit and pessimism that Sergio Leone would soon bring to the genre. For a visual storyteller, it’s “slow, quiet, and wise,” and that’s exactly why it works.

Howard Hawks’ Visual Philosophy

By 1959, Howard Hawks had absolutely nothing left to prove. He’d already conquered noir, screwball comedy, and war films. That level of career security shows up on screen as a total lack of ego. The visual sensibility of Rio Bravo is profoundly Hawksian: the camera never shouts. While Russell Harlan, ASC, is the man behind the lens, the philosophy is pure Hawks. He trusted his actors to own the frame. Instead of “spoon-feeding” the audience with aggressive close-ups or frantic cutting, he used a naturalistic approach that forced you to actually watch the characters. You aren’t just a spectator; you’re spending time in their company, watching relationships shift through body language rather than dialogue.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The DNA of Rio Bravo comes from its narrative constraint. It’s a “Town Western” a siege movie stripped of the usual sprawling vistas. We aren’t looking at endless horizons; we’re trapped in the dusty streets of Old Tucson Studios, the saloon, and the jailhouse. This “ever-shrinking perimeter” dictates every frame.

Hawks wasn’t interested in the vast, exposed vulnerability you see in most Westerns. He wanted to visually translate the psychological weight of being cornered. By framing John T. Chance and his motley crew within these strongholds, the visual emphasis shifts from spectacle to intimacy. It’s a claustrophobic defiance. Every shot reinforces the idea that the world outside those walls is hostile, making the internal space of the jailhouse feel like the only sanctuary left in Texas.

Camera Movements

If you’re looking for virtuosic crane moves or handheld jitters, you’re watching the wrong movie. There is a deliberate, patient stillness here. The camera work is observational, moving only when a character gives it a reason to. We see pans and tilts motivated strictly by movement or a shift in dialogue.

This restraint is what gives the film its “hang out” vibe. It allows the audience to settle in and actually listen to the characters reminisce or plan their next move. In an era of over-edited, kinetic storytelling, Rio Bravo proves that the most powerful camera move is often the one you choose not to make. When the camera finally does track, it’s like a person leaning in to hear a secret. It’s subtle, unhurried, and perfectly paced.

Compositional Choices

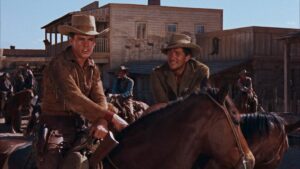

The geometry of Rio Bravo is all about the “two-shot” and the “three-shot.” Hawks and Harlan consistently keep multiple characters in the frame to maintain the group dynamic. This isn’t just about coverage; it’s about showing who is listening and who is reacting. When Dude (Dean Martin) is struggling with his sobriety, the composition ensures we see how that struggle ripples through the rest of the room.

The use of deep focus is crucial. By keeping the foreground and background sharp, Hawks could block his actors across multiple planes. You might have Stumpy guarding the rear of the jail while Chance and Feathers have a quiet moment in the foreground. It creates a layered narrative within a single static shot. Look at the wordless opening scene: the way Dude is framed retrieving a coin from a spittoon versus Wayne’s towering, stoic disapproval. No dialogue is needed because the composition tells you exactly where these men stand in the social hierarchy.

Lighting Style

The lighting is classic Hollywood, but it’s anchored by a rugged naturalism. We’re talking hard light sunny, high-contrast daylight that feels honest to the Texas setting. Every source feels “motivated.” If there’s light in the saloon, it’s coming from a flickering lantern or the harsh midday sun cutting through a dusty window.

As a colorist, I look at the density in these shadows. Even in the nocturnal saloon scenes, there’s a beautiful balance. It’s not quite noir, even if Angie Dickinson’s “Feathers” carries that femme fatale energy. The goal was clearly to maintain detail across the tonal spectrum. Harlan pushed the film stock to preserve the highlights of a lantern’s glow without letting the corners of the jailhouse turn into a muddy mess. It’s broad, enveloping light that makes the sets feel like real, lived-in environments.

Lensing and Blocking

Shooting on a Mitchell BNC in the late 50s meant the camera had a certain physical gravity. You didn’t just throw it around. The lens choices reflect that mostly 50mm “natural” focal lengths with the occasional 35mm for the street scenes. There’s no extreme distortion here; the images feel grounded, as if you’re standing five feet away from the actors.

The blocking is where the real “shop talk” happens. Hawks was a master of moving bodies within the frame to reveal power shifts. John Wayne anchors the center, while Dean Martin’s Dude literally shrinks or expands into the frame depending on his confidence level. And then you have Feathers, who moves with a fluidity that constantly challenges Wayne’s personal space. Because the shots are often medium-length and sustained, the “little bits of magic” a shared look, a subtle hand gesture have room to breathe. The shootouts are choreographed with that same clarity; you always know exactly where everyone is located in the “battle of wits.”

Color Grading Approach

Rio Bravo (1959) — Technical Specifications

| Genre | Drama, Romance, Western |

| Director | Howard Hawks |

| Cinematographer | Russell Harlan |

| Production Designer | Leo K. Kuter |

| Costume Designer | Marjorie Best |

| Editor | Folmar Blangsted |

| Time Period | 1800s |

| Color | Warm |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Sunny |

| Story Location | United States > Texas |

| Filming Location | Tucson > Old Tucson Studios |

| Camera | Mitchell BNC |

From my perspective at the grading panel, Rio Bravo is a masterclass in hue separation. The original 35mm stock had that beautiful Technicolor/Eastmancolor warmth, and the recent 4K restoration (HDR10) really highlights this. When you see the red of Wayne’s shirt against the ochres of the desert or the specific “pop” of Feathers’ yellow top, you’re seeing intentional color design.

In a modern restoration, the goal is tonal sculpting. We use HDR to expand the dynamic range revealing the grit in the sand and the texture of the jailhouse walls without losing that “print-film” sensibility. You want to maintain a healthy amount of grain to keep it feeling like a period piece. The highlight roll-off needs to be smooth and natural, avoiding that “clipped” digital look. It’s about honoring the original 1.78 aspect ratio while giving it the clarity of a modern 4K scan. We’re looking for a vibrant, clean image that still feels like it was born in 1959.

Rio Bravo (1959) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from Rio Bravo (1959). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: THE LEGEND OF 1900 (1998) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: ANATOMY OF A MURDER (1959) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →