When I sit down with Jules Dassin’s Rififi (1955), I’m not just watching a heist movie; I’m studying a blueprint. It famously reinvented the thriller with a thirty-minute heist sequence that contains no dialogue and no music. That isn’t just a gimmick it’s a bold statement on the power of visual storytelling. It’s a reminder that when you strip away the noise, the image has to do the heavy lifting.

About the Cinematographer

To understand the look of Rififi, you have to look at the collaboration between Jules Dassin and his cinematographer, Philippe Agostini. Dassin arrived in France as a man with a point to prove. A veteran of gritty American noir, he had been blacklisted in Hollywood during the McCarthy era a “career death sentence” that forced him into exile.

Agostini was the perfect partner for this transition. Unlike the polished, high-glamour look of Hollywood at the time, Agostini brought a quintessentially European sensibility to the 35mm frame. Together, they channeled Dassin’s frustration and “outsider” status into a visual style that felt raw and urgent. They weren’t just making a movie; they were stripping noir down to its bare, cynical bones.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The DNA of Rififi is rooted in two things: Dassin’s noir background and a relentless drive for hyper-realism. Dassin didn’t want a “movie” robbery; he wanted a procedural. This meant the cinematography had to be observational rather than sensational.

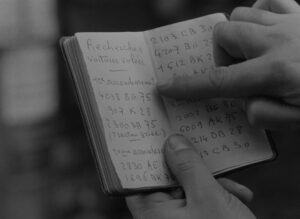

The core philosophy here was “show, don’t tell.” Because Dassin committed to a silent heist, the camera had to explain the mechanics of the crime the “modishing” of police movements, the entry into the back office, the physics of drilling into a safe. As a filmmaker, I find this fascinating because it forces the audience into a state of complicity. You aren’t just watching a gang; you’re practically holding the flashlight for them.

Camera Movements

What strikes me most about the pacing is Dassin’s restraint. In modern thrillers, we’re used to rapid-fire editing to create “excitement.” Dassin does the opposite. He favors long, deliberate tracking shots that move with the characters.

Instead of cutting away to hide the “boring” parts, the camera glides through the space, maintaining the tension in real-time. By opting to move the camera rather than cut, Dassin preserves the “lived-in” experience of the heist. We see the agonizing slowness of their work. Every slow pan or subtle track makes the audience feel the physical weight of the tools and the claustrophobia of the room. It’s a masterclass in using movement to control the viewer’s pulse.

Compositional Choices

Working within the 1.37:1 aspect ratio, Dassin and Agostini had to be incredibly precise with their framing. In that nearly square box, every element matters. They used a lot of “voyeuristic” compositions like the iconic shot looking down through the hole in the ceiling which places the viewer in a position of both power and vulnerability.

One of the smartest compositional anchors is the recurring clock. Whether it’s sitting in the corner of a wide shot or framed in a tight close-up as a character lowers his wrist, that clock is the film’s heartbeat. Dassin doesn’t need a ticking sound effect; he uses the visual repetition of the clock face to externalize the pressure. It’s elegant, visual shorthand that keeps us “in the moment” without a single word of exposition.

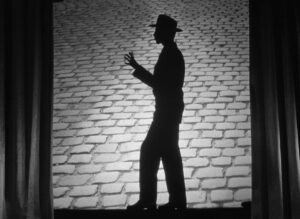

Lighting Style

This is where the film’s Noir heart really beats. The lighting is unapologetically hard and high-contrast. Shot mostly in interior locations and basements, Agostini utilized hard top-lighting that carves out the actors’ features.

As a colorist, I love how they used “motivated” light sources. When the power is cut, the scene relies on the harsh, directional beams of torches and bare bulbs. This creates deep pockets of “true black” where danger hides. The shadows aren’t just empty space; they are sculpted elements of the set. The interplay of light catching the dust in the air or reflecting off a drill bit adds a layer of grit that feels tangible. It’s not about making the actors look “good” it’s about making the situation feel dangerous.

Lensing and Blocking

For most of the heist, Dassin sticks to medium lenses and two-shots, which keep the spatial relationships clear. You always know where the characters are in relation to the safe and the door. The blocking is almost like choreography; it’s a dance of precision.

The gang moves with a practiced, methodical rhythm, and the camera follows that lead. Often, the blocking leads the camera rather than the camera dictating the movement. By keeping the lensing “natural” (avoiding extreme wide-angle distortion), the film maintains its documentary-like feel. We see the strain on their faces and the sweat on their brows through careful close-ups that feel earned, not forced.

Color Grading Approach

If I were sitting at my DaVinci Resolve panel today to remaster Rififi, I wouldn’t touch a thing about its monochromatic intent. Instead, I’d focus on tonal sculpting.

My goal would be to honor that 1950s silver-halide look. I’d focus on the highlight roll-off making sure those bright torch lights have a soft, filmic glow rather than a harsh digital clip. I’d ensure the black levels are robust but not “crushed,” keeping just enough detail in the shadows of that Paris basement to maintain the depth. Modern HDR gives us the tools to make these mid-century blacks feel incredibly rich, and I’d want to preserve the natural grain of the 35mm stock. It’s about bringing out the soul of the celluloid, making the image feel vibrant and “wet” even in black and white.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Rififi (1955) — 35mm, 1.37:1 B&W

| Genre | Action, Crime, Drama, Heist, Film Noir, Thriller |

| Director | Jules Dassin |

| Cinematographer | Philippe Agostini, Raymond Pierre Lemoigne |

| Production Designer | Auguste Capelier, Alexandre Trauner |

| Costume Designer | Rosine Delamare |

| Editor | Roger Dwyre |

| Time Period | 1950s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.37 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, Top light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light |

| Story Location | France > Paris |

| Filming Location | France > Paris |

Shooting on 35mm in 1955 meant Dassin was working with heavy, bulky equipment. Achieving those fluid tracking shots wasn’t as simple as putting a camera on a gimbal; it required incredible skill from the dolly grips and meticulous planning.

They didn’t have the luxury of high ISOs or digital previews. The “tricks” like the superimpositions of the clock had to be handled through optical printing or in-camera. Knowing that the silent heist wasn’t even in the original script makes the technical execution even more impressive. It shows that Dassin’s intuition for visual narrative was stronger than any technical limitation of the era. He used what he had hard lights, 35mm film, and a basement to create something that still feels modern seventy years later.

Rififi (1955) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from Rififi (1955). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: 13TH (2016) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: THEY SHALL NOT GROW OLD (2018) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →