There are some films that just stay in your system. Mike Nichols’ Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) is one of them. It’s a psychological cage match where every frame feels like a calculated blow to the solar plexus. It’s been described as an “alienating piece that presents us with both reality and illusion,” and honestly, the way those two things intertwine visually is what makes it so haunting.

Nichols was a debut director here, but he didn’t play it safe. He leaned into the suffocating atmosphere of Edward Albee’s world. He used the camera as an intrusive, uninvited guest at the worst dinner party imaginable. George and Martha’s “vicious cycle of twisted games” isn’t just a script requirement; it’s baked into the shadows and the lens choices. This isn’t a stage play captured on film it’s a total cinematic transformation that strips away Hollywood glamour to find the ugly, unvarnished truth of a marriage falling apart.

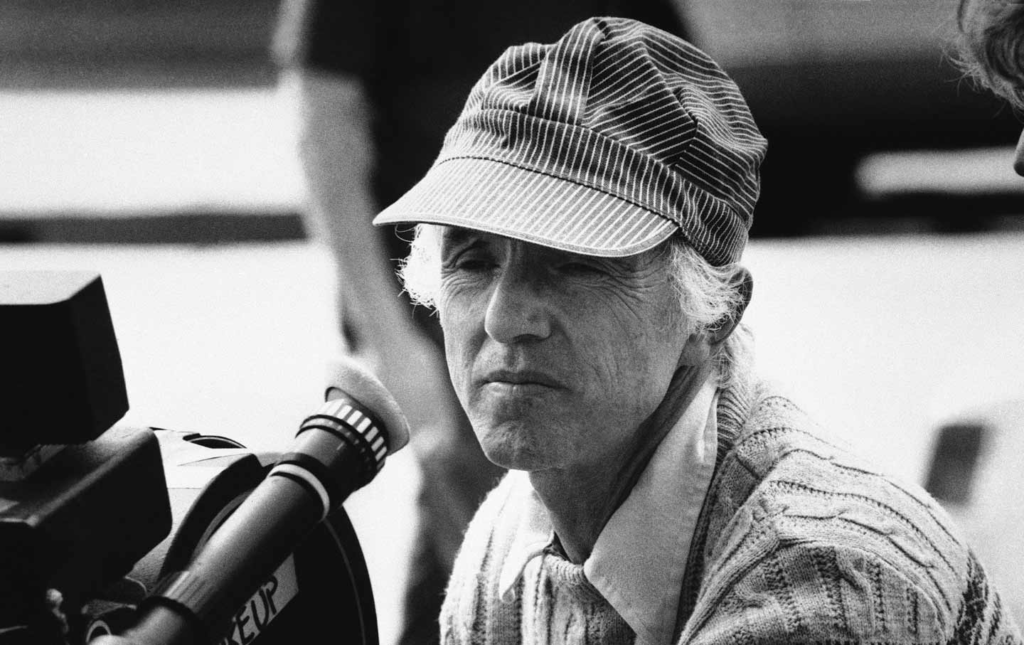

About the Cinematographer

To understand why this film looks the way it does, you have to talk about Haskell Wexler. He wasn’t just a cinematographer; he was a disruptor. Wexler had this unflinching commitment to realism. He wanted images to feel organic almost un-staged even when he was working in a highly controlled set. He was a master of natural light, but he didn’t just use it to illuminate a scene; he used it to sculpt character.

His approach was gritty and, frankly, fearless. He wasn’t interested in making Elizabeth Taylor look “movie-star pretty.” He wanted her to look “true.” That philosophy was the perfect match for Nichols’ vision. At a time when the film’s “brutal dialogue and controversial tone” were pushing sensors to the limit, Wexler was pushing the visual honesty. He brought a documentary sensibility to the house, making the rooms feel claustrophobic and the faces tell stories that the dialogue couldn’t reach. He understood that in black and white, the frame isn’t just a window it’s a reflection of the character’s internal wreckage.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The primary blueprint was Albee’s play, which is notoriously confined. The challenge for Nichols and Wexler was to break free from the “proscenium arch” without losing that visceral, trapped feeling. How do you take a screenplay that basically lives in a house and a bar and make it dynamic for over two hours?

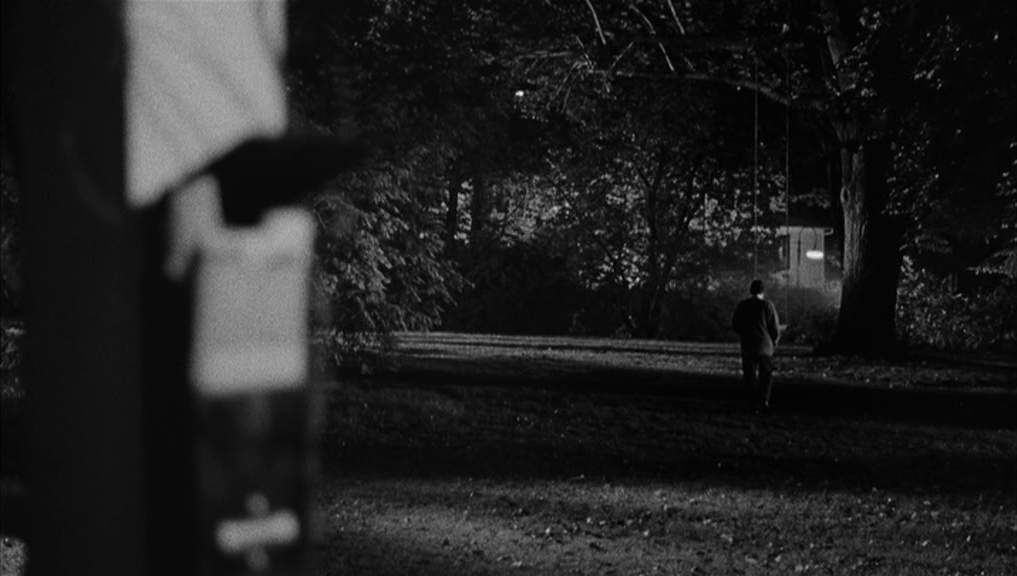

The answer was psychological realism. They weren’t just documenting an argument; they were immersing us in a labyrinth. The filmmaking had to be as alienating as the marriage itself. You can see the DNA of European art cinema here Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave. They used mobile cameras and naturalistic lighting to make the audience feel like a silent, uncomfortable witness. The house wasn’t a limitation; it was a pressure cooker. The cinematography amplifies that feeling of being unable to escape the cycle of abuse. You aren’t just watching them; you’re trapped in the room with them.

Compositional Choices

Composition here is a masterclass in tension. The framing is tight dangerously so. Nichols and Wexler frequently jam George and Martha into the same frame, yet they use the architecture of the house to keep them “alienated.” A lamp, a chair, or a sliver of shadow constantly divides them.

They also make brilliant use of depth. The house isn’t a flat background; it’s a layered, messy environment. You’ll have a character sharp in the foreground while another lingers in the mid-ground, out of focus a looming threat or a silent judge. The “poor condition” of the house, with glasses and clothes scattered everywhere, isn’t just set dressing; it’s visual commentary on Martha’s state of mind. The shots are rarely “balanced” in the traditional sense. They’re lopsided and uncomfortable, mirroring the power struggles that never quite find an equilibrium.

Camera Movements

In a dialogue-heavy film, the camera has to do more than just sit there. If it’s static for two hours, the audience checks out. In Virginia Woolf, the movement is motivated by the emotional rhythm, not just a desire for a “cool shot.”

We see these slow, deliberate pushes that encroach on a character’s personal space just as their defenses start to crack. During the “wordplay” and “emotional warfare,” the camera shifts focus with subtle pans and dollies, catching pained reactions in real-time. When things truly go “off the rails,” the camera gets restless. There’s a slight handheld sway that gives those chaotic outbursts a raw, documentary immediacy. When George delivers a monologue, the camera might isolate him completely, cutting him off from the world, or drift to Martha to catch a flicker of vulnerability behind her mask. It’s surgical filmmaking.

Lighting Style

This is where Wexler really shines. He leaned into motivated lighting practical lamps, fireplaces, and windows. It wasn’t about “studio pretty”; it was about authenticity.

The film is high-contrast and brutal. The shadows are deep, often swallowing half a face to create a Chiaroscuro effect that screams “fractured psyche.” As a colorist, I look at this and see a brilliant use of the “toe” of the film curve letting things fall into black to hide secrets and create havens for resentment. The lighting plays directly into the “truth and illusion” theme. Harsh light exposes the “harrowing tales,” while pockets of shadow allow the illusions to survive a little longer. It’s a visual boxing match where the light and shadow are the punches and counter-punches.

Lensing and Blocking

Lensing and blocking are the invisible architects of the power dynamics here. Given the tight spaces, Wexler likely leaned on wider lenses to keep multiple characters in the frame without losing the oppressive feeling of the room. It allows for a “visceral dance” where characters circle each other like gladiators.

Blocking is used to show aggression and retreat. George might dominate the physical space one moment, standing over Martha, only for her to reclaim it seconds later. The close-ups are treated like weapons. When a line is particularly cruel, the lens tightens, forcing us into the character’s emotional core. Elizabeth Taylor’s “parking lot” scene the most dramatic moment in the film is a testament to how precise lensing can magnify raw despair. Wexler ensured that every nuance of Richard Burton’s “pitiful man” was captured with unflinching detail.

Color Grading Approach

Even though this is a black and white film, my “colorist heart” sees this as a triumph of tonal sculpting. I don’t see a “lack of color”; I see the profound impact of luminance and texture.

Shot on 35mm, the film has those beautiful “print-film” sensibilities nuanced highlight roll-off and inky, satisfying blacks. In the grading suite, my job would be to protect that grain and the “dynamic range decisions” Wexler made. The contrast isn’t static; it oscillates. When George and Martha are tearing into each other, the contrast peaks, making them look almost skeletal. In moments of exhaustion or vulnerability, the tonal range softens, using different shades of grey to define their isolation. The shadows have texture; the highlights illuminate harsh realities. It’s tonal storytelling at its peak.

Technical Aspects & Tools

In 1966, choosing black and white wasn’t about saving money it was a defiant artistic statement. It allowed Nichols and Wexler to bypass the “garish” color processes of the time and achieve something timeless and stark.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

| Genre | Drama, Stage Adaptation, Suburbia |

| Director | Mike Nichols |

| Cinematographer | Haskell Wexler |

| Production Designer | Richard Sylbert |

| Costume Designer | Irene Sharaff |

| Editor | Sam O’Steen |

| Time Period | 1950s |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, High contrast, Top light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light |

| Story Location | … United States of America > New England |

| Filming Location | … Burbank > Warner Brothers Burbank Studios |

| Camera | Eclair Cameflex CM3 |

| Lens | Angenieux – HR Zoom – 25-250mm |

Wexler worked with 35mm cameras like the Arriflex or Mitchell, and his choice of stock (likely Kodak Double-X) provided that specific grain structure. That stock rendered skin with a sculptural quality that digital struggles to replicate. He probably used filters like red filters for exteriors to manipulate the sky and contrast. But ultimately, the tech was secondary to the intent: to deliver an unvarnished portrait of human anguish. For this film, black and white wasn’t a limitation; it was a liberation.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: PINK FLOYD: THE WALL (1982) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: SPRING, SUMMER, FALL, WINTER… AND SPRING (2003) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →