Some films charm you, but Roman Holiday (1953) ? It’s a warm embrace. William Wyler’s 1953 masterpiece, starring Gregory Peck and the incandescent Audrey Hepburn, is the gold standard for the “unlikely romance.” We all know the story: the escaped princess, the opportunistic reporter, and a city full of scooters. But underneath that narrative is a quiet, profound artistry in the cinematography that usually gets ignored in favor of the script. For me, this film is a masterclass. It’s proof that creative constraints like being forced to shoot in black and white on a chaotic location can actually birth something extraordinary.

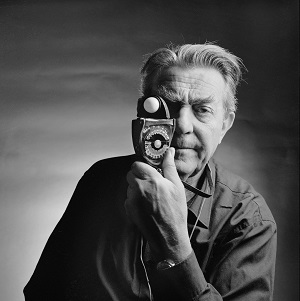

About the Cinematographer

The look of this film was a tag-team effort between Henri Alekan and Franz Planer. Alekan was the French poet of light, the guy who gave La Belle et la Bête its dreamlike texture. Planer was the versatile pro, known for a polished, high-end look that he’d later bring to Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

They weren’t just “operating” here; they were surviving. Shooting on location in Rome in the early ‘50s was a nightmare. Between the “stinking hot” heat and the fact that crowd control was basically a suggestion rather than a reality, it was chaos. But that’s where the magic happened. They took that real-world mess and turned it into cinematic authenticity. They didn’t just point a camera; they painted with the light they were given and composed with life itself.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

If you told a studio today you wanted to shoot a movie in Rome and leave the color at home, you’d be laughed out of the room. It feels counterintuitive. But for Wyler, black and white was a weapon. Paramount wanted color, but the budget was tight a million dollars in US funds were stuck in Italy and Wyler used that constraint to his advantage. He famously said, “then they’ll be watching the actors and not the scenery.”

He was spot on. When you strip away the distractions of Italian oranges and blues, you’re forced to look at the luminance of Princess Anne’s face and the shifting shadows of Joe Bradley’s conscience. The monochrome palette turns a travelogue into a fairy tale. It’s gritty because of the location, but ethereal because of the film stock. It stops being a “look at Italy” movie and starts being a “look at these souls” movie.

Camera Movements

The camera in Roman Holiday isn’t static. It breathes. It has a pulse. When Princess Anne escapes her “gilded cage,” the camera finds its own freedom. We see these fluid tracking shots where the lens is almost chasing her, trying to keep up with her sense of discovery.

Then you have the Vespa sequence. Pure energy. Even if they used extras for the hairiest stunts to protect the stars, the camera work is breathless. We’re talking quick pans, tilts, and a handheld-like energy even if they were using heavy dollies or cranes. It puts you in the seat. When Anne is trapped in the palace, the camera is formal and rigid. The moment she’s on the street, the camera becomes agile. It’s a rhythmic shift that tells the story better than the dialogue ever could.

Compositional Choices

Wyler and his DPs had a “human-first” rule for their compositions. Sure, you have the wide shots of the ruins and the piazzas, but they never let the architecture swallow the actors. Anne starts as a tiny, isolated speck in a massive palace; later, she’s a tiny, vibrant speck in a massive crowd.

The close-ups? That’s where the real work happens. The camera flat-out adores Audrey Hepburn. The tight frames capture that “naive charm” and fragility without needing a single line of script. They also mastered depth cues. You’ll often see Joe or Anne sharp in the foreground while the textured, messy life of Rome hums in the background. It keeps us anchored to their journey while making the city feel like a living, breathing participant.

Lighting Style

In my world, light is about sculpting. In black and white, it’s everything. A lot of Roman Holiday relies on that harsh, gorgeous Roman daylight. This “motivated lighting” gives the film an grit you just can’t get on a soundstage.

But look closer. When Anne is cloistered, the light is soft, almost protecting her. Once she hits the sun, the contrast kicks up. As a colorist, I’m obsessed with the “tonal range” here. The highlight roll-off how the bright Italian sun on white marble fades into mid-tones is silky. It doesn’t clip or blow out. The shadows aren’t just dead black holes; they have texture. It’s meticulous. It’s not just “pretty”; it’s emotionally resonant.

Lensing and Blocking

For the big exterior scenes, they likely stuck to wider, standard lenses. It let them capture the scale of Rome without that weird “fisheye” distortion you see in modern cheap glass. These lenses were also a bit more forgiving for blocking characters through real-world crowds.

And the blocking? It’s an art form. Wyler didn’t fight the Roman crowds; he used them. Seeing Joe and Anne weave through actual people makes the film feel like a captured moment rather than a staged play. For the intimate stuff like the “Mouth of Truth” scene the lenses get longer, the background compresses, and we’re shoved right into their personal space. Their physical dance the distance and the closeness is what builds that “great chemistry” everyone talks about.

Color Grading Approach

This is my favorite part. When I look at a black and white film, I don’t see “no color.” I see a canvas of luminance. It’s about “tonal sculpting.” Without hues to guide the eye, you have to use contrast to tell the viewer where to look.

In Roman Holiday, the grayscale is incredibly deep. I look at it and see “hue separation” through light. They made sure a blue sky and a green tree didn’t just turn into the same muddy gray; they separated them by brightness values. There’s a “print-film sensibility” here a fine grain and a natural fall-off that gives the movie a “warmth” that modern digital B&W often lacks. It proves that you don’t need a 4K color gamut to hit someone in the feelings; you just need to know how to shape the light.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Roman Holiday — Technical Specifications (1.37:1 | Black and White | 35mm)

| Genre | Comedy, Drama, Romance, Rom-Com, Adventure, Travel |

| Director | William Wyler |

| Cinematographer | Henri Alekan, Franz Planer |

| Production Designer | Hal Pereira, Walter H. Tyler, Luciano Sacripanti |

| Costume Designer | Edith Head |

| Editor | Robert Swink |

| Time Period | 1950s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.37 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, High contrast |

| Lighting Type | Moonlight |

| Story Location | Lazio > Rome |

| Filming Location | Lazio > Rome |

Shooting this in ’53 on location was a massive swing. They were likely hauling Mitchell BNCs or maybe lighter Arriflexes through crowded streets. The sheer logistics of keeping continuity while “sneaky cigarette lighter cameras” (used for the candid Irving shots) were in play is staggering.

The authenticity comes from the struggle. Using real streets instead of a backlot gave it a documentary-style edge. In the days before digital sliders, all of this tonal work happened in the lab and through optical printing. It’s a testament to the crew that, despite the analog limitations, the visual integrity never wavers.

- Also read: DOGVILLE (2003) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN (1974) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →