When I watch The Cove, I’m looking at how cinematography is used as a weapon. It’s not just about making pretty pictures, it’s about getting the shot without getting arrested or worse.

About the Cinematographer

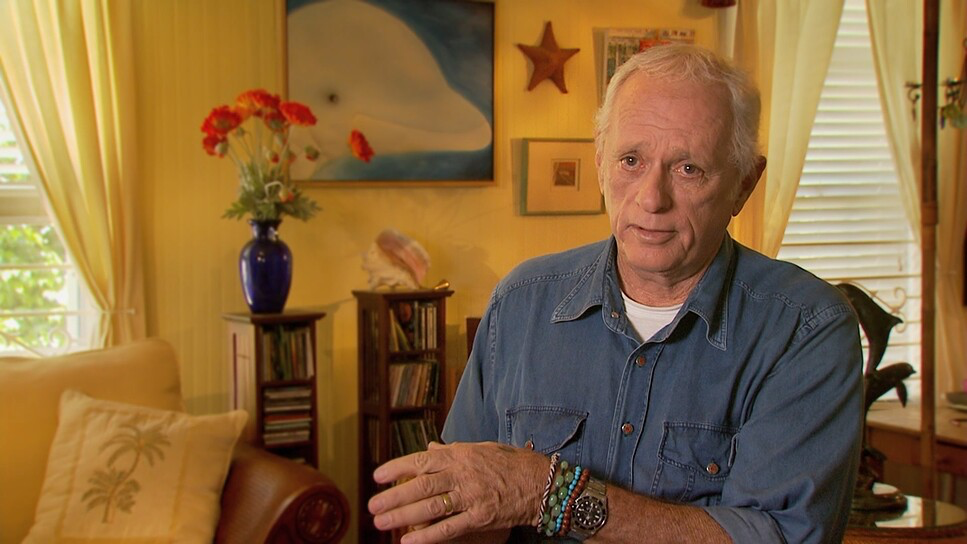

Usually, a Director of Photography (DP) is the singular vision behind a film, but The Cove required a tactical squad. You have Brook Aitken listed as the cinematographer, but it was really a collective effort involving operators like Sean B. Carroll and others. This wasn’t a standard shoot where everyone waits on the DP to check the gate.

The crew had to operate more like covert operatives than filmmakers. Consistency is usually the holy grail in our line of work, but here, the fragmentation works in their favor. You have guys holding heavy broadcast cameras one minute and free-diving with underwater housings the next. They weren’t just lensmen; they were infiltrators. The visual style isn’t polished because it couldn’t be, and that rough edge is exactly what sells the authenticity.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

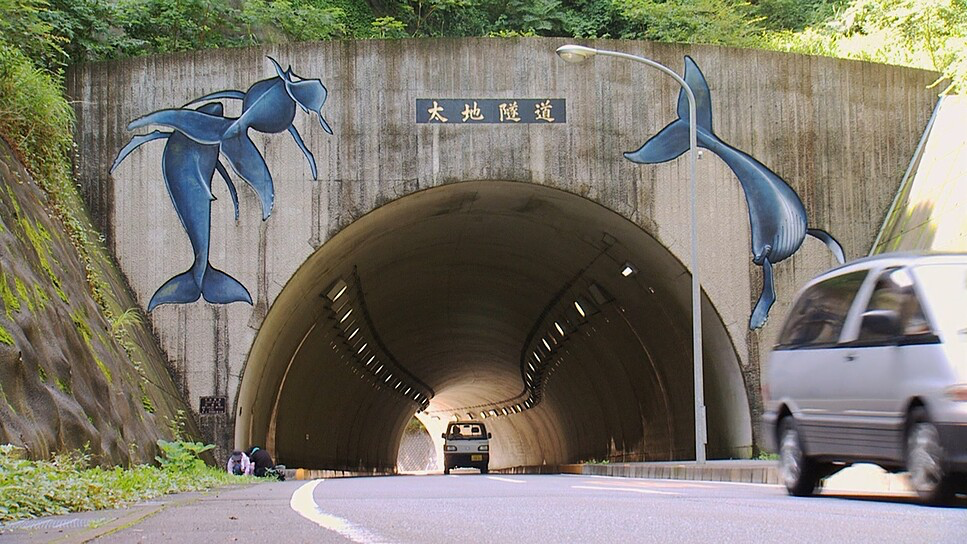

The “look” of The Cove wasn’t born from a mood board; it was dictated by paranoia. The visual instruction was simple: record the truth, don’t get caught. The narrator calls Taiji a “twilight zone,” and the visuals lean into that. You have this sunny, coastal Japanese town that looks totally benign on the surface, but the framing constantly suggests something is off.

The filmmakers were explicitly told that the fishermen would shut them down if they saw cameras. That threat dictated every focal length and camera position. This is “stealth cinematography.” The inspiration is purely journalistic—it’s the “get in, get the footage, get out” mentality. You can feel the anxiety in the shots. It’s not an aesthetic choice derived from French New Wave; it’s the aesthetic of survival.

Camera Movements

The camera movement in this film oscillates between two extremes: the shaky panic of being hunted and the cold, mechanical stillness of surveillance.

In the car scenes with Rick O’Barry, the camera is handheld, reactive, and often messy. It mimics the feeling of constantly looking over your shoulder. It’s classic vérité, but with actual stakes. Then, you cut to the hidden cameras in the cove. These shots are dead still. Locked off. No pans, no tilts, no operator breathing behind the lens. It’s chilling. This contrast is effective because it dehumanizes the footage of the slaughter. It feels like evidence presented in court objective and unblinking which makes the violence hit much harder than if a human operator were trying to follow the action.

Compositional Choices

Compositionally, this film is a lesson in shooting through the clutter. Because they were hiding, they couldn’t exactly ask the subjects to “step to the left.” They had to use dirty frames shooting through branches, rocks, and fences.

We see a lot of “natural framing” here, but not in the artistic sense. It’s functional. They are using foreground elements to hide the lens. The “Keep Out” and “Danger” signs aren’t just symbolic; they are physical barriers the lens has to punch past. This creates a voyeuristic perspective for the audience. We feel like we’re hiding in the bushes with the crew. It creates a claustrophobic visual language where the edges of the frame feel dangerous, like the walls are closing in on the subject.

Lighting Style

Lighting? There was no lighting truck on this job. This is 100% available daylight, and as a colorist, I can see the struggle in the footage. They were dealing with harsh, midday sun bouncing off the ocean, which is a nightmare for exposure.

You can see the dynamic range of the cameras being pushed to the limit. In the cove, the shadows are crushed and the highlights on the water are often clipped. But honestly? It works. If they had filled in the shadows with bounce boards or diffused the sunlight, it would have looked like a travel show. The harsh, high-contrast lighting underscores the brutality of the environment. It feels raw and unmanipulated. The lighting wasn’t “designed”; it was endured.

Lensing and Blocking

The lens choices were entirely pragmatic. For the surveillance stuff, they relied heavily on long telephoto lenses (Fujinon glass mostly), likely racking out to the extreme end of the zoom. The compression you get from those long lenses flattens the distance between the camera and the fishermen, making the danger feel closer than it actually is. It also creates that classic “paparazzi” look that screams unauthorized footage.

Blocking was non-existent in the traditional sense. You don’t block the actors; you block the camera to be invisible. They had to hide cameras inside fake rocks and foliage. The goal was to remove the “observer effect.” Usually, a documentary subject acts differently when they know a lens is on them. By removing the cameraman from the equation, they captured behavior that was completely unguarded.

Color Grading Approach

From a grading standpoint, The Cove is a “fix-it” job turned into a style. They were mixing footage from high-end Sony XDCAMs with lower-quality hidden cameras, thermal cams, and underwater footage. The color fidelity would have been all over the map.

Instead of trying to force a glossy, commercial look, the grade leans into a cool, desaturated palette, especially for the cove sequences. The fact check notes a “Cool, Blue” bias, and that’s very apparent. The ocean isn’t a tropical turquoise; it’s a cold, steel blue. As a colorist, I’d bet they spent a lot of time matching the black levels between the different cameras to make it feel cohesive. They didn’t try to hide the digital noise in the underexposed shots; they let it sit there, which adds to the gritty, investigative texture. It looks like 2000s digital video, and that dates it in the best possible way it feels like an era of raw documentation before everything got too polished.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Technically, this film is a time capsule of the transition to digital workflows. They weren’t using modern mirrorless cameras or GoPros (which weren’t really a thing yet). They were hauling around the Sony XDCAM PDW-F350. That’s a shoulder-mounted, broadcast-style camera that records onto optical discs. It’s not small, which makes the “stealth” aspect even more impressive.

For the hidden stuff, they didn’t just buy gear off the shelf. They had to engineer custom housings literally building cameras into fake rocks that matched the local geology. Integrating those industrial sensor heads with the XDCAM footage would have been a massive headache in post. They were mixing aspect ratios and frame sizes, dealing with different compression artifacts. The fact that they managed to cut it together into a film that doesn’t look like a total technical mess is a credit to the post-production team.

- Also read: HOW THE GRINCH STOLE CHRISTMAS! (1966) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: CHILDREN OF HEAVEN (1997) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →