The Pursuit of Happyness (2006) doesn’t rely on flashy look-at-me visuals; instead, it uses cinematography to mirror Chris Gardner’s exhaustion. It resonates with me not just for the narrative of resilience, but because the choices made in the camera department and the grading suite are so disciplined. The filmmakers resisted the urge to glamorize poverty, opting for a visual language that feels heavy, lived-in, and unmistakably human.

About the Cinematographer

The visual landscape was crafted by Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC, a DP known for his chameleon-like ability to serve the story. If you look at his later work, from the sharp black-and-white of Nebraska to the vintage gloss of Ford v Ferrari, you see a range that few possess. But here, Papamichael strips everything back. His approach in The Pursuit of Happyness is devoid of ego. He avoids overt stylization in favor of a raw, observational quality that forces us into the uncomfortable reality of 1980s San Francisco. It’s a specific kind of naturalism that feels immediate, almost like a documentary of a life unraveling in real-time.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The visual style stems directly from the “meaningful obstacles” embedded in the script. This is a rags-to-riches story, sure, but the camera focuses entirely on the “rags” portion of that equation. We aren’t watching abstract plot points; we are watching a man drowning in a system designed to keep him out.

The visual storytelling had to convey a constant uphill battle. Every challenge Chris faces from the bone density scanners that become physical burdens to the race for a bed at the Glide Memorial United Methodist Church is visually anchored in a harsh reality. The imagery isn’t aspirational; it’s claustrophobic. The goal was clearly to place the audience inside Chris’s headspace, to make us feel the “personal pain of his reality not matching his vision.” The cinematography translates that internal conflict into external pressure, using the environment of the city not as a backdrop, but as an antagonist.

Camera Movements

The camera work in this film balances panic with paralysis. Papamichael utilizes a lot of handheld operating, but it’s not the shaky-cam action style that became popular later in the 2000s. It’s a breathing, reactive handheld that suggests instability.

When Chris is sprinting through the streets of San Francisco, late for an appointment or chasing a stolen scanner, the frame jostles with him. It gives us a subjective viewpoint of his lack of control the relentless forward momentum dictated by survival. The camera pace matches his stride, creating a genuine anxiety during those daily scrambles to the shelter.

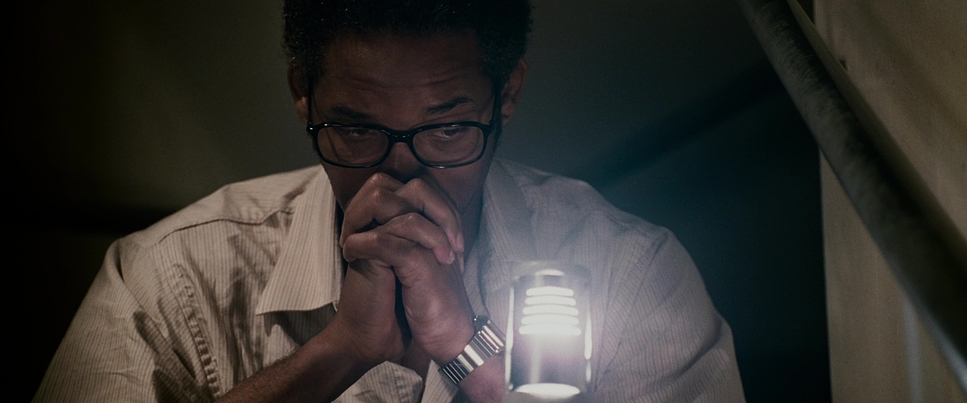

In contrast, the scenes of defeat are marked by a suffocating stillness. When Chris and his son are locked in the train station bathroom, the camera stops moving. It locks off. That static framing emphasizes their entrapment better than any dialogue could. The contrast between the frantic energy of the day and the dead stillness of the night creates a rhythm that charts his emotional exhaustion.

Compositional Choices

The 2.39:1 aspect ratio is used brilliantly here. Usually, anamorphic widescreen is used for epics, but here, it emphasizes isolation. In wide shots, the negative space dwarfs Will Smith against the imposing architecture of the financial district. He is frequently framed at the bottom or far edges of the frame, visually reinforcing his smallness against the indifference of the city.

Conversely, when the pressure mounts, the framing tightens aggressively. Papamichael uses long lenses to compress the background, making the world behind Chris feel chaotic and blurry, while his face is sharp and inescapable. In the interview scene where he shows up covered in paint and underdressed, the close-ups are unforgiving. The shallow depth of field isolates him from the panel of interviewers, highlighting his “shabby clothes” against their crisp suits without needing a wide shot to show the difference.

The relationship with his son, Christopher Jr., dictates a different compositional logic. They are almost always framed together as a single unit. Even in the widest shots of the homeless shelter lines, they are visually tethered, highlighting that amidst the vast, uncaring crowd, their only sanctuary is each other.

Lighting Style

The lighting is strictly motivated and largely relies on available light principles. Papamichael avoids the “Hollywood sheen.” If a scene takes place in a shelter bathroom, it looks like it’s lit by cheap, green-spiked fluorescent tubes. If it’s an overcast day in San Francisco, the light is flat and diffuses deeply into the shadows, offering no punch or contrast.

This dedication to naturalism means the lighting is rarely “flattering” in the traditional sense. When they are homeless, the light levels drop, and the image gets murky. It feels cold. The lack of a strong key light or a rim light to separate them from the background reinforces their situation they are blending into the shadows of society.

However, lighting is also used as a narrative marker. The scene where Chris fixes the scanner and the bulb finally glows is a perfect example. That warm, tungsten light popping in a cool, dim room isn’t just a practical source; it’s the first visual spark of hope we’ve seen in an hour. It cuts through the drab environment, signaling a shift in his luck.

Lensing and Blocking

Shooting on Panavision glass, the lensing choices favor the telephoto end of the spectrum. Long lenses do two things here: they compress the distance between Chris and his goals (making the stockbrokers seem close yet physically unreachable), and they allow the camera to hang back, observing from a distance like a passerby. It adds to the voyeuristic, unvarnished feel of the film.

The blocking how the actors move within that space is precise. In the Dean Witter offices, Chris is often blocked to stand apart from the hive of activity. He is static while the brokers swirl around him. In the interview scene, despite his appearance, the blocking places him centrally. He doesn’t cower in the corner; he holds the center of the frame. It’s a subtle visual cue that despite his exterior, he possesses the internal gravity of a man who belongs there.

Color Grading Approach

This is where I really geek out. The grade on The Pursuit of Happyness is a textbook example of 35mm print emulation done right. The palette is distinctly desaturated, but not in a digital, monochromatic way. It leans into the color science of film stocks from that era likely Kodak Vision2 where the shadows carry a fair amount of density and grit.

The film rests heavily in the toe of the curve. The shadows aren’t crushed to a perfect digital black; they sit in a murky, dark grey zone, often with a slight cool-green bias that creates a sense of unease and institutional coldness. This is crucial for the first two-thirds of the film. The world through Chris’s eyes is drained of vibrancy.

The highlight roll-off is where the Panavision optics and film acquisition really shine. You don’t get that harsh digital clipping on the windows or the sky; the highlights taper off gently, keeping the image organic even when the contrast is high. As the narrative shifts and Chris begins to succeed, the grade subtly warms up. We start seeing cleaner skin tones and a move away from the green/cyan overcast feel toward warmer ambers. It’s not a slap-in-the-face change, but a gradual lift in the mid-tones that subconsciously tells the audience: breathe, he made it.

Technical Aspects & Tools

The Pursuit of Happyness — Technical Specs

| Genre | Drama, Family, Fatherhood, Business |

| Director | Gabriele Muccino |

| Cinematographer | Phedon Papamichael |

| Production Designer | J. Michael Riva |

| Costume Designer | Sharen Davis |

| Editor | Hughes Winborne |

| Colorist | John Persichetti |

| Time Period | 1980s |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.39 |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Overcast |

| Story Location | … California > San Francisco |

| Filming Location | … San Francisco > 555 California Street Building |

| Camera | Panavision Cameras |

| Lens | Panavision Lenses |

The film was shot on 35mm film using Panavision cameras and lenses, and the texture is undeniable. In 2006, digital cinema was in its infancy, and shooting strictly on film provided a dynamic range that was essential for a production relying so heavily on natural daylight.

Film stock has a forgiving latitude in the highlights that allowed Papamichael to expose for the shadows in those dark alleyways without completely blowing out the San Francisco sky. The grain structure is visible, adding a tactile layer to the image that implies grit and struggle something that a clean digital sensor might have rendered too clinically. The 2.39 aspect ratio (Scope) was a bold choice for a drama, but it was necessary to capture the horizontal sprawl of the city streets and the crowds, emphasizing just how many people Chris had to push past to survive.

- Also read: BLOOD DIAMOND (2006) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: 12 MONKEYS (1995) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →