Wim Wenders’ 1984 classic, Paris, Texas reckons with the inescapable truth that, as Confucius said, “Wherever you go, there you are.” For Travis Henderson, this isn’t philosophy; it’s a reality etched into the celluloid. The cinematography actively drives the storytelling, guiding us through an odyssey of guilt and tentative reconnection. It takes the “road movie” trope usually a symbol of boundless freedom and flips it into a relentless confrontation with past failures.

About the Cinematographer

The look of Paris, Texas belongs entirely to the Dutch master, Robby Müller. Known as the “Master of Light,” Müller avoided the over-lit, polished look common in Hollywood at the time. Instead, he favored a naturalistic approach that felt almost painterly. He didn’t just light a scene; he sculpted the atmosphere. His collaboration with Wenders created a specific visual language for outsiders. Müller understood that the environment is an extension of psychology. In this film, he gives the American desert a personality breathtakingly beautiful, yet starkly unforgiving. He trusted the silence of the actors, letting the framing do the talking.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Visually, Paris, Texas is deeply rooted in the American Western tradition, but it subverts the genre. Wenders, shifting his gaze from Germany to the US, wanted to capture the “enigmatic and solitary expanses of the American West.” Müller was the perfect collaborator for this because he shot the landscape not as a backdrop, but as a mirror for Travis’s internal turmoil.

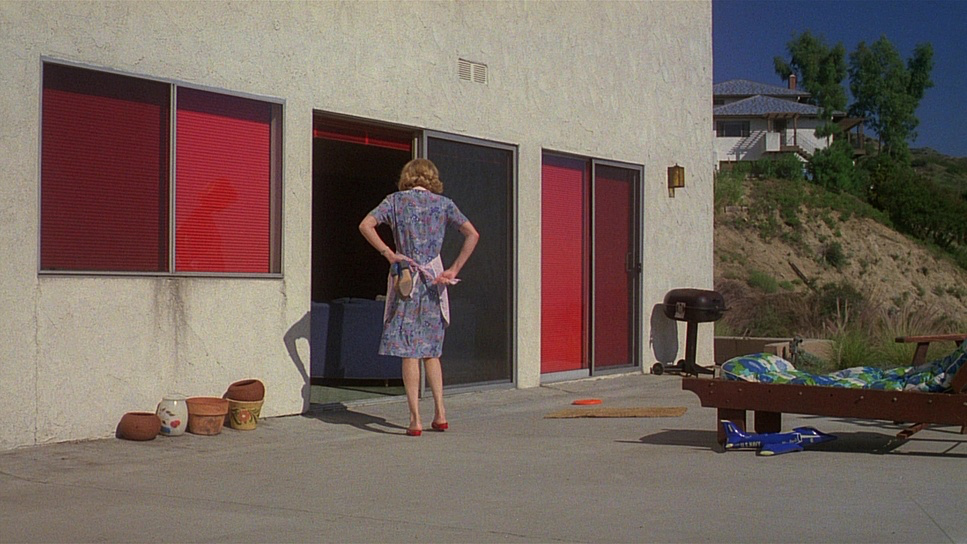

The vast vistas emphasize Travis’s four-year exile in a country where “nobody knew him.” The cinematography tackles themes of hereditary trauma and the unraveling American Dream head-on. The vibrant yet desolate Texas desert embodies Travis’s emotional state. We constantly see Travis as a small, insignificant figure against monumental backdrops, emphasizing his personal brokenness. The open road here isn’t a path forward; it’s a reminder of what he left behind.

Camera Movements

Camera movement in Paris, Texas is defined by patience. It eschews flashy declarations for subtle, observational shifts that mirror Travis’s disorientation. Early in the film, the camera remains largely static, acting as a mute witness to Travis’s wandering. When it does move, it’s often a slow, purposeful pan or a gentle dolly that emphasizes the physical and emotional distance between characters.

There is a beautiful economy to the movement. Think of the long shots as Travis and Walt drive across the country; the camera glides alongside them, allowing the scenery to breathe. Nothing feels gratuitous. A slow push-in on Travis might signal a breakthrough, while a pull-back emphasizes his smallness in a motel room. This deliberate pacing might feel slow to modern audiences accustomed to rapid cutting, but that patience allows the complex emotions to actually land.

Compositional Choices

Müller’s composition is where the film really flexes its muscles. He frequently employs expansive wide shots, placing Travis as a tiny silhouette against an endless sky or parched plain. This use of negative space is a powerful depth cue, amplifying the sense of loneliness.

But Müller was equally skilled with interiors. He uses doorways, windows, and reflections to create layers and barriers between characters. This peaks in the iconic peep show scene. The composition is masterful here: Travis and Jane are physically separated by the one-way mirror, forcing them to communicate via telephone while sitting feet apart. It visually articulates their fractured relationship. The transparency of the glass offers a superficial connection, but the framing highlights the emotional chasm. It makes the dialogue feel raw, personal, and almost voyeuristic.

Lighting Style

The lighting is a lesson in motivated naturalism. In the desert sequences, the light is harsh and unyielding. Müller let the hard sun do the heavy lifting, creating deep, crushed shadows and bright skies that convey the intensity of the heat. It’s a dynamic range decision that reflects the character’s struggle against the elements.

As Travis transitions into civilized spaces, the lighting softens. Interiors are often lit practically, with lamps and ambient window light providing a gentle, melancholic glow. The peep show scene creates a distinct mood with its dim, fluorescent-style practicals. It adds to the illicit nature of the space while allowing for moments of revelation on Jane’s face. The lighting guides the eye without screaming for attention, balancing the film’s tone between alienation and freedom.

Lensing and Blocking

Müller’s lens choices are deliberate. For the landscapes, he favored wide-angle lenses to capture the sheer scale of the desert and stretch the perspective. This subtly enhances the feeling of isolation and makes the world feel slightly off-kilter, mirroring Travis’s state of mind.

Conversely, intimate moments utilize longer focal lengths to compress space. In the peep show scene, the medium close-ups on Travis and Jane use a longer lens to bring their faces into focus despite the physical barrier of the glass. The blocking here is genius positioning them in separate booths, looking through a screen, visually communicates that they are close, yet unreachable. As Travis re-enters the world throughout the film, notice how his blocking becomes more central. He goes from hugging the periphery of the frame to occupying the center, physically demonstrating his return to agency.

Color Grading Approach

For a colorist, Paris, Texas is the holy grail. The palette is iconic. The initial desert scenes are pushed into deep, dusty ochres and rusty reds that feel almost visceral. Müller wasn’t afraid of the heat. What strikes me is the hue separation; on digital, pushing an image this warm often muddies the shadows, but here, the terracotta browns of the land remain distinct from the cerulean blues of the sky.

The highlight roll-off is something we still struggle to emulate perfectly in digital workflows. The harsh Texas sun doesn’t clip into a digital white; it blooms and feathers off gently, retaining texture. It is also worth noting that while Müller set the look on set, the pristine version we watch today owes a lot to the restoration colorist, Philipp Orgassa, who managed to keep that 1980s texture alive without sanitizing it.

Later, the palette shifts. The reds give way to the sickly, cool greens of the peep show and the neon lights of the city, reflecting a melancholic sterility. The contrast softens, but the introspection remains. The color acts as a continuous emotional barometer for Travis’s journey, shifting from the feral warmth of the wild to the artificial cool of civilization.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Paris, Texas (35mm / 1.78 Spherical)

| Genre | Drama, Road Trip, Political, Contemporary Western, Western, Comedy, Epic, Melodrama |

| Director | Wim Wenders |

| Cinematographer | Robby Müller |

| Production Designer | Kate Altman |

| Costume Designer | Birgitta Bjerke |

| Editor | Peter Przygodda |

| Colorist | Philipp Orgassa |

| Time Period | 1980s |

| Color Palette | Mixed, Saturated, Red, Green, Blue, Magenta |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting Style | Hard light, Side light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light, Mixed light, Fluorescent |

| Story Location | Houston, Suburb |

In 1984, the aesthetic was defined by the limitations and characteristics of the tools. Müller shot primarily on 35mm Eastman color negative film. The grain structure and natural color reproduction of those stocks contributed significantly to the “look.” The alchemy of photochemical development offered a texture that digital sensors still chase.

He likely used an Arriflex 35mm camera, a workhorse of that era, paired with lenses that offered character rather than clinical sharpness. The “technical aspects” weren’t just about recording an image; they were about selecting raw materials that reacted to light in expressive ways. The result is an organic quality to the light and shadow a tangible feeling that is instantly recognizable.

- Also read: THE TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE (1948) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: REBECCA (1940) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →