Lately, I’ve been spending a lot of time staring at the grain structures of early cinema. It started as a technical curiosity, but it quickly led me back to the foundations the “ur-movies” that established the grammar we take for granted today. That journey invariably ends at Charlie Chaplin, and specifically, his 1921 masterpiece, The Kid.

It’s easy to dismiss silent films as archaic, but watching The Kid isn’t just a history lesson; it’s a masterclass in efficiency. Chaplin didn’t just mix comedy and drama; he proved they were two sides of the same coin. He showed us that a static wide shot could be funnier than a close-up, and that lighting could tell a joke. For a filmmaker, revisiting this film is a dialogue with a foundational text, a way to understand how visual choices made a century ago still inform how we cut and grade today.

About the Cinematographer

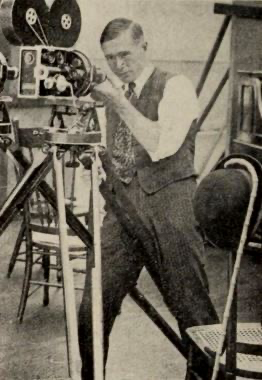

You can’t talk about the look of The Kid without acknowledging Chaplin’s total control he wrote, directed, produced, scored, and starred in it. But the person responsible for ensuring that meticulous vision actually hit the negative was Roland Totheroh.

Totheroh was Chaplin’s visual anchor. He wasn’t a showy cinematographer hunting for the perfect flare; he was a technical surgeon. He understood that in a Chaplin film, the camera needed to be invisible. His job wasn’t to distract the eye, but to build a frame where the choreography could breathe. From 1915’s His New Job to 1952’s Limelight, Totheroh was the one capturing the internal rhythm of the Tramp, ensuring that every pratfall and every tear landed with maximum clarity. He provided the visual stability that allowed Chaplin’s chaos to thrive.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The visual language here is deeply personal. Chaplin grew up in the poverty of London, and that experience bleeds into the stark portrayal of the slums where the Tramp and Kid live. The cinematography had to do heavy lifting: it needed to convey squalor and struggle without losing the warmth of the central relationship.

It’s a balancing act. The film opens with a “Fallen Woman” narrative heavy, melancholic which sets a visual tone of stark class division. We see a society split visually: the grimy texture of the back alleys versus the soft, clean luxury of the wealthy world. The camera isn’t just recording a set; it’s commenting on social structure. The composition constantly emphasizes barriers gates, doors, and walls highlighting the struggle to cross from the “lowest class” to a better life.

Camera Movements

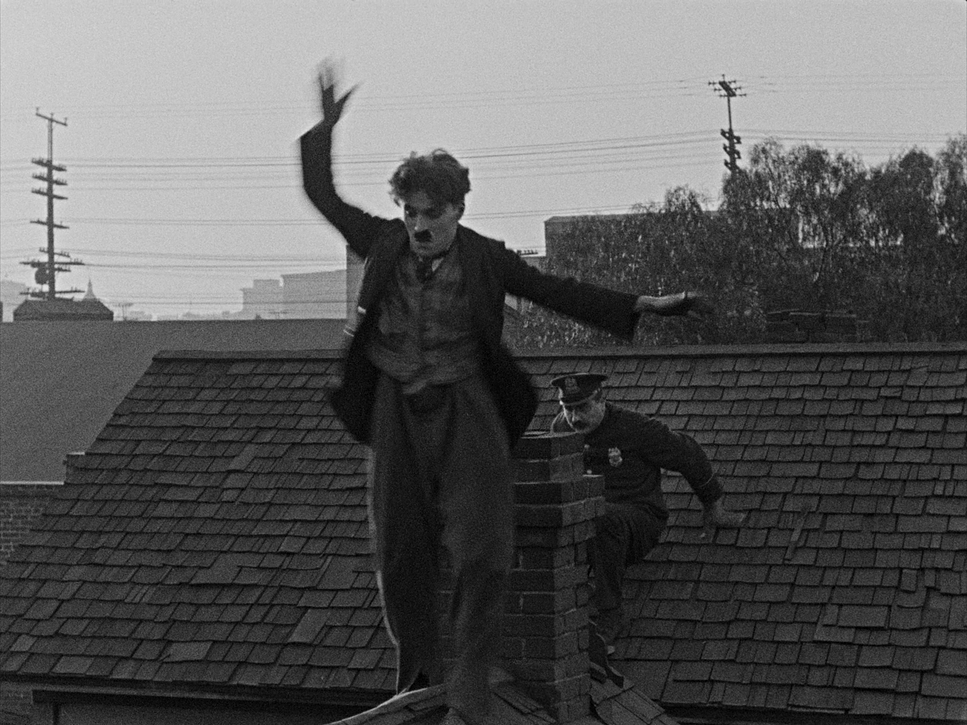

In 1921, the camera was usually a heavy, fixed observer. Totheroh and Chaplin leaned into this constraint. For the broad physical comedy, the static wide shot is king. It creates a proscenium arch, allowing us to see the full body mechanics of Chaplin and Jackie Coogan without a shaky camera ruining the timing.

But watch closely during the climax, specifically the orphanage chase. The static rule breaks. We get tracking shots or more accurately, frantic pan-and-tilt movements following the Tramp’s pursuit across rooftops. These aren’t polished dolly shots; they are desperate. The camera becomes an extension of the Tramp’s panic. The movement is earned. Because the rest of the film is so locked down, when the camera does move, it hits the audience with a visceral sense of urgency.

Compositional Choices

Even with a static camera, the framing in The Kid is incredibly active. Chaplin and Totheroh used the arrangement of elements within the frame to dictate the emotion.

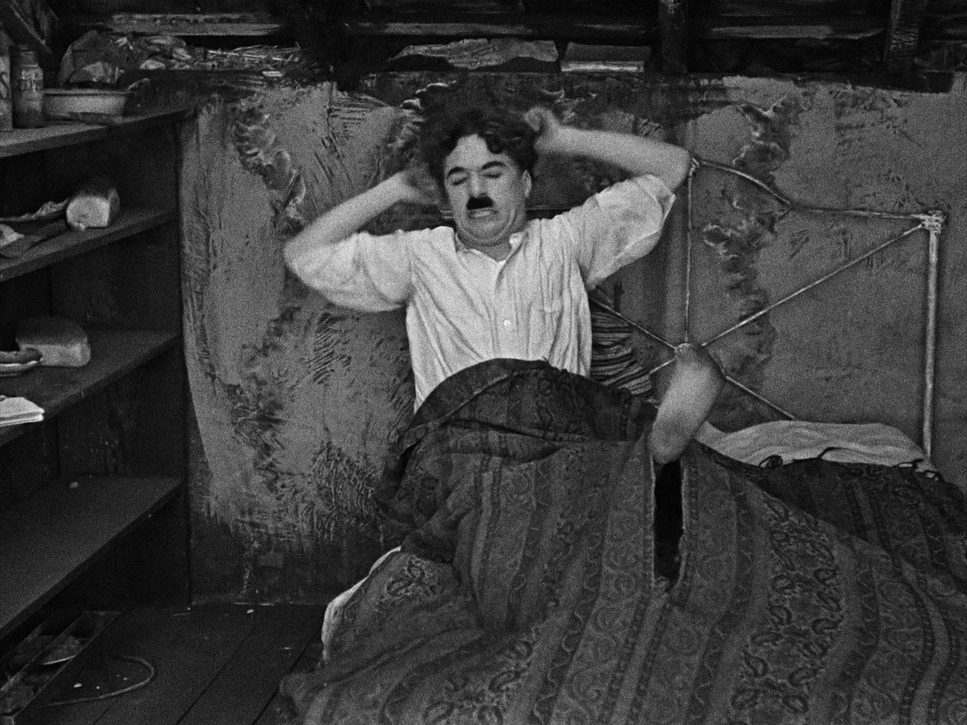

There is a constant push-and-pull between isolation and unity. When the Tramp and Kid are in their cramped apartment or navigating the streets, the wide framing emphasizes their smallness against the uncaring, massive city. But when the emotional beat hits, the frame tightens. It draws a circle around them, creating a self-contained world.

The use of “portals” is another brilliant compositional tool. The film is obsessed with thresholds doorways, windows, alley entrances. The framing constantly reinforces who is allowed inside and who is kept out, turning simple architecture into narrative tension. And notice the close-ups on Jackie Coogan; the camera pushes in just enough to catch the raw anguish on his face, proving that a child actor could hold the screen against the biggest star in the world.

Lighting Style

Lighting in the 1920s was a battle against slow film stocks and harsh equipment. For exteriors, Totheroh relied heavily on natural sunlight, often using large diffusers to soften the blow. This gives the street scenes a flat, almost documentary-like realism that grounds the slapstick in a recognizable reality.

Interiors are where the lighting gets more deliberate. It’s not the three-point lighting we use today; it’s motivated and moody. The apartment scenes often suggest a single light source a window or a lantern creating deep pools of shadow. This chiaroscuro effect does two things: it hides the cheapness of the set, and it emphasizes the intimacy of the space.

The dream sequence, however, breaks the rules entirely. The lighting shifts from gritty realism to a soft, ethereal glow. It’s distinct, likely achieved with heavy diffusion and controlled artificial sources. It visually signals to the audience that we have left the cold reality of the slums and entered the Tramp’s subconscious.

Lensing and Blocking

We aren’t dealing with zoom lenses or complex racks here. Totheroh likely used standard prime lenses 35mm or 50mm equivalents that mimic the human field of view. This normality is crucial; it makes the absurdity of the comedy feel real.

The real special effect in The Kid is the blocking. Chaplin was a master of staging action within a fixed frame. Take the famous window-breaking scheme: the Kid breaks a pane, the Tramp appears to fix it. The camera doesn’t cut; the comedy relies entirely on the precise timing of actors entering and exiting the frame. It’s a dance. The wide shots allow the actors to use the entire depth of the room, creating a dynamic visual experience without the camera operator having to do a thing.

Color Grading Approach

This is where I put my colorist hat on. If I were restoring The Kid today, or grading a modern film trying to emulate it, I wouldn’t just desaturate the footage and call it a day. The “color” of a black-and-white film is in its density.

I’d be looking at the tonal sculpting. We’re dealing with the characteristics of orthochromatic stock (or early panchromatic), which has a very specific spectral sensitivity. It’s blind to red, meaning skin tones often drop in brightness, and blue skies blow out easily. To honor that look, I’d be manipulating the luminance channels to replicate that specific contrast curve.

The goal is to shape the emotional weight of the image. The slums need a gritty texture mid-tones that feel heavy and dusty without crushing the shadow detail. In contrast, the moments of connection between the Tramp and Kid need a “creamy” highlight roll-off, something that feels softer and more inviting. Even without hue, we are manipulating temperature through contrast hard, high-contrast crunches for the cold, unfeeling world, and softer, lifted mid-tones for the safe haven of their home.

Technical Aspects & Tools

The Kid (1921) — Technical Specifications

| Genre | Comedy, Drama, Family, Slapstick, Fatherhood |

|---|---|

| Director | Charlie Chaplin |

| Cinematographer | Roland Totheroh |

| Editor | Charlie Chaplin |

| Time Period | 1920s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.33 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light, Hard light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Sunny |

| Story Location | California > Los Angeles |

| Filming Location | California > Los Angeles |

Stepping back to 1921, the gear was primitive but robust. The Kid was likely shot on a workhorse like the Bell & Howell 2709. This was a hand-cranked camera. That means the frame rate wasn’t a constant 24fps; it fluctuated between 16 and 20fps depending on the operator’s hand. The cameraman was essentially the rhythm section of the band.

Lighting relied on massive Carbon-arc lamps for interiors. These things were hot, loud, and spit sparks, requiring constant attention. The film stock had low sensitivity (ISO), meaning you needed a lot of light to get an exposure. The fact that Totheroh managed to get such nuanced images with equipment that was essentially a heavy box and an open flame is a testament to the ingenuity of the era.

- Also read: RAN (1985) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: DIAL M FOR MURDER (1954) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →