When I look back at a masterpiece like Buster Keaton’s The General (1926), it’s not just some academic trip down memory laneit’s a deep dive into the DNA of what we do. This film is a monumental achievement in visual storytelling that feels almost impossibly modern. It’s also a bit of a heartbreak; as the production transcripts show, Keaton’s magnum opus was a massive flop in its day. It took decades for the world to catch up to his genius. The General speaks volumes without a single line of dialogue, and honestly, it challenges those of us working today to remember how to truly see cinema.

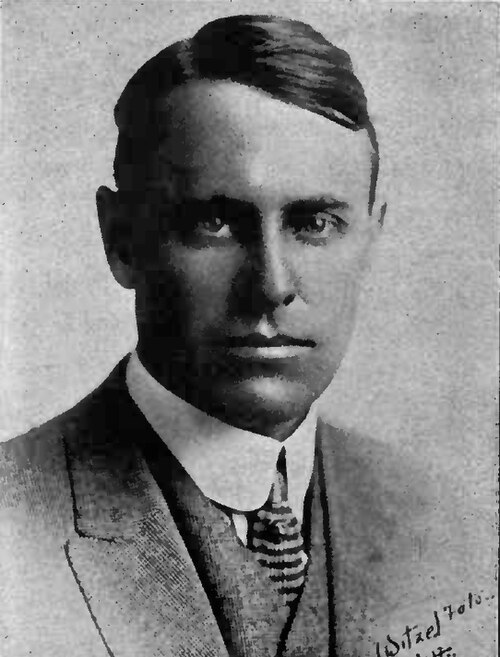

About the Cinematographer

You can’t really talk about the look of The General without talking about Buster Keaton. Sure, Bert Haines and Devereaux Jennings are the names on the tin, but Keaton was the true architect here. His “eye” didn’t come from a film school or a lighting apprenticeship; it came from the world of vaudeville.

Imagine a kid being literally thrown around a stage by his father that was Keaton’s childhood. He learned the physics of space and movement through bruises and broken bones. By the time he got behind a camera, he had this incredible “physical intelligence.” He wasn’t just an actor; he was a human special effect. He broke his neck on one set and shattered an ankle on another, but he kept going. When he looked through a viewfinder, he wasn’t just checking focus; he was mapping out a kinetic ballet. He understood depth and timing in his marrow, knowing exactly how a fall or an explosion would play out for the lens before the cameras even started cranking.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The look of The General was born from two things: Keaton’s total obsession with trains and a stubborn demand for historical truth. He’d read everything he could find on the 1862 Great Locomotive Chase. This wasn’t some “inspired by true events” fluff; Keaton wanted the real thing.

You can feel that weight in every frame. Most directors would have used miniatures or forced perspective to save a buck, but Keaton went out and bought three actual Civil War-era locomotives. It sent the budget spiraling from $400,000 to $750,000, which was an insane amount of money in 1926, but it gave the cinematography a documentary-level grit. He wanted the visceral reality of those iron beasts thundering through the landscape. The stakes a life-or-death pursuit across 87 miles demanded a visual approach that was grounded and massive. The cameras weren’t just capturing a comedy; they were capturing the mechanical poetry of the industrial age.

Camera Movements

Remember: this was an era of heavy, hand-cranked cameras and zero gimbals. Despite that, the camera work in The General is incredibly dynamic. Keaton and his DPs used movement to amplify the sense of pursuit.

The tracking shots are the standouts. They mounted cameras on flatcars or parallel vehicles to keep pace with the trains. When you see Keaton jumping between the engine and the wagons or pulling a railroad tie while the world blurs past, the risk is palpable not just for him, but for the crew trying to keep a steady frame at high speeds. The pans and tilts aren’t flashy “look at me” moves; they’re expansive. They start on the train and then pull back to reveal the scale of the Oregon wilderness or the oncoming Union forces. It creates this sense of omnipresent danger. As someone who works with digital tools, I’m still blown away by the rhythm they achieved with hand-cranks. Every move is motivated by the story.

Compositional Choices

The way Keaton composed his shots was brilliant a mix of high-stakes action and classic vaudeville “stage” logic. He constantly positioned himself as this tiny, stoic figure against the massive machinery of the trains or the giant American landscape. That contrast is where the humor and the pathos come from.

He used the railroad tracks as leading lines to pull your eye right to the horizon, making the journey feel endless. He also loved “deep staging,” which is something we’ve almost lost in modern quick-cut editing. You’ll have Keaton struggling with something on the train in the foreground, while the enemy army is visible way in the background. It gives the audience spatial awareness and builds the joke. Every frame feels meticulously crafted, using negative space and wide horizons to show just how isolated and vulnerable his character, Johnny Gray, really is.

Lighting Style

In 1926, especially for a massive outdoor shoot like this, the sun was your primary light source. The cinematographers had to be master manipulators of natural light. They used the changing position of the sun to sculpt the frame and bring out the textures of the wood and iron.

The steam sequences are a masterclass in backlighting. When that white smoke billows from the engine and the sun catches it from behind, the train feels alive almost ethereal. In black and white, contrast is everything. You need those rich shadows and bright highlights to define the form. While we use LED panels and sophisticated modifiers today, there’s a simple elegance to how they used the Oregon sun to create depth. It’s tactile. You can almost feel the heat of the engine and the coldness of the river just by looking at the tonal range of the prints.

Lensing and Blocking

Back then, you didn’t have a bag full of prime lenses or a 10:1 zoom. Lenses were slower and the options were limited to a few standard focal lengths. But those limitations forced Keaton to be a master of blocking.

Since they couldn’t rely on telephoto compression or wide-angle tricks, everything had to be choreographed with pinpoint precision. The sequence where Keaton navigates the moving train firing a cannon, dealing with water, dodging ties is a masterclass in how to move an actor through a frame. He moves from engine to tender to flatcar in these long, deliberate takes that let you track the journey in real-time. Even the famous $42,000 train wreck (one of the most expensive shots in silent film history) relied on perfect lensing. They had one shot to get it right. They chose a focal length that captured the scale of the bridge and the river, ensuring the plunge of the Texas felt as massive as it actually was.

Color Grading Approach

This is where my world as a colorist gets interesting. We didn’t have digital scopes in 1926, but the “grading” was baked into the film stock and the exposure. Decisions about dynamic range were made right there in the camera how to handle the highlights in the steam versus the shadows in the engine cab.

At the time, they also used tinting and toning to set the mood blue for night, sepia for day. If I were restoring this today at Color Culture, my job wouldn’t be to “add” color, but to honor that monochromatic palette. I’d be obsessing over the grayscale. I’d want to make sure the greens of the Oregon forests have a different tonal value than the brown earth so they don’t just turn into a muddy gray. I’d focus on the highlight roll-off in the clouds and the deep, oily blacks of the locomotive. It’s about “tonal sculpting” to make sure the film looks as sharp and impactful as it did on its first night in a theater.

Technical Aspects & Tools

The General: Technical Specifications (1.33:1 | 35mm Film)

| Genre | Action, Adventure, Civil War, Comedy, Drama, War, History, Slapstick |

| Director | Buster Keaton, Clyde Bruckman |

| Cinematographer | Bert Haines, Devereaux Jennings |

| Editor | Buster Keaton, Sherman Kell |

| Colorist | D.C. Cardinali |

| Time Period | 1800s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.33 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light |

| Story Location | Georgia > Marietta |

| Filming Location | North America > United States of America |

The technical side of The General is just staggering. No CGI, no safety nets just 200,000 feet of film and a lot of guts. Every grand spectacle you see was a real event.

The main tools were hand-cranked cameras, which required the operator to have the rhythm of a metronome. The film stocks were slow, so they needed tons of light, which is why those wide Oregon exteriors look so crisp. But the biggest “tools” were the trains themselves. Keaton didn’t just build sets; he built bridges and dams to control the water for battle scenes. The production was dangerous, too. An assistant director was shot in the face with a blank, and a train wheel ran over a brakeman’s foot. This wasn’t a cozy studio shoot; it was a gritty, mechanical, and often perilous operation that pushed the absolute limits of physical cinema.

- Also read: THE STRAIGHT STORY (1999) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: THE GRAPES OF WRATH (1940) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →