Few films animated or otherwise dive into the human psyche with such brutal honesty and visual daring. It’s a masterclass in using every tool in the kit to articulate internal states, cosmic dread, and the very messy business of what it means to connect. Or, more accurately, the agony of failing to. Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion (1997) isn’t just a movie, it’s a visceral punch to the gut. If you’re obsessed with how images make us feel, this is the goldmine.

About the Cinematographer

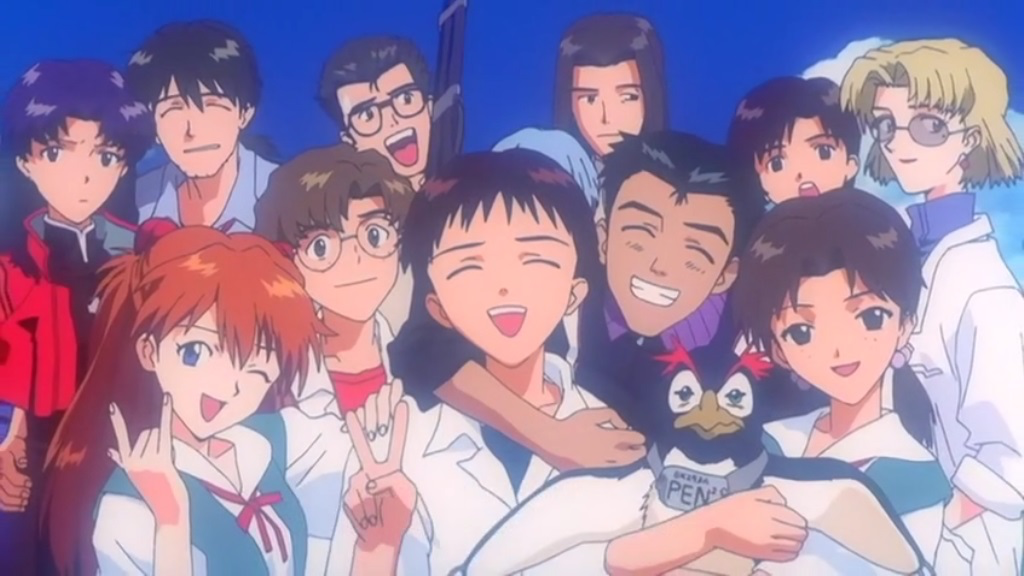

When we talk about “cinematography” in animation, the rules change. There’s no DP on a physical set adjusting a tripod, but there is a master of light and composition. In Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion, that master was Hisao Shirai. While the film is unequivocally driven by Hideaki Anno’s psychological state, it was Shirai’s technical brilliance in photography and compositing that translated those fever dreams into a cohesive visual language.

This film was born from a place of friction. Budget constraints hampered the original TV series ending, and the team used this feature to unleash a more “accurate,” uncompromised version of that psychological imagery. Anno’s personal struggles with depression are well-documented, and through Shirai’s “lens,” you see them bleeding onto the screen.Shinji’s torment isn’t just a plot point; it’s a raw, unfiltered expression of a psyche in crisis. This isn’t just filmmaking; it’s catharsis. It’s the kind of expression that bypasses logic and hits you on a purely emotional, almost cellular level.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The driving force here was simple: go full force. The original series already pushed boundaries with its symbolism, but the movie cranks that dial to eleven. Shirai and the art team weren’t just trying to represent something else they were creating an “otherworldly appeal” that prioritized feeling over literal meaning. Think less “this represents X” and more “this feels like X.”

This taps into a Japanese filmmaking tradition that often prioritizes identity and human flaws over rigid plot mechanics. In Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion, the giant robots and the world-saving plot are almost an excuse a backdrop to show the tormenting path of these characters. The visuals don’t just show us what is happening; they force us to experience how it feels to be Shinji, struggling for an identity in a world that’s literally dissolving. Whether it’s a giant, ghostly Rei or a trippy Angel sequence, the creativity is designed to keep you trapped in that internal struggle.

Camera Movements

Even though it’s hand-drawn, the “camera” movements Shirai oversaw move with a precision that feels eerily physical. They mimic the characters’ heartbeats.

Look at Asuka’s iconic battle against the Mass Production Units. The camera isn’t a passive observer; it’s in the dirt. We get these dynamic, handheld-style movements that track her Eva as it tears through the sky. Every impact comes with a visceral frame shake. It’s manic. It’s desperate. It perfectly mirrors her 180-degree shift in mindset her newfound, violent determination to survive.

Then, the film hits the brakes. During Shinji’s internal collapses, the camera becomes agonizingly still. It hangs back in wide shots that make him look microscopic, or it pushes into a tight close-up that feels claustrophobic. When Instrumentality begins, the movement turns fluid and dreamlike. Slow pans. Ethereal drifts. The contrast is what gets you the violent immediacy of the fight versus the hollow stillness of the mind.

Compositional Choices

Composition in this film is a character in itself. It manipulates you.

The ending on the beach is the perfect example. After the “hope” of Instrumentality, we’re left with a stark, devastating frame. We see Shinji and Asuka from high above, isolated against a dark sky and a sea the color of an open wound. It’s lonely. Then, the camera moves closer, but they are blocked on opposite sides of the screen. Even though they’re the only two people left, the composition screams that the barriers are back. Connection isn’t easy.

I love how they use negative space, too. Shinji’s internal world is often just a void a “world of nothingness.” When he finally draws a single line to create reality, that one stroke against the empty frame is more powerful than a thousand explosions. It’s visual shorthand for the existential struggle to just exist.

Lighting Style

This is where the Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion moves away from realism and into pure emotional resonance. Shirai’s mastery of contrast and value is on full display here.

The film uses a style similar to chiaroscuro deep, bottomless shadows and stark highlights. This isn’t just for drama; it’s about the binary struggle of the soul. Hope versus despair. The Instrumentality sequence is bathed in “heavenly” light glowing crosses and stars against the dark. It feels optimistic, almost blissful.

But then, the floor drops out. We transition to the post-Instrumentality wasteland. The “heavenly” light is gone. The sky is dark, the land is ravaged, and the water is blood. This shift in “grading” (if you will) tells you everything. The dream is over. The red sea isn’t just a color, it’s a visual trauma that refuses to let you feel safe.

Lensing and Blocking

In animation, “lensing” is all about the perceived focal length. Shirai used wide angles during the NERV assault to create a sense of impending doom and scale. It feels grand, but the distortion at the edges of the frame makes you feel slightly sick. When Shinji is in his head, the film switches to a tighter, compressed feel. It’s claustrophobic.

The blocking is just as calculated. Look at Gendo and Shinji. Gendo is almost always looming, framed to emphasize his authority and that massive emotional distance. During Asuka’s fight, she dominates the center of the frame she’s the hero of her own story for a moment. But as she gets overwhelmed, her Eva starts getting swallowed by the edges of the frame. She looks like an underdog again. Every position in the frame is a statement on power.

Color Grading Approach

This is where my colorist brain really starts spinning. The grading here is aggressive and deeply deliberate.

The overall palette is often desaturated and gritty, mirroring the grim reality of NERV. You’ve got crushed blacks that swallow up the shadows, creating this pervasive sense of dread. But then you have these intentional bursts of hue separation. That “blood-red” water? It’s a specific, unsettling shade. It’s not “pretty” red; it’s “mass death” red.

When Shinji is spiraling, the palette shifts into psychedelic purples and oranges. These aren’t random; they’re tonal sculpting. The blinding whites of the “heavenly” sequences contrast so sharply with the oppressive grays of reality that it makes the “real” world feel even heavier. And those controversial live-action scenes? Their raw, uncorrected photographic color breaks the illusion. It’s a brave move forcing a confrontation with reality by deliberately ruining the visual “look” of the movie.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Being a 1997 release, this is a product of traditional cel animation, but it’s incredibly audacious.

The most potent tool here is actually the edit. Anno and Shirai use these long, uncomfortable shots that force you to sit in the character’s pain. You want to look away, but the edit won’t let you. Then, he’ll pivot into these rapid-fire, abstract montages that plunge you into a fractured mind. It’s a rhythmic manipulation of time.

Then there’s the sound or the lack of it. That final beach scene? No score. No “heavenly” music. Just the sound of red waves crashing. That silence speaks louder than any orchestra. It maximizes the impact of the visuals, forcing you to engage with the desolation. They used every tool available traditional cells, early digital effects, and even meta-photographs to serve one uncompromising vision.

- Also read: BLACKFISH (2013) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: THE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE (1962) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →