When you live in the world of curves and lift-gamma-gain, revisiting a film like Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972) feels less like “watching a movie” and more like a masterclass in visual intent.

It’s a profound meditation on memory and identity, It’s a film that demands you slow down, breathe, and actually see. In a world dominated by “scroll-and-swipe” content, Solaris is a necessary friction. It reminds us that every deliberate choice the choice of glass, the placement of a practical light, the final hue in the grade is a conspiracy to make the audience feel something they can’t quite name.

About the Cinematographer: Vadim Yusov

You can’t talk about Tarkovsky without talking about his eyes: Vadim Yusov. Their partnership was the kind of symbiotic relationship most of us dream of having with a collaborator. Yusov wasn’t just “executing shots”; he was sculpting the film’s emotional landscape.

If you look at his work across Ivan’s Childhood or Andrei Rublev, you see a guy who understood natural light better than almost anyone. His camera is patient. It’s an observer. He didn’t feel the need to force a scene with flashy, unnecessary movement. He let things unfold. There’s a note in some of the production transcripts where Tarkovsky mentions being “suspicious” of color early on. It was Yusov who helped him find a visual language where color wasn’t a gimmick, but a psychological tool. Together, they built a world that feels grounded in 35mm grit but stays completely unbound by the “spaceships and lasers” tropes of 70s sci-fi.

Camera Movements: A Study in Stasis

The pacing of Solaris is a middle finger to modern editing. Tarkovsky and Yusov rejected the frenetic energy we usually see in the genre. Instead, they went for a hypnotic, almost trance-like rhythm. The camera doesn’t just record; it contemplates.

Think about the infamous five-minute drive through the city (filmed in Tokyo, though it feels like a fever-dream version of the future). Most editors would have hacked that down to thirty seconds. But here, the long, slow tracking shot becomes a journey into a specific state of mind. It’s about creating space for introspection. On the station, the movements shift they become drifting, almost weightless. The camera floats through corridors, echoing the characters’ struggle to keep a grip on reality. It’s a bold, slow burn that mirrors the mystery of the planet itself.

Compositional Choices and the “Mirror”

Composition in Solaris is never “just for looks.” Yusov loved deep staging. He’d layer information within a single frame, making the space station feel claustrophobic and vast all at once.

The use of negative space is particularly haunting. You’ll see characters isolated against these huge, featureless backgrounds a literal visual shorthand for their psychological states. Then there are the reflections. Mirrors, glass, polished metal they’re everywhere. Since the character of Hari is essentially a “reflection” of Kelvin’s memory, the framing constantly blurs the line between the person and the projection. Often, Kelvin is “boxed in” by architectural lines doorways, sterile corridors visually emphasizing that he’s a prisoner of his own grief.

Lighting Style: The Texture of Reality

The lighting here is masterful precisely because it feels “unlit.” Yusov leaned heavily into motivated lighting. On Earth, he used the sun diffused, soft, and nostalgic. You can almost feel the humidity in those rain-soaked outdoor scenes.

On the station, it’s a different beast altogether. Shadows do the heavy lifting. They conceal more than they reveal, amping up the paranoia. As a colorist, I look at how they handled the practical sources those visible light fixtures and how they used them to sculpt faces against the deep blacks of the station. When Hari first appears, there’s an ethereal, almost luminous quality to the light on her. It’s not a “VFX” glow; it’s a subtle manipulation of diffusion and fill that sets her apart as something other. It’s tactile, organic, and incredibly hard to achieve without the digital safety nets we have today.

Lensing and Blocking

Yusov’s choice of glass tells the story of Kelvin’s isolation. For the Earth sequences, the wider lenses (often shot on 35mm anamorphic) give us these expansive, deep-focus views that connect Chris to nature. Everything is in focus; everything is “real.”

But on the station, the blocking becomes tight and uncomfortable. Even when Chris, Sartorius, and Snout are in the same room, they feel miles apart. The lensing keeps them at a distance. I’ve always been fascinated by how Hari’s blocking evolves. In the beginning, she’s tethered to Chris, almost like a shadow. But as she gains autonomy, her physical placement in the frame changes. She starts to occupy her own space. The blocking transcends logistics it becomes the visual map of her becoming a real person.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The core philosophy of Solaris is summed up in one of my favorite lines from the script: “We don’t want other worlds. We want a mirror.” This idea of Earth-bound narcissism drives every aesthetic choice.

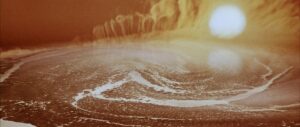

The Earth scenes are shot with a painterly reverence natural light, organic textures, flowing water. It’s a stark contrast to the sterile, “Lo-Fi” sci-fi look of the space station. This isn’t just a change of scenery; it’s a visual metaphor for humanity’s yearning for connection in an indifferent universe. The cinematography constantly asks the audience: What is real, and what is just a projection of our inner world?

Color Grading Approach: The Colorist’s View

This is where my world lives. The “grade” in Solaris is iconic, specifically the shifts between full color, sepia, and near-monochrome. Tarkovsky didn’t use these as arbitrary filters; they were tools to illustrate Chris’s moods.

From a technical standpoint, achieving these looks in 1972 meant specific film stocks and chemical processing things like silver retention or specialized baths. The sepia and monochrome sequences are mostly reserved for memories and dream states. It’s not a simple “black and white” look; it’s a carefully crafted tonal range. I look at the highlight roll-offin those scenes it’s soft, dreamlike, and fragile.

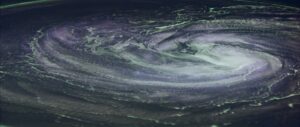

In the “present” on the station, the palette is restrained. We’re talking anemic cyans, industrial greens, and cold grays. These cooler tones underscore the sterile environment. We only see warmer, “human” tones when there’s a genuine emotional connection. Achieving that kind of hue separation on 35mm film requires an incredible amount of discipline in the production design and lighting. It’s a masterclass in using color (or the lack of it) to guide the viewer’s perception of reality.

Technical Aspects: Art over Tools

Solaris (1972) — Technical Specifications

| Genre | Drama, Lo-Fi Sci-Fi, Mystery, Science Fiction, Psychological Horror, Space, Hard Sci-Fi, Psychedelic, Science-Fiction |

| Director | Andrei Tarkovsky |

| Cinematographer | Vadim Yusov |

| Production Designer | Mikhail Romadin |

| Costume Designer | Nelli Fomina |

| Editor | Lyudmila Feiginova, Nina Marcus |

| Time Period | Future |

| Color | Saturated, Green, Blue |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.35 – Anamorphic |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light, Low contrast, Top light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Story Location | Europe > Russia |

| Filming Location | Russia > Zvenigorod |

| Camera | Rodina Camera |

Shot in the Soviet Union using Rodina cameras and 35mm stock, the technical achievements here are a testament to vision over budget. They were shooting Anamorphic 2.35:1, which gives the film that wide, cinematic stretch, but they weren’t using “clean” modern lenses. You can see the character in the glass the subtle distortions and the way it handles top-light.

The movement was achieved with dollies and custom tracks, but it has this “floating” quality that feels almost handheld at times. Every technical decision, from the choice of location (Zvenigorod for the Earth scenes) to the use of high-angle clean singles, was made to serve the philosophy. They didn’t have DaVinci Resolve or high-speed sensors. They had chemistry, light, and a deep understanding of the medium.

Solaris (1972) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from SOLARIS (1972). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: PERSEPOLIS (2007) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: THE KILLING (1956) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →