Some movies speak a visual language that survives long after the dialogue fades, and honestly, few do it with the raw, gut-punch power of Franklin J. Schaffner’s Papillon (1973). It’s a film that has lived in the back of my mind for years not just for the McQueen/Hoffman powerhouse duo, but for its uncompromising, almost brutal visual storytelling.

Looking back at it now, fifty years later, the cinematography is still a masterclass in how to evoke mood and scale. It’s a beautiful film, but in a jagged, painful way. For anyone working in post-production or behind a lens, delving into its construction reveals layers of craft that feel incredibly modern despite the 1973 timestamp. It’s a testament to how specific, bold visual choices can carry the weight of a story about the breaking of the human spirit.

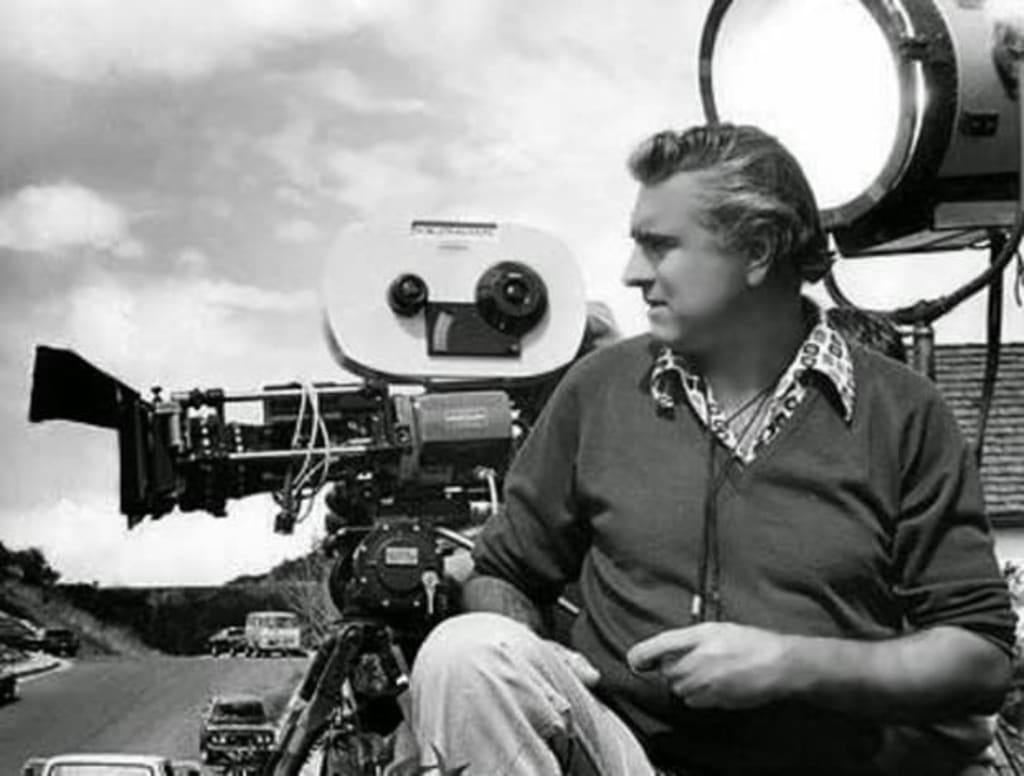

About the Cinematographer

The eyes behind this journey belonged to Fred J. Koenekamp, ASC. Now, Schaffner had previously worked with the legendary Ernest Laszlo on Patton, but Koenekamp brought a different kind of “dirt under the fingernails” sensibility to Papillon. His work here is robust and unapologetically naturalistic a perfect marriage for the unglamorous, humid settings of a penal colony.

Koenekamp wasn’t interested in “pretty” for the sake of it. He served the story with a kind of emotional clarity that I really admire. If you look at his filmography, he had this incredible knack for balancing the epic scope of a landscape with the claustrophobic intimacy of a character’s internal struggle.

Shooting this was, frankly, a logistical nightmare. They were bouncing between Spain, Jamaica, and Hawaii long before the era of “fixing it in post” or green screens. This was about dragging a crew into the mud to capture the physicality of Charrière’s world. To maintain a consistent visual grammar while battling the harsh sun and humidity of these disparate locations and making it all look like one cohesive nightmare is a feat of technical endurance that most modern productions would struggle to replicate.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The foundation here is Henri Charrière’s 1969 autobiography. Whether or not every detail of his escape from French Guiana was “true” is almost beside the point; the feeling of the book was gritty and hopeless, and the film had to match that beat for beat.

Schaffner clearly wanted a visual style that grounded the more “tall tale” elements of the story in a believable, oppressive reality. You see that in the production design the Falmouth, Jamaica prison set was over 800 feet long, built from original blueprints. Charrière himself supposedly walked onto that set and was floored by the authenticity. That dedication to “real” space meant the camera didn’t have to pretend; it could just observe the brutality. The lens became a silent witness to the erosion of dignity. Every choice, from the jungle density to the open ocean, was designed to show us the passage of time rather than just tell us about it.

Camera Movements

The movement in Papillon is all about the contrast between confinement and the dream of liberation. Inside the prison walls, Koenekamp keeps things heavy. The camera is often static or moves with a slow, deliberate dread. It lets the architecture and the sweat on the actors’ faces fill the frame. Even when there’s a crowd, like the 600 German farmers playing prisoners or the massive 1,000-person arrival scene, the camera doesn’t feel “free.” It feels like it’s documenting a system.

But the moment an escape begins? The energy shifts. Suddenly, we see these expansive, fluid tracking shots. There’s a sequence of McQueen tearing through the foliage where the camera trails him, swaying just enough to feel like we’re running alongside him. These dynamic moments offer the audience a hit of adrenaline, which only makes the abrupt, jarring halts when an escape fails feel even more devastating.

Then, of course, there’s the Maui cliff jump. McQueen doing that stunt himself is legendary, but the camera work sells the stakes. They used wide, sweeping crane shots (and potentially helicopter mounts, which were a massive undertaking then) to capture the sheer scale of that plunge. It’s one of the few moments where the camera truly “breathes,” capturing a sense of personal freedom that feels earned.

Compositional Choices

This is where the film really speaks to me. Koenekamp uses negative space like a weapon. During the solitary confinement sequences, you’ll see McQueen framed as this tiny, fragile figure dwarfed by massive, indifferent walls. It makes the isolation feel physical. You don’t just see his loneliness; you feel the “weight” of the empty space around him.

He saves the tight close-ups for the breaking points. We get uncomfortably close to the characters, watching the light leave their eyes. In solitary, the frame is often just a sliver of a face emerging from the dark. Contrast that with the wide shots of the 800-foot prison complex or the endless ocean. By placing these vulnerable human beings against these monumental backdrops, the composition constantly reminds you that the “house always wins.”

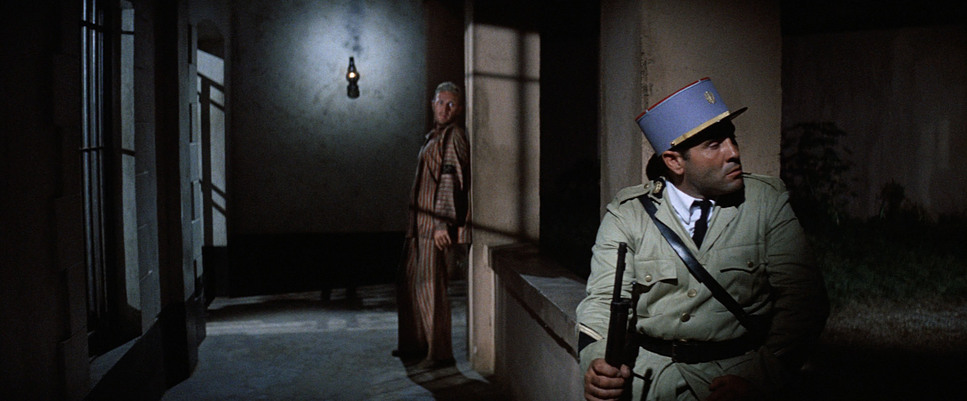

There’s also some brilliant depth cues happening in the hallways. The way lines converge toward distant watchtowers creates this visual funnel. It makes the prison feel like a geometric impossibility as if the building itself is designed to make escape look like a fantasy.

Lighting Style

As a colorist, I could talk about the lighting in this film for hours. It’s easily the most potent storytelling tool in the kit. Koenekamp leaned into a high-contrast, naturalistic look. The tropical sun isn’t romanticized; it’s rendered with a harsh, unforgiving intensity. It’s the kind of light that makes you want to squint.

The solitary scenes are the highlight for me. Koenekamp used minimal, motivated light sources maybe a single shaft of light from a high vent. He was sculpting with darkness. It wasn’t just underexposure; it was about using the “absence” of light to convey sensory deprivation. As the years pass in the story, the subtle shifts in that light are the only things that mark the time. It’s raw, authentic, and incredibly disciplined.

Lensing and Blocking

The lensing feels like a deliberate tug-of-war. Wide-angle lenses established the dehumanizing scale of the system, making the lines of convicts look like part of a machine. But then, Koenekamp would switch to longer focal lengths(telephoto) to compress the space and isolate the performances. When Papillon and Dega are whispering in the yard, the long lens pulls us into their confidence while blurring the world around them, creating a tiny pocket of humanity in a brutal place.

The blocking how the actors move in relation to each other is just as vital. McQueen’s Papillon is all restless, kinetic energy, while Hoffman’s Dega is more contained and cerebral. The way they occupy the frame together changes as their bond evolves from a “deal” to a brotherhood.

And I have to mention the butterflies those 2,500 imported blue morphos. The lenses capture them with a macro-like intimacy that provides the only “pop” of surreal beauty in the entire film. It’s a brief, calculated break from the grit.

Color Grading Approach

Looking at Papillon from a colorist’s desk, you have to respect the photochemical restraint. There were no digital power windows or hue qualifiers in 1973. This look was “baked in” through film stock choice and timing in the lab.

The palette is beautifully desaturated. It’s all earthy ochres, muted jungle greens, and dusty grays. It feels “lived-in.” As a colorist, I’m obsessed with the highlight roll-off here. On modern digital sensors, bright skies often “clip” and look plastic, but here, the sun on the prison stone has a soft, organic graduation that only 35mm provides. The contrast shaping is aggressive but retains detail in the “inky” blacks of the cells.

When we do get color like those blue butterflies or the skin tones in the native village it feels like a drink of water in a desert. The hue separation is subtle; the blues of the ocean stay deep and “film-like,” never veering into that artificial teal we see too much of today. It’s a masterclass in letting the texture of the grain define the emotional temperature.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Papillon (1973) — Technical Specifications

| Genre | Crime, Drama |

| Director | Franklin J. Schaffner |

| Cinematographer | Fred J. Koenekamp |

| Production Designer | Anthony Masters |

| Costume Designer | Anthony Powell |

| Editor | Robert Swink |

| Time Period | 1930s |

| Color | Cool, Desaturated |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.39 – Anamorphic |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Filming Location | North America > Jamaica |

| Camera | Panavision Cameras |

| Lens | Panavision Lenses |

Under the hood, Papillon was a 35mm Panavision show. These were the workhorse cameras of the 70s heavy, reliable, and capable of surviving the Jamaican humidity. The lack of CGI meant the production had to lean on sheer scale.

The $12 million budget (huge for the time) didn’t go to pixels; it went to those 600 German farmer extras, the 2,500 butterflies, and the massive physical sets. Even the lighting was a logistical “fun time” hauling massive tungsten units and early HIDs into remote locations without reliable power. The fact that the production supposedly lost $30,000 in costumes and props to locals after they wrapped tells you exactly how “out there” they were.

- Also read: STALKER (1979) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: ROMAN HOLIDAY (1953) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →