Federico Fellini’s 1957 masterpiece Nights of Cabiria don’t just leave an impression; they haunt you. It’s a film that looks simple on the surface but is actually a profound masterclass in how visual choices elevate a gritty narrative into something mythic. Every time I revisit it, I’m not just watching for the emotional gut-punch; I’m looking at the sheer, brilliant logic of the cinematography.

Color Grading Approach

Starting here might seem odd for a black-and-white film from 1957, but for a colorist, “grading” is just tonal management. Back then, this was all lab-based alchemy manipulating exposure during printing and choosing specific stocks to sculpt the image.

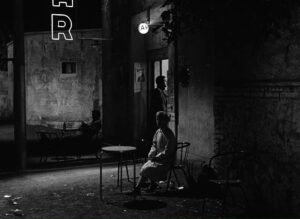

When I look at Cabiria, I see a conscious effort to build a nuanced tonal palette that handles the transition from Rome’s impoverished outskirts to Cabiria’s internal “color.” If I were grading this today, I’d be obsessed with the highlight roll-off. Notice how the light reflects off the wet streets or hits Giulietta Masina’s face; the whites are creamy and organic, never “clipped” or digital-feeling. There is a “print-film density” in the blacks that gives the image a tactile, heavy quality. It’s about leveraging the expressive power of contrast to direct the eye shaping the grays so that Cabiria feels like a vibrant burst of energy even in a monochromatic world.

Lighting Style

In black and white, lighting is your only tool for depth, and Martelli (and Tonti) used it to create a world that feels both impoverished and strangely beautiful. The lighting here is where the “sad clown” archetype really comes to life.

The contrast is often robust think of the harsh, unforgiving sun on the riverbanks or the gritty shadows of the Roman night. But then, look at the magic show scene. The lighting shifts to something more ethereal, almost motivated by her own hope. My favorite detail? That single, deliberate “black tear” in the final sequence. The way the light catches Masina’s expressive features, highlighting her clown-like eyebrows and that smudge of mascara, is incredibly intentional. It captures the performance she puts on for the world while laying her raw vulnerability bare.

About the Cinematographers

The visual architecture of Nights of Cabiria was primarily the work of Otello Martelli, a long-time Fellini collaborator, with additional work by Aldo Tonti. Martelli wasn’t just a technician; he was a craftsman who had to translate Fellini’s internal, dreamlike landscapes into tangible negatives.

At this point in 1957, Fellini was restless. He was moving away from the rigid “rules” of Italian neorealism and dabbling in the surrealism that would later define 8½. Martelli and Tonti had the difficult job of anchoring those budding artistic aspirations. They kept the world grounded and “real” (post-war grit), while slowly introducing the dreamlike, circus-inspired textures that Fellini was starting to crave. It’s a perfect visual bridge between two eras of cinema history.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The film sits at a fascinating crossroads. On one hand, you have the “darker, impoverished world” typical of post-war Italian neorealism working-class characters and raw locations. On the other, you have Cabiria herself.

Giulietta Masina’s performance is eccentric, passionate, and almost cartoonish. She’s essentially a character born of fantasy dropped into a very grim reality. The cinematography has to balance this dichotomy. It needs to show us the desolate riverbanks and lonely apartments without snuffing out Cabiria’s theatrical spirit. The visual language treats her as “color” in a black-and-white world, highlighting her internal luminescence against the monochromatic, often indifferent, backdrop of Rome.

Camera Movements

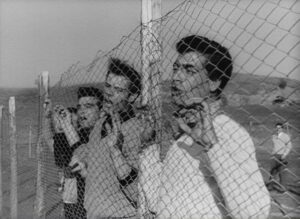

The camera in Nights of Cabiria acts like an empathetic, silent companion. Take the opening: we start with extreme long shots of Cabiria before the camera patiently moves in. That initial distance is brutal; it makes the moment her lover pushes her into the river feel even more shocking because she looks so small and vulnerable against the landscape.

Throughout the film, the tracking shots follow her through the streets with a certain fluidity. The camera doesn’t judge; it just observes her frantic energy. In the magic show scene, the camera’s “dance” physically reveals her inner truth to the audience while she remains oblivious. It’s a subtle way of creating depth cues that reinforce her emotional journey without being heavy-handed.

Compositional Choices

Martelli’s framing is designed to scream “isolation.” He constantly places Cabiria as a tiny, determined figure against massive backdrops grand mansions or indifferent crowds. This use of negative space visually articulates her status as the ultimate outsider, the drifter that society ignores.

Even when she’s in a place of opulence, like the movie director’s house, the composition emphasizes her humbleness. Yet, she never gives up her personality. The framing respects that. I love how the film uses circular structures Cabiria often ends up back on the same street corners. The unchanging backdrops highlight the fact that while she transforms inwardly, her world remains stubbornly the same. It’s a precise balance of grandeur and intimacy.

Lensing and Blocking

For the most part, the lensing stays naturalistic. They likely leaned on wide and medium lenses to keep the depth of field deep, ensuring Cabiria stayed rooted in her environment. When we do get closer, the shift feels earned it isolates her from the background just enough to feel intimate without losing the “neorealist” grit.

The blocking is where the theatricality shines. Cabiria’s movements are goofy, comical, and almost Chaplin-esque. Even in a crowded church, she’s blocked to stand apart. Her physicality is her armor. Think about the magic show again: she is placed front and center, under a hypnotic spotlight, which literally and figuratively stages her emotional vulnerability for everyone to see.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Nights of Cabiria: 1.37:1 | Black & White | 35mm

| Genre | Drama, Melodrama |

| Director | Federico Fellini |

| Cinematographer | Otello Martelli, Aldo Tonti |

| Production Designer | Piero Gherardi |

| Costume Designer | Piero Gherardi |

| Editor | Leo Catozzo |

| Time Period | 1950s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.37 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light, Side light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light, Practical light |

| Story Location | Lazio > Rome |

| Filming Location | Lazio > Rome |

Shooting on 35mm in 1957 meant dealing with robust but rigid tools. They were likely using Kodak Double-X, a medium-speed stock that provided that beautiful, characteristic grain. The cameras likely workhorses like the Arriflex 35 II or Mitchell BNC had to be handled with precision to pull off those smooth tracking shots.

Lighting was a different beast then. They were using massive carbon arc lamps for exteriors, which meant every setup was a major production. You couldn’t just “run and gun.” The limited dynamic range of the film stock required perfect exposure to hold detail in both the deep shadows and the bright Italian sun. That’s why the image feels so “intentional” every highlight and shadow was a hard-fought battle of craft.

Nights of Cabiria (1957) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from Nights of Cabiria (1957). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: PAPER MOON (1973) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: DEPARTURES (2008) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →