Rain Man isn’t the film you reference for flashy, groundbreaking VFX or wild camera moves. It doesn’t try to dazzle you like the blockbusters of the late 80s. Instead, John Seale’s work on Barry Levinson’s 1988 film is a lesson in subservience placing the cinematography entirely at the service of the characters.

It is, at its heart, a road movie, but the visual language is distinct. It avoids the romanticized, golden-hour gloss typical of the genre. Instead, it leans into something more observational and grounded. When I revisit this film, I’m struck by the visual grammar used to separate Tom Cruise’s Charlie the fast-talking, “iconic 80s yuppie” from Raymond’s rigid, internal world. The camera doesn’t just record them; it acts as the bridge between two completely incompatible perspectives.

About the Cinematographer

The man behind the lens was the legendary Australian cinematographer John Seale (ACS, ASC). Most people today know him for the high-octane visual assault of Mad Max: Fury Road, or the sweeping grandeur of The English Patient. But looking back at his 80s work, specifically here and in Peter Weir’s Witness, you see a different beast.

Seale is a practical filmmaker he started as a camera operator, and it shows. He has an innate ability to be in the right place without disrupting the actors. For a dialogue-heavy film like Rain Man, where the chemistry between Hoffman and Cruise is the only special effect, Seale’s unobtrusive style was critical. He knew when to light a scene to perfection and when to step back and let the natural chaos of a location dictate the frame.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The visual approach directly mirrors the narrative structure: a collision between the artificial and the organic. We start in Charlie’s world Los Angeles. It’s smoggy, industrial, and framed with rigid geometry. The opening shots, featuring the Lamborghini being crane-lifted against that hazy LA backdrop, establish a world of superficial value and high contrast.

As the story shifts to the road, the inspiration changes to capture the “unvarnished” American landscape. The metadata of the film tells us they moved from Melbourne to Wallbrook, covering vast stretches of highway. Seale stripped away the gloss. The cinematography becomes observational, almost documentary-like in its patience. The visual arc is clear: we move from the cluttered, controlled environments of Charlie’s business to the open, unpredictable horizons of the road trip. The camera stops chasing Charlie and starts waiting for Raymond.

Camera Movements

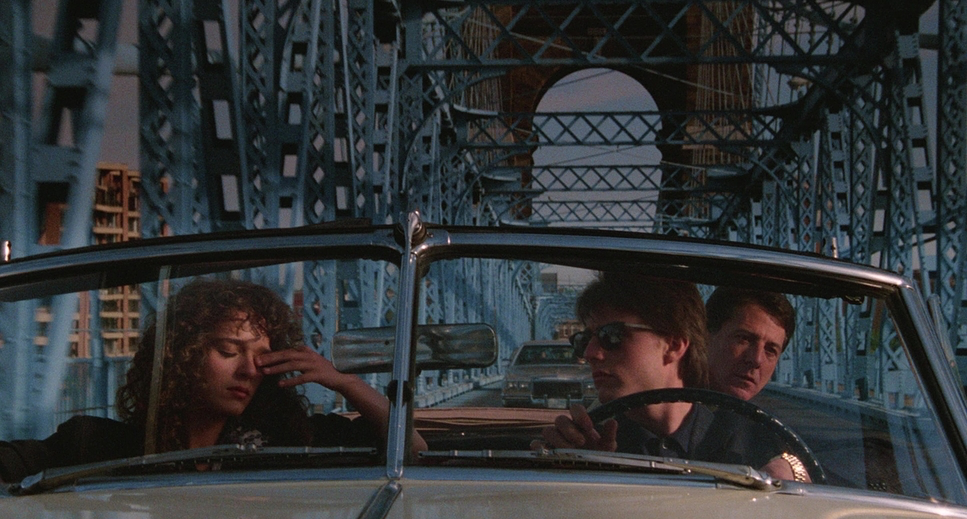

Camera movement in Rain Man is rarely used for style points; it’s strictly motivated by character psychology. We see a lot of static frames, which effectively ground Raymond’s need for routine and stasis. When the camera does move, it’s usually tracking the car a Buick Roadmaster gliding across the landscape.

Technically, shooting inside a car in the 80s was a nightmare compared to today. The “movements” inside the vehicle are claustrophobic. Seale often uses a simple push-in during moments of realization, but he resists the urge to over-cover the scene. Conversely, we see the use of steady, wide shots to emphasize Raymond’s isolation. There’s a specific discipline in holding a shot while a character walks a precise, neurotic path in the background. It emphasizes that while Charlie is living in a fast-paced drama, Raymond is living in a repetitive loop.

Compositional Choices

The film was shot in spherical 1.85:1, not anamorphic widescreen. This was a smart choice. Anamorphic might have made the film feel too epic or romantic; the 1.85 aspect ratio keeps it grounded and heightens the actors in the frame.

Compositionally, this film is a study in the “Two-Shot.” Early in the film, the framing emphasizes the distance between the brothers. They are often placed at opposite edges of the frame, with negative space or physical barriers between them. As the journey progresses, the focal lengths get longer, compressing the background and visually forcing them together. By the time we hit the third act, the framing has tightened. They share the center of the screen. Seale also uses deep focus effectively in exterior shots, keeping the environment sharp to remind us of the vast, indifferent world they are traversing, while using shallow depth of field in the car to isolate them in their own private bubble.

Lighting Style

The lighting is what I’d call “80s Hard/Natural.” Unlike the giant soft sources we use today (like 12×12 diffusion frames), the lighting in Rain Man has a bit more bite. It hits the actors directly. Seale utilizes hard light to mimic the harsh sun of the open road, creating strong shadows that define the actors’ faces.

Interiors are handled with a mix of practicals and motivated key lights. However, the Las Vegas sequence is the outlier. Here, the lighting shifts to reflect the artificiality of the casino mixed color temperatures, neon greens, and tungsten warmth clashing together. It creates a disorienting, saturated environment that contrasts sharply with the flat, dusty light of the road. It’s worth noting that they were shooting on film stocks that loved contrast; the highlights on the casino lights bloom and roll off in a way that digital sensors still struggle to replicate perfectly.

Lensing and Blocking

According to production notes, Seale leaned heavily on long lenses (telephoto) for much of the road trip. A long lens does two things: it compresses the background (making the road behind them feel like it’s right on top of them) and it flatters the faces. Using Panavision glass, likely in the 85mm to 135mm range for close-ups, allows the audience to feel intimate with the characters without the distortion of a wide angle.

The blocking is just as technical. Charlie is blocked to be dominant he stands over Raymond, he paces, he invades space. Raymond is blocked to be static, often looking away from the person speaking to him. The camera placement respects this. Seale often frames Raymond in profile or from a slightly high angle, emphasizing his vulnerability. The evolution of the blocking from Charlie towering over Raymond to sitting beside him at eye level tells the story of their relationship better than the dialogue does.

Color Grading Approach

From a colorist’s perspective, Rain Man is fascinating because it relies on the inherent characteristics of the film stock rather than digital manipulation. It was likely shot on Kodak 5294 (a high-speed 400T stock popular in the 80s). This stock had a distinct grain structure and a natural warmth.

The “grade” (or the timing, as it was back then) respects the natural palette. We see a lot of warmth in the skin tones and a general earthy quality to the exteriors. There is a distinct greenish cast in some of the motel interiors and car scenes likely a combination of uncorrected fluorescent tubes and the tint of the car glass. In modern grading, we might be tempted to “clean that up,” but leaving those murky greens contributes to the gritty, exhausted feel of the road trip. The saturation is rich but not digital; reds (like the car or the fonts in the casino) pop, but the shadows retain a thick, filmic density that anchors the image.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Rain Man: Technical Specs

| Genre | Drama, Road Trip, Political, Buddy, Comedy, Melodrama |

| Director | Barry Levinson |

| Cinematographer | John Seale |

| Production Designer | Ida Random |

| Costume Designer | Bernie Pollack |

| Editor | Stu Linder |

| Time Period | 1980s |

| Color | Warm, Saturated, Green |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.85 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Story Location | … Melbourne > Wallbrook |

| Filming Location | … Melbourne > St. Anne’s Convent |

| Camera | Panavision Panaflex |

| Film Stock / Resolution | 5294/7294 EXR 400T |

In 1988, the toolkit was analog and mechanical. Using the Panavision Panaflex Gold (the workhorse of that era), the team had to rely on light meters and intuition. There were no calibrated monitors on set to check exposure.

Shooting on 35mm film (specifically the 5294 stock) meant managing grain in low light. The 400T stock allowed them to shoot in lower light conditions like the car interiors or the evening scenes without massive lighting setups, but it introduced a texture that adds grit to the image.

We also have to mention the audio-visual sync. Hans Zimmer’s score a breakthrough use of the Fairlight CMI synthesizer works in tandem with the visuals. The rhythmic, electronic pulse matches the turning wheels of the Buick and the repetitive nature of Raymond’s mind. It’s a rare instance where the score and the camera movement feel locked in a mechanical embrace.

- Also read: ZOOTOPIA (2016) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: THE PURSUIT OF HAPPYNESS (2006) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →