Sam Peckinpah’s 1969 masterpiece, The Wild Bunch, is unequivocally one of them. For me, dissecting its cinematography isn’t some dry academic exercise; it’s a deep dive into craft, intuition, and the raw, emotional logic of visual storytelling.

When I first encountered The Wild Bunch, the impact was immediate and, honestly, a bit jarring. It wasn’t just the controversy around the violence though that obviously played into the film’s notoriety. It was the audacious way it blew up every expectation of the Western. By 1969, the genre was facing a serious reckoning. The world was upside down Vietnam, social unrest, a total erosion of trust. Cinema had to reflect that. We were moving away from the “white hat sheriff” and toward something much more complex and anti-authority. The Wild Bunch didn’t just push the envelope; it tore it wide open, exposing a brutal, beautiful, and deeply melancholic vision of a dying era. Underpinning every single frame was Lucien Ballard’s magnificent cinematography.

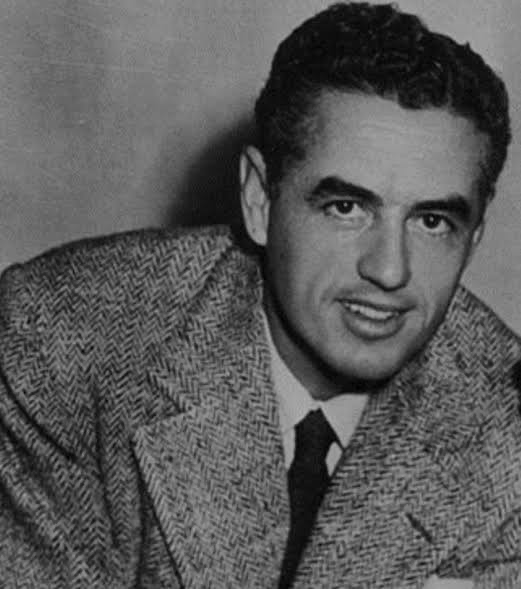

About the Cinematographer

The man behind the glass was the legendary Lucien Ballard. Now, Ballard wasn’t some new kid on the block; he’d been around for decades, shooting everything from film noir classics like The Killing to standard-issue Westerns. But what’s fascinating is how he adapted his “old school” seasoned skills to Peckinpah’s revolutionary (and often chaotic) vision.

He wasn’t interested in “pretty” pictures here. He was capturing the grime, the sweat, and that specific brand of desperation that follows “men out of time.” His collaboration with Peckinpah was pivotal. He took a brutal, nihilistic script and translated it into a visual language that was equally harsh but somehow undeniably poetic.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Peckinpah’s goal was clear: he wanted to dismantle the romanticized myth of the Old West. He was sick of the sanitized, bloodless gunfights you’d see on TV. With the Vietnam War playing out on the nightly news, he felt cinema needed to catch up to actually show the audience what it was like to be gunned down.

This drive for realism wasn’t just for shock value; it was a moral choice. It’s why Ballard rejected the clean, heroic framing of traditional Westerns. Instead, the camera had to feel immersed, sometimes even frantic. They chose the gritty Mexican desert specifically for its authenticity, demanding a naturalistic approach to lighting that threw the glossy, studio-bound aesthetic out the window in favor of something raw and unvarnished.

Lighting Style

The lighting in The Wild Bunch is where you really see Ballard’s commitment to realism. Since they were filming on location in Mexico often in towns that didn’t even have electricity he had to lean into the harsh, unforgiving desert sun.

As a colorist, I love the way he handles the dynamic range here. You see deep, unapologetic shadows and stark contrasts. This isn’t “glamour” lighting; it’s survival lighting. When they move indoors like the brothel or the General’s headquarters the light feels motivated by practicals: candles or oil lamps. It grounds the scene in a period-appropriate reality. There’s a robust, filmic texture to the images that tells you everything you need to know about the heat and the dust these men live in.

Lensing and Blocking

We have to talk about the anamorphic lenses. That 2.39:1 aspect ratio is the unsung hero of the film. It creates this massive canvas that allowed Ballard to compose shots with incredible depth. You get the full scope of the Mexican landscape, but he still keeps the characters sharply in focus in the mid-ground.

The blocking is just as impressive, especially in those large-scale action set pieces. Peckinpah and Ballard orchestrated these “ballets of violence” with multiple cameras, ensuring every angle hit with a visceral impact. The choice to use weathered, older actors men with what Tarantino called “sagging bellies and sagging tits” was a stroke of genius. Their physical presence in the frame makes their “old bag” status feel authentic and earned.

Compositional Choices

Ballard’s compositions do a lot of the heavy lifting when it comes to the film’s themes of isolation and brotherhood. He constantly uses wide shots to dwarf the characters against the desolate landscape, emphasizing how insignificant they’ve become in a changing world.

But when the tension ramps up, Ballard pulls in tight. He uses framing that feels almost claustrophobic, trapping the characters in their own bad choices. One of my favorite examples of visual economy is the scene where the children are torturing scorpions; it’s composed so simply, yet it foreshadows the corruption and violence to come. The anamorphic glass allowed for complex group blocking, letting multiple characters share the frame during confrontations without things feeling cluttered.

Camera Movements

The camera in The Wild Bunch isn’t just watching the story; it’s caught in the middle of it. Ballard used a mix of kinetic and very deliberate movements to keep the audience off-balance. During the infamous Starbuck massacre, the camera is frantic tracking escapees, panning rapidly, dodging bullets.

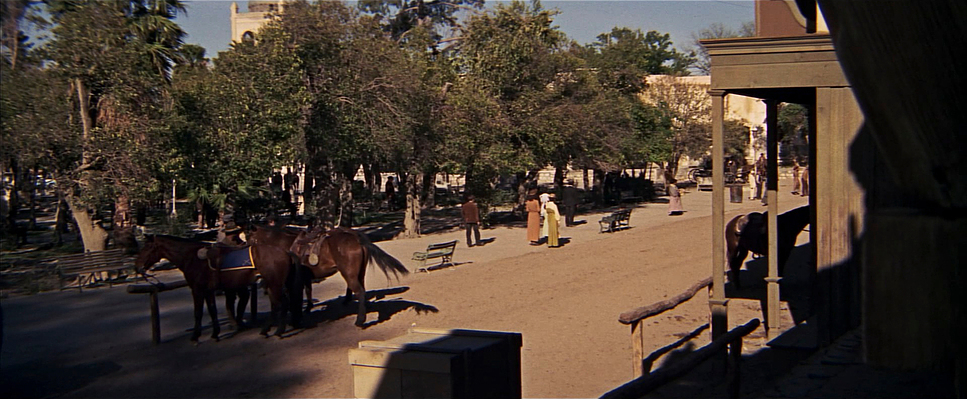

But then, you have moments of profound stillness. Think about that final, iconic walk through Mapache’s town. The camera adopts a slow, mournful tracking shot. It’s a solemn procession. The weight of their past is palpable in every measured step. That juxtaposition explosive chaos followed by a heavy, balletic walk creates a rhythm that’s unlike anything else in the genre.

Color Grading Approach

This is where my mind really starts humming. Even though I’m working in a digital suite today, I’m always chasing the sensibilities of those original 1969 film prints. The Wild Bunch has this wonderfully earthy, desaturated palette sun-baked browns, dusty ochres, and muted greens. There are no “candy-colored” explosions here.

If I were grading a contemporary scan of the original negative today, my priority would be preserving that print-film aesthetic. I’d want to maintain that specific highlight roll-off and the slightly crushed shadow detail that gives the film its grit. The reds (the blood) need careful handling. They shouldn’t look “pretty” or cartoonish; they should look shocking, just like Peckinpah intended. It’s about leaning into that warm, golden-hour light while keeping the underlying grittiness that makes the world feel lived-in.

Technical Aspects & Tools

The Wild Bunch (1969)

To get that level of visceral action, they had to innovate. Peckinpah famously used multiple cameras filming at different speeds simultaneously anywhere from 120fps to 2fps. This gave the editors the raw material for those groundbreaking slow-motion bursts that made the violence feel agonizingly drawn out.

But it wasn’t just the visuals. Peckinpah was obsessed with the “sound” of the West. He hated stock gunfire sounds, so his team went to extreme lengths to record accurate sound effects for every specific caliber of weapon used. Between that meticulous audio work and Jerry Fielding’s purposeful score, the film becomes a full-sensory experience. They even filmed in Mexican towns without electricity just to ensure the environment felt anachronistic and real.

The Wild Bunch (1969) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from The Wild Bunch (1969). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: THE BIG SLEEP (1946) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: SHORT TERM 12 (2013) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →