Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) is always at the top of my list. I return to it constantly. It’s a film that is often overshadowed by the heavy hitters like Vertigo or Psycho, but to me, Rope is a quiet titan a masterclass in technical audacity that feels criminally underrated today.

On the surface, it’s a deceptively simple thriller: two men commit a murder for the intellectual “thrill” and then host a dinner party using the victim’s burial chest as a buffet table. But look beneath that macabre premise. What you’re actually seeing is a meticulous display of filmmaking prowess. Hitchcock’s bold experiment with continuous shooting forces an intimate, almost voyeuristic connection on the viewer. My obsession with Rope isn’t just about the technical “gimmicks,” though they are incredible; it’s about how every one of those choices serves the psychological rot at the core of the story.

The Eye Behind the Lens: Joseph A. Valentine

The man tasked with capturing this nightmare was Joseph A. Valentine. By 1948, Valentine was already a heavyweight, having crafted the atmospheric dread of The Wolf Man and worked with Hitchcock on Shadow of a Doubt. He had this incredible knack for using expressive lighting and deep focus to crank up narrative tension.

But Rope was a different beast entirely. It demanded a cinematographer who could move beyond the usual repertoire of flashy individual shots and instead maintain a seamless, immersive gaze over extraordinarily long takes. It wasn’t about the “money shot.” It was about the silent, sustained observation. Valentine’s quiet command of light and shadow combined with his ability to dance in tandem with Hitchcock’s rigorous blocking gave the film its technical backbone. He was the one who made one of history’s most famous cinematic experiments actually function.

The Stage-to-Screen Trap

The DNA of Rope is found in its origins as a stage play. Hitchcock famously believed that you shouldn’t “open up” a play too much when adapting it to film. Instead of expanding the setting to multiple locations, he doubled down on the claustrophobia of a single Manhattan apartment. As Steve Hayes noted, Hitchcock used camera angles to keep you trapped in that space. It wasn’t just a stylistic quirk; it was a psychological move. We are trapped in that apartment just as surely as the murderers are trapped by their own hubris.

This “one-take” gimmick was less about a technical stunt and more about drawing the viewer into the real-time unfolding of a crime. By denying the audience the comfort of a conventional cut, Hitchcock forces us to become complicit witnesses. There’s no looking away. Every set element even the furniture had to be choreographed to slide out of the way of the camera, creating a Herculean task for the crew just to maintain the illusion of real time.

The Unblinking Gaze: Camera Movements

The camera in Rope isn’t just a tool; it’s the film’s beating heart. Hitchcock and Valentine designed a fluid, balletic approach where the camera moves almost like a silent character at the party. It doesn’t flit around with omnipotent ease; instead, it dictates our focus with a dream-like persistence.

Think about the sheer physical difficulty of a ten-minute take in 1948. Every movement was a high-stakes dance: the camera glides, pans, and dollies, circling characters and pushing into suffocating close-ups. Those “invisible cuts” where the lens dives into a character’s back or a dark object to swap film reels are so subtle they preserve the tension perfectly. We can’t escape. We’re stuck in that room, feeling the pressure mount with every slow, deliberate move. It’s visual rhythm at its most stressful.

The Geometry of Murder: Compositional Choices

In a film with no edits, composition is everything. You don’t have the luxury of a quick cutaway to reset the mood. Every frame has to do the heavy lifting. Valentine and Hitchcock used the apartment’s “swanky but livable” mid-century design as a geometric canvas.

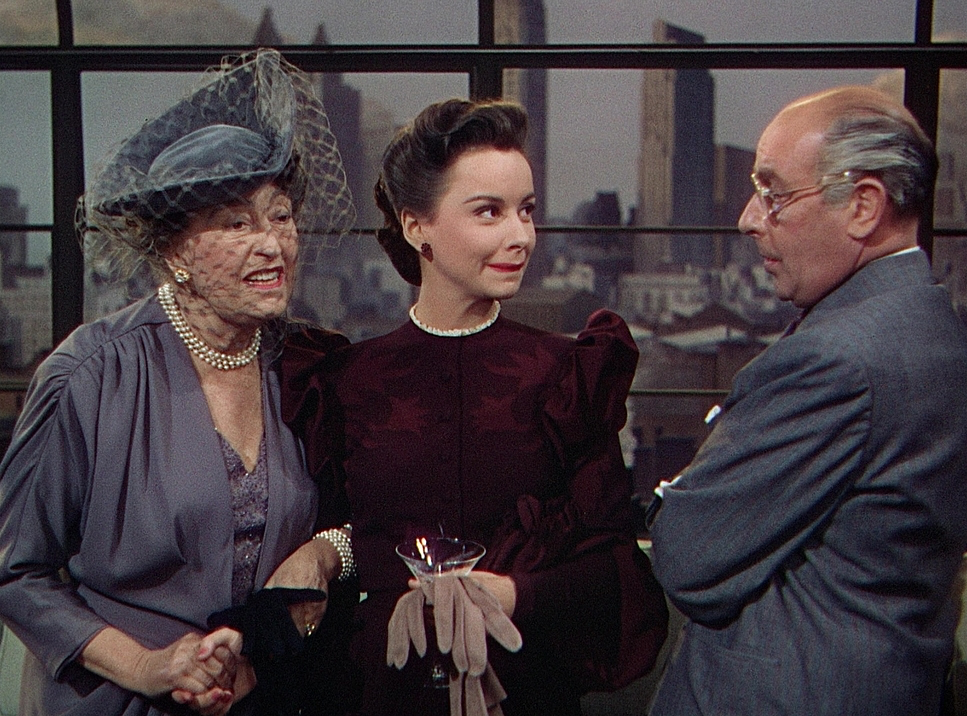

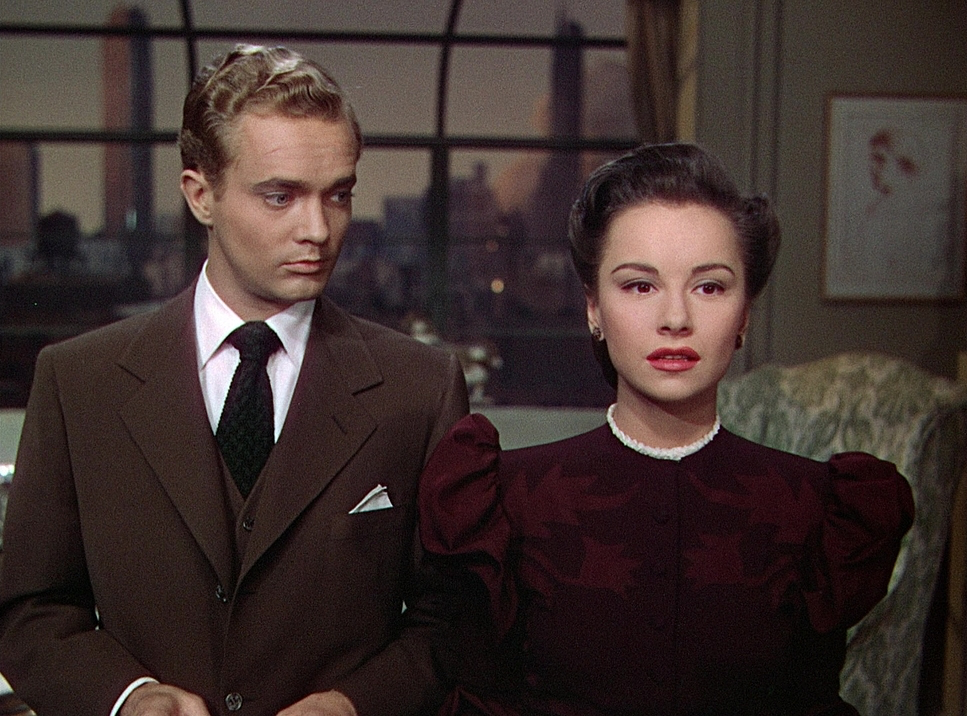

The depth of field here is remarkable. By using deep focus, they allow us to see the drama unfolding in the foreground while simultaneously tracking the movement in the background. It makes the space feel expansive yet suffocating. And then there’s the chest the silent protagonist of the film. It’s frequently tucked into the foreground or framed as an ominous shadow. Even when the characters aren’t talking about the body, the composition ensures you never forget it’s there. The wide New York skyline outside the windows serves as the ultimate contrast: a grand, indifferent world sitting just outside a room full of depravity.

Chasing the Manhattan Sunset: Lighting Style

As a colorist, the lighting in Rope is where the film really speaks to me. Hitchcock wanted a natural progression of time moving from the soft glow of a late afternoon into the oscillating neons of a Manhattan night. To get this right, they supposedly had to reshoot entire segments just to ensure the light stayed consistent.

The apartment starts bathed in warm, inviting tones. But as the sun dips and the party sours, the interior lighting becomes more pointed, letting the shadows deepen. Then the “outside” starts to bleed in. The billboards and city lights greens, reds, and whites begin to assert themselves through the glass. This transition from natural to artificial isn’t just realistic; it’s symbolic. It’s the rage and envy of the characters spilling into the room. Executing those gradual shifts during a continuous take is a feat of engineering that still boggles my mind.

The Invisible Dance: Lensing and Blocking

To make this work, Valentine had to favor wider lenses. He needed that deep focus to keep the expansive set sharp and to avoid distracting “bokeh” that might give away the transitions. The goal was transparency the lens should disappear so the audience feels unmediated immersion.

But the real magic was the blocking. This wasn’t just acting; it was an advanced form of choreography. Every step, every line of dialogue, and every camera move had to be timed to the second. The set was literally alive: furniture was on wheels, and walls were rigged to slide away silently as the camera passed. This rigorous control over the spatial relationship between the actors and the lens created a consistent visual language that defines the film’s claustrophobic power. It proves that sometimes the tightest constraints lead to the most creative storytelling.

The Technicolor Jewel Box: Color Grading

This is my wheelhouse. Rope was Hitchcock’s first foray into Technicolor, and as a colorist, I find it fascinating. Unlike my digital workflow today, the “grade” for Rope was baked into the physical medium the Three-Strip Technicolor process.

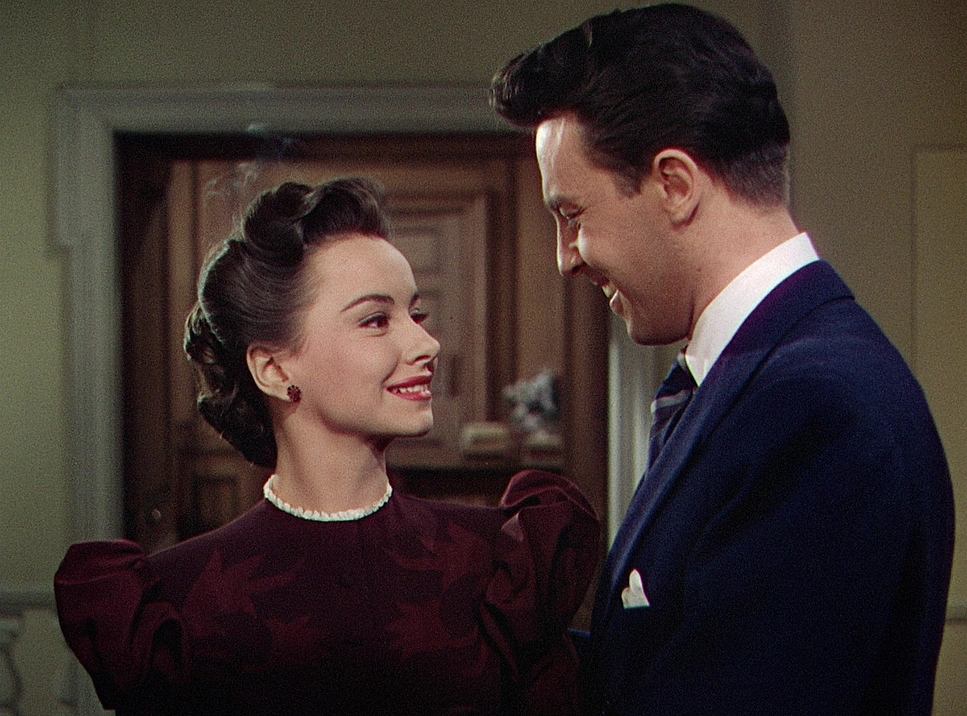

The palette is lush. You have these gorgeous emerald chairs, mahogany tables, and that red wine-colored dress. Technicolor thrived on these rich, saturated primaries. When I look at Rope, I’m seeing a level of “baked-in” intent that we often lose in modern RAW workflows. The contrast is aggressive, delivering inky blacks and punchy highlights. There’s a vibrancy that feels almost hyperreal, signaling a world of luxury that hides something monstrous. The hue separation is incredible; the colors don’t bleed or muddy, which helps define the space in that single-set environment. It’s a masterclass in how color can enhance psychological drama with operatic intensity.

The 500-Pound Behemoth: Technical Aspects

Rope (1948)

Technicolor 35mm • 1.37:1 Original Aspect Ratio

Achieving this “one-take” look required serious technical sweat. The Technicolor camera was a behemoth it required three separate rolls of film running simultaneously. Moving that giant through a crowded set while maintaining focus was an Olympic-level feat.

The entire set was an engineering marvel. Crew members were strategically placed to wheel walls and furniture in and out of frame in total silence. The “invisible cuts” were a practical necessity because the film magazines only held about ten minutes of footage. Even the New York backdrop was a complex miniature with changing skies. It was a tedious, incredibly expensive way to shoot a movie, but it cemented Rope as a daring, technologically groundbreaking experiment.

- Also read: GHOST IN THE SHELL (1995) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: A CHRISTMAS STORY (1983) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →