When I first encountered Julian Schnabel’s The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, it hit me with the force of a revelation. This wasn’t just a story told; it was an experience conjured. It was a total immersion into a reality I couldn’t possibly imagine, yet felt intimately. To me, it’s the ultimate example of what visual storytelling can achieve, especially when you consider that the premise is, on paper, “unfilmable.” You’re taking the memoir of Jean-Dominique Bauby a fashion editor who suffered a catastrophic stroke and was left with “locked-in syndrome” and trying to make it cinematic.

How do you make a compelling film about a man who can’t move anything but his left eyelid? The audacity of even trying is incredible. The execution? A masterclass in subjective cinematography. For me, this film is a constant touchstone when I’m discussing empathy through the lens.

About the Cinematographer

Janusz Kaminski gets the DP credit, but honestly, the cinematography here feels less like a singular “vision” and more like a fluid, deeply collaborative act of creation. Kaminski brought his seasoned eye and technical prowess, sure, but you can feel Julian Schnabel’s background as a painter in every frame.

That synergy is everything.

Mark Kermode hit the nail on the head when he admitted he didn’t go into the theater thinking Schnabel was a “great filmmaker.” But with Diving Bell, something clicked. It’s as if Schnabel was struck by lightning. The result is this wonderfully sensuous, tangible texture where the painter’s sensibility meets the cinematographer’s craft. It isn’t just about framing; it’s about how light, shadow, and color combine to create something you feel.

Even the lead, Mathieu Amalric, was modest about it, saying the camera and the light did the heavy lifting. But we also have to talk about Berthou, the cameraman. His role was incredibly intimate. Amalric mentioned that Berthou was “sometimes me” he would actually listen to the inner monologue recordings in real-time and react. If Bauby’s internal thought was “I’m bored,” Berthou would intuitively pan the camera toward a window. That’s not just technical filmmaking; it’s an organic, almost telepathic act of creation.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The real “eureka” moment actually came from the screenwriter, Ronald Harwood. He was ready to give the money back because he couldn’t figure out the script. Then he asked: “What about if the camera was Jean-Dou?”

That single idea placing the audience inside Bauby’s head became the foundation.

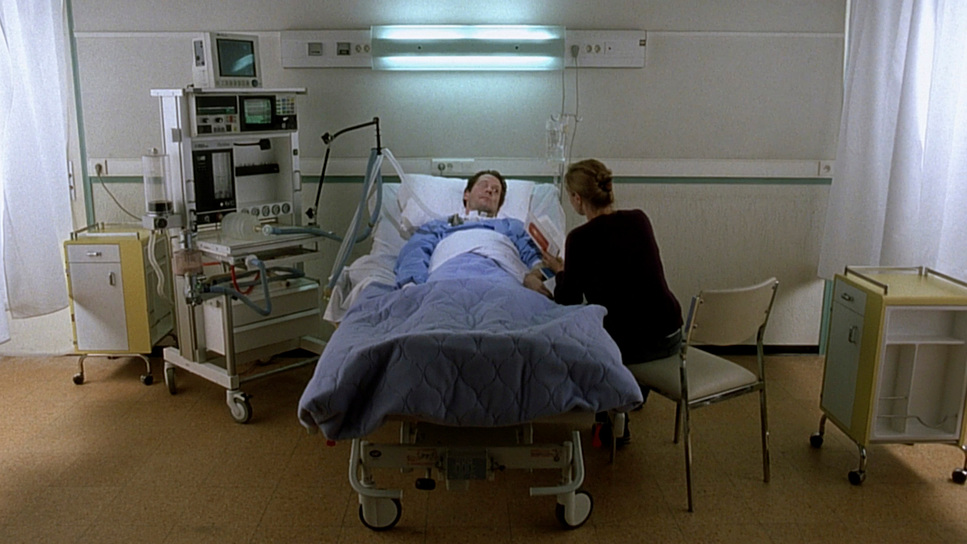

From there, Schnabel built a methodology to break every “professional” habit his crew had. They didn’t use extensive makeup to simulate paralysis or do long rehearsals. They filmed in the actual hospital in Berck-sur-Mer where Bauby was treated. They even used the same nurses and staff who had cared for him ten years prior to get the posture and movements exactly right.

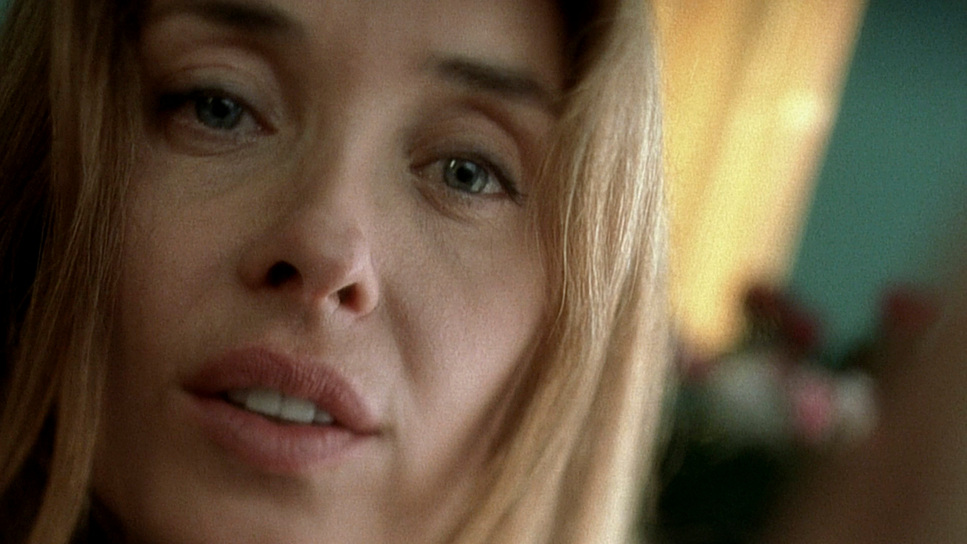

I also love that Schnabel refused to make Bauby a “saint.” He wanted to show that the man was still human still had his humor, his desires, and his “dirty thoughts.” He was still a guy looking at “the legs and the tits.” Keeping that raw, unvarnished truth in the visual approach is what makes Bauby’s interior world feel so vibrant rather than tragically purified.

Camera Movements

The camera movements are revolutionary because they are dictated entirely by Bauby’s physical limitations.

For the first act, the camera is startlingly static. We are locked in his head. Doctors loom large, blurred at the edges of the frame. The sense of claustrophobia is immediate. Visceral.

Kermode called it “terrifying,” and he’s right it evokes the dread of being buried alive. But that stillness isn’t passive. When the camera does move, those tiny pans or tilts carry immense weight because they represent the monumental effort of a man trying to shift his gaze.

As Bauby’s mind begins to escape the “diving bell,” the camera finally earns its freedom. The flashbacks are a complete relief fluid handheld shots and sweeping crane moves. I love this juxtaposition. The camera’s physical movement becomes a metaphor for his mental liberation. In his memories, the camera dances. In the hospital room, it’s tethered to a chair.

Compositional Choices

As a colorist, I’m always looking at how composition directs the eye, and Schnabel uses it here to simulate a medical condition.

Early on, we get these extreme close-ups that are warped at the edges. The world is a distorted tunnel. This isn’t just a gimmick; it’s a depth cue. Instead of using a shallow depth of field to look at something far away, they use it to isolate Bauby from everything close to him. It’s an inverted use of focus that emphasizes his confinement.

As his world opens up, the frames get some breathing room. The flashbacks are the polar opposite—bustling cityscapes and wide-open horizons. What fascinates me is the lack of negative space in the “diving bell” shots. The frames are packed with medical gear, faces, and ceilings. It’s oppressive. Then, when he finally glimpses the sky through a window, that tiny bit of sky is framed with almost religious reverence.

Lighting Style

The lighting here is a masterclass in emotional resonance. In the hospital, it’s often clinical and cool—lots of daylight and practical medical lamps. But there’s a consistent softness to it that keeps it from feeling “cheap” or flat. It has that sensuous texture Kermode mentioned; it looks like something you could reach out and touch.

Natural light is the hero here. The way the sunlight changes from dawn to dusk marks the passage of time for a man who can’t check a watch. It’s never just “bright.” It’s a specific morning glow or the diffused light of an overcast French afternoon.

From my seat at the grading panel, this is a playground. The soft highlight roll-off is beautiful; it prevents the image from feeling digital. There’s a constant interplay between the shifts in light and the emotional beats of the story. The light isn’t just illuminating the set; it’s an active participant in the narrative.

Lensing and Blocking

The technical choices here are so precise. Amalric talked about using a “Swing and Tilt” lens system, which is usually for architectural photos. It allows you to shift the plane of focus, which is how they got those incredible optical distortions of Bauby’s POV.

I find it so refreshing that this was all done in-camera. No digital “blur” filters in post-production. You can feel the physical “soul” of that Zeiss glass.

The blocking is equally brilliant. When we’re in Bauby’s POV, the actors have to interact directly with the lens. They lean in close, they look into the glass. It’s a huge challenge for an actor to show empathy to a piece of equipment instead of a human face, but it makes the immersion total for us. Then, in the flashbacks, the blocking opens up. People move freely. It’s a deliberate, painful contrast to the “glass wall” of the hospital scenes.

Color Grading Approach

If I were grading this, I’d be obsessing over the hue separation. For the hospital reality, you’re looking at a muted, cyan-heavy palette. We’re talking clinical blues, desaturated greens, and sterile grays. The goal isn’t to wash it out entirely, but to pull back the vibrancy to show life being drained away.

Contrast shaping is the key here. In those POV shots, I’d want the focus center to have a bit more “bite” while letting the blurred edges feel soft and indistinct. Because this was shot on 35mm (Vision 500T), you have this rich density in the blacks. You don’t want to “crush” them; you want them to feel tactile.

When we hit the memories, the grade should shift dramatically. I’d push for golden-hour oranges, rich reds, and lush greens. It’s about opening up the dynamic range more detail in the shadows, more sparkle in the highlights. It isn’t about being “theatrical” with the color changes; it’s about those nuanced shifts that guide the viewer’s gut feeling without them even realizing why they feel more relaxed in the flashbacks.

Technical Aspects & Tools

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly

Technical Specifications & Cinematography Data

| Genre | Drama, History, Biopic |

| Director | Julian Schnabel |

| Cinematographer | Janusz Kamiński |

| Production Designer | Michel Eric, Laurent Ott |

| Costume Designer | Olivier B |

| Editor | Juliette Welfling |

| Colorist | Gilles Granier |

| Time Period | 1990s |

| Color | Cyan |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Low contrast, Side light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Story Location | Europe > France |

| Filming Location | Europe > France |

| Camera | Arri 435 / 435ES |

| Lens | Zeiss Super Speed, Swing and Tilt Lens system |

| Film Stock / Resolution | 5279/7279 Vision 500T, 8563/8663 Eterna 250D |

The “Swing and Tilt” lens is really the star of the show. By manipulating the focus plane optically, they created a version of “impaired vision” that feels raw and authentic. Again, doing this on set rather than in a computer makes a massive difference in the final texture of the film.

The other big technical win was the simultaneous recording. Having Amalric improvise the inner monologue in another room while the camera was rolling allowed the cameraman, Berthou, to actually “hear” Bauby’s thoughts. It turned the camera into a reactive, thinking thing.

And shooting at the real hospital in Berck-sur-Mer? That’s the kind of grounded decision that yields the most profound results. You can’t fake the history of a place like that.

- Also read: PERFECT BLUE (1997) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: THREE COLORS: RED (1994) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →