Throne of Blood. Or, if you want to get specific, Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 masterpiece Spider Web Castle. I’m constantly looking at how a director manages to weave intent into the very grain of the image, and Kurosawa’s work here is as audacious as it gets.

He didn’t just adapt Macbeth into feudal Japan; he rebuilt it from the ground up to reflect a world reeling from the aftermath of war. It’s a moralistic vortex, or as one analysis put it, a study of the “unending, unchanging, depraved human heart.” Every time I sit down with this film, I find a new layer of psychological genius hidden in the shadows. Honestly, it’s one of those rare pieces of cinema that actually rewards you for being obsessive about the details.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

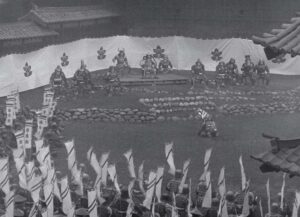

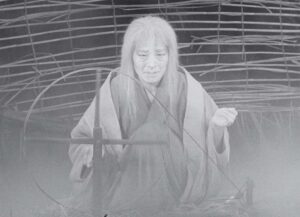

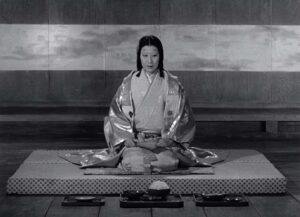

The DNA of Throne of Blood is essentially a collision between Shakespearean drama and the rigid, ghostly world of Noh theatre. This isn’t just a “vibe” it’s the literal architecture of the film’s visual grammar. You see it in the stylized, almost ritualistic movement of the actors, particularly Isuzu Yamada as Lady Asaji. Kurosawa reportedly told her to emulate the literal masks worn by Noh performers, and the camera treats her accordingly: static, central, and haunting.

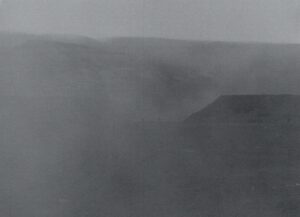

Then there’s the environmental grit. This film was released in 1957, a time when the “depraved human heart” wasn’t just a poetic concept but a reflection of post-WWII anxiety. The fog and wind aren’t just weather effects; they are characters. They represent the disorientation of the era the uncertainty of where you are or who you’ve become. The “Spider Web Forest” isn’t just a location; it’s a visual metaphor for entrapment that Nakai and Kurosawa used to box the characters in.

About the Cinematographer

Now, while many people immediately think of Kazuo Miyagawa when they hear “Kurosawa,” the visual architect here was actually the legendary Asakazu Nakai. Nakai was a beast in his own right, lensing everything from Seven Samuraito Ran.

Where Miyagawa was known for that painterly, lyrical quality, Nakai brought a certain rugged, atmospheric intensity to Throne of Blood. He had to translate Kurosawa’s obsession with Noh theatre into a cinematic language that felt both ancient and immediate. His ability to capture the texture of the fog making it feel thick, wet, and oppressive is what gives this film its visceral edge. He wasn’t just shooting a play; he was capturing a nightmare.

Lighting Style

In the black-and-white world of Throne of Blood, lighting is the narrative. Nakai’s approach is a masterclass in chiaroscuro, using high-contrast lighting to sculpt the psychological landscape.

The fog acts as a massive natural softbox, but the way they used volumetric light is what kills me. You see these “floating torches” or beams of sunlight struggling through the mist, creating a tangible sense of depth. For Lady Asaji, the lighting is often hard and directional, emphasizing that mask-like face and creating deep, hollow shadows in her eyes. It’s highly expressionistic every shadow feels like it’s hiding a secret, and every highlight feels like a moment of terrifying clarity.

Color Grading Approach

As a colorist, looking at a 1957 B&W print like this makes my fingers itch for a DaVinci panel. Even without hue or saturation, the tonal sculpting here is incredible. If I were grading this today, my main goal would be preserving that “inkiness” in the blacks without losing the detail in the shadows what we call “crushing” the blacks.

I’d be obsessing over the highlight roll-off. In those foggy exteriors, you need a beautiful, gentle transition from the whites to the midtones to keep that ethereal, “silvery” film look. I’d also look at the midtone density; a great B&W image is really just an expansive palette of greys. Nakai likely used yellow or red filters on set to manipulate how colors translated into grey values effectively doing “hue separation” in-camera. My job in a digital suite would be to honor that organic grain and ensure the contrast curve feels as timeless as the original 35mm stock.

Compositional Choices

Kurosawa’s compositions are basically a masterclass in tension. He loves centered compositions that feel formal and theatrical, echoing the Noh influence. It makes the frames feel symmetrical and grand, but also incredibly suffocating.

However, the real magic happens when they use asymmetrical framing to show Washizu’s sanity slipping. As his world falls apart, the frame loses its balance. My favorite thing about the composition here is the depth cues. Miyagawa and Nakai layered the frame with trees, architectural beams, and fog to create a sense of being “cornered.” You’re never just looking at a character; you’re looking at a character trapped inside a maze of visual layers.

Camera Movements

The camera movement in Throne of Blood is a weird, beautiful dance between “shocking stillness” and “kinetic energy.”

On one hand, you have these massive, static wide shots where the characters look like ants against the landscape. These long takes some lasting three minutes force you to sit with the paranoia. But when things go south, the camera gets “panicked.” We see shaky, fast-paced motion and rapid pans that mirror Washizu’s anxious mind. It’s a brilliant way to disrupt the formal Noh stillness, signaling his descent into madness.

Lensing and Blocking

Kurosawa was famous for his love of long telephoto lenses, and you see that all over this film. It does two things: it gives the actors space to perform without a lens in their face, and it compresses the perspective.

That lens compression is key. It makes the background feel like it’s pressing in on the foreground, making the castle walls feel closer and the fog feel thicker. The blocking is just as meticulous. Lady Asaji is almost static, moving with a chilling, ritualistic precision, while Washizu becomes increasingly erratic and animalistic. Every entry and exit from the frame feels like a move on a chessboard.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Throne of Blood | Technical Specifications

| Genre | Drama, History, Stage Adaptation, Shakespeare on Screen |

| Director | Akira Kurosawa |

| Cinematographer | Asakazu Nakai |

| Production Designer | Yoshirô Muraki |

| Costume Designer | Yoshirô Muraki |

| Editor | Akira Kurosawa |

| Time Period | Renaissance: 1400-1700 |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.37 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light, Low contrast |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Overcast |

| Story Location | Asia > Japan |

| Filming Location | Tokyo > Toho Studios |

For 1957, the tech here is staggering. They were shooting on 35mm film (likely Kodak Double-X or a Japanese equivalent), which provided that grit and latitude we still try to emulate today.

But the real “tech” was the practical effort. There was no CGI. To get “one of the windiest movies ever made,” they used massive industrial fans and constant smoke machines. Controlling that much fog on location is a logistical nightmare it affects how light penetrates the scene and how you block your actors. It’s a testament to an era where if you wanted a specific atmosphere, you had to physically build it and capture it in-camera.

Throne of Blood (1957) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from THRONE OF BLOOD (1957). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: CITIZENFOUR (2014) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: THE TALE OF THE PRINCESS KAGUYA (2013) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →