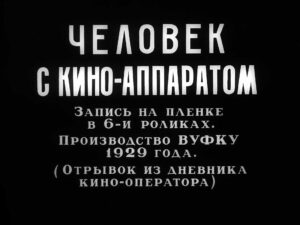

Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929). This isn’t just some dusty historical artifact you study in film school and forget. It’s a living, breathing masterclass in visual language that still feels more audacious than most of what hits theaters today. When I first watched it, I wasn’t just observing; I was practically vibrating with the kinetic energy Vertov managed to bottle. It’s the kind of film that makes you question why we ever got obsessed with “traditional” narrative in the first place.

About the Cinematographer

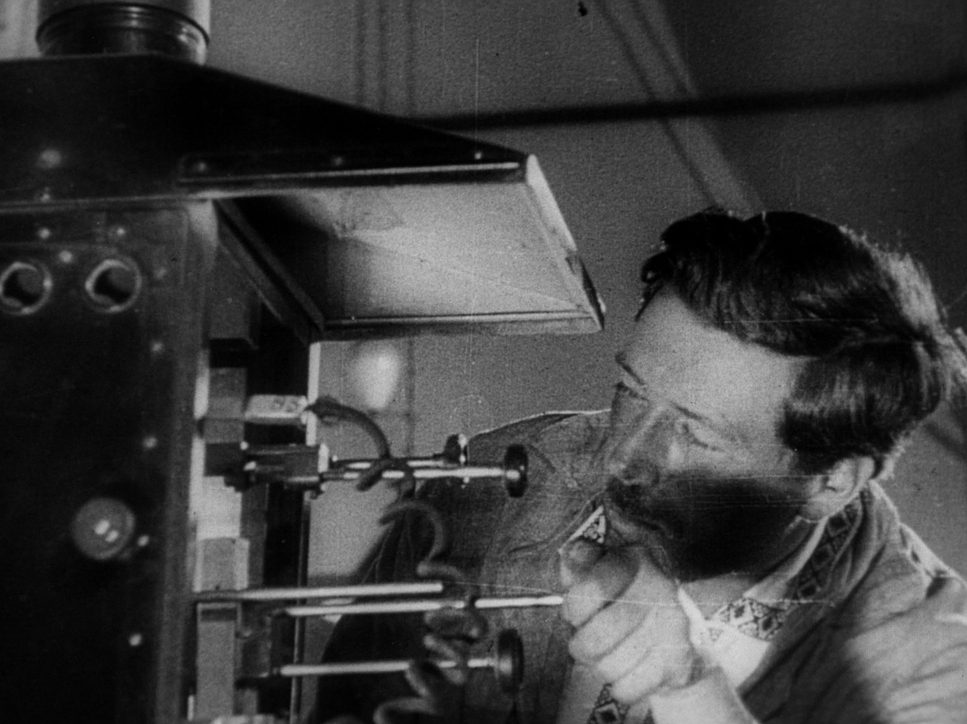

To understand why this film looks the way it does, you have to look at the visionaries behind the lens: Mikhail Kaufmanand Gleb Troyanski. While Vertov was the theoretical engine, Kaufman (Vertov’s brother) and Troyanski were the ones physically wrestling with the machinery to bring the “Kino-Eye” to life. Vertov’s chosen pseudonym, “spinning top,” perfectly captured their collective obsession with relentless motion.

They weren’t just cameramen; they were rebels. Vertov dismissed the narrative films of his time even the Soviet greats like Eisenstein as “fictions” that manipulated the masses. He famously called them “the same old crap tinted red.” Together with Kaufman and Troyanski, he pushed for Ney-Grovaya Filma, or “the unplayed film.” No actors, no sets, no scripts. Just life caught “unaware.” They didn’t want to be cinematographers in the traditional sense; they wanted to be a machine. “I am a mechanical eye,” Vertov wrote. He genuinely believed the camera was a superior form of perception that could see the “absolute truth” better than the biased, fallible human eye.

Technical Aspects & Tools

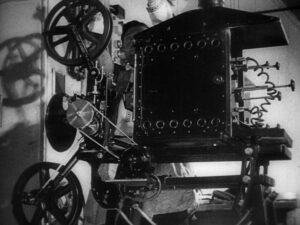

When I look at my DaVinci Resolve setup, I feel a bit spoiled. Kaufman and Troyanski were out there in the 1920s lugging around hand-cranked beasts like the Debrie Parvo L, the Debrie Sept, and the Zeiss Ikon Kinamo. No batteries,no monitors, just raw physical effort and a prayer that the hand-cranking was consistent.

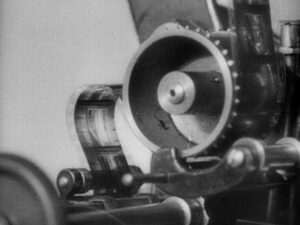

The film was shot on 35mm, using a mix of orthochromatic and early panchromatic stocks. If you’ve ever worked with old stock, you know the struggle: limited sensitivity meant the duo was constantly dancing with the sun to get a usable exposure. Every “trick” in the book double exposures, slow motion, split screens was done either in-camera by the cinematographers or through the manual, finger-shredding labor of the editor, Elizaveta Svilova. She didn’t have a “cut” command; she had a pair of scissors and a Moviola. It’s a literal catalog of every cinematic technique we still use today,birthed from sheer mechanical ingenuity.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Vertov, Kaufman, and Troyanski wanted to “emancipate the camera.” While other “city symphony” films of the era were essentially love letters to urban life, this team wanted to document the act of documenting.

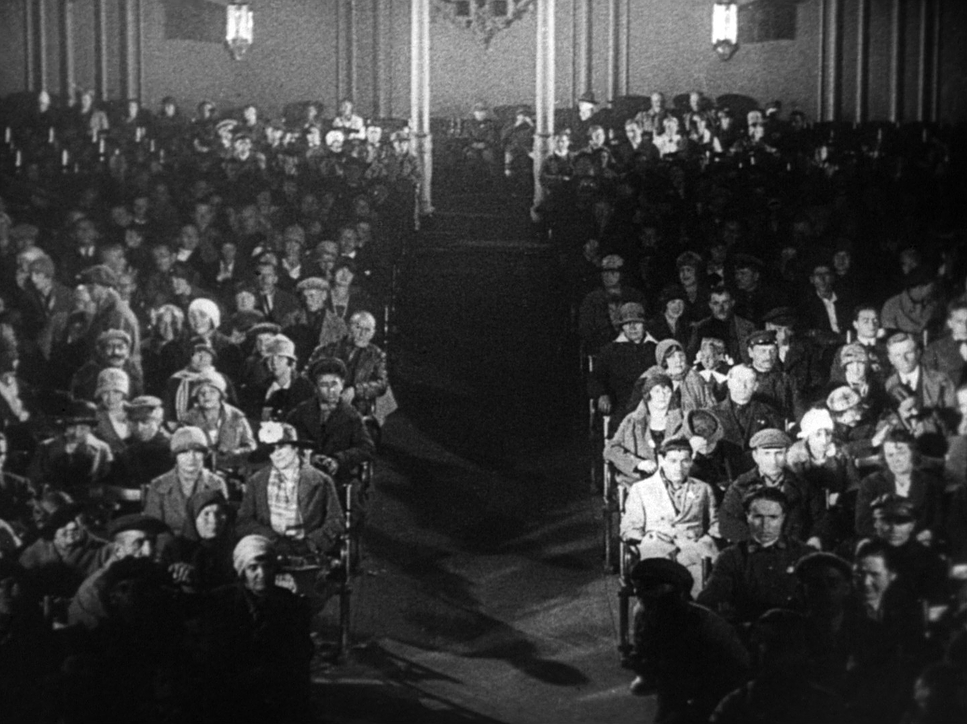

They wasn’t just showing you Odessa or Kharkiv; they were showing you the camera looking at them. The film starts in a movie theater a clever, self-referential move that mirrors our own experience. They wanted to reveal a world “more true than anything our eyes could conceive.” As a filmmaker, I find this ambition both noble and a bit paradoxical. They stitched together footage from different cities (Odessa, Kyiv, Kharkiv) to create the illusion of “one” Soviet city. So, was it “truth,” or was it a meticulously crafted idea of truth? That’s the question that keeps me up at night.

Camera Movements

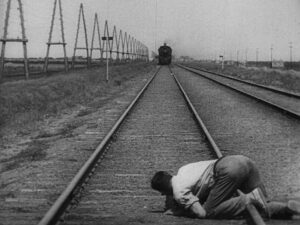

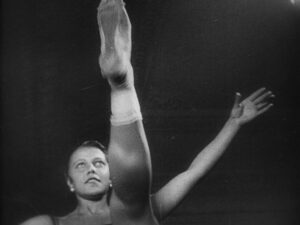

The camera movements here are revolutionary and I don’t use that word lightly. Kaufman and Troyanski broke the camera free from its tripod-bound prison. We see it mounted on the back of moving cars, positioned between train tracks as a locomotive thunders over it, and even ascending in airplanes.

It’s visual percussion. The handheld shots pull you into the crowd, while the Dutch angles add this dizzying, modern energy to the landscape. Vertov makes a point of showing us Mikhail Kaufman actually performing these stunts. By revealing the “how,” he strips away the cinematic illusion and makes the audience marvel at the mechanics. For a colorist, this constant movement is a challenge you have to think about how to maintain visual focus when the frame is constantly shifting. It’s like trying to grade a lightning bolt.

Lensing and Blocking

In this film, “blocking” isn’t about actors hitting marks; it’s about the blocking of the camera itself. Under the direction of Vertov and the eyes of Kaufman and Troyanski, the camera “crawls,” “climbs,” and “dives.” It’s an active participant in the scene.

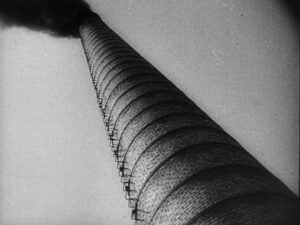

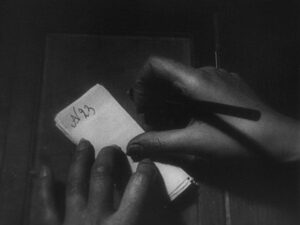

They utilized Medium and Wide lenses to capture the industrial sprawl of the Soviet Union, but they also used the lens to create depth in a flat, black-and-white medium. By placing objects a tram, a worker’s hands deep in the foreground against a distant background, they created a 3D sense of space that was light-years ahead of its time. It’s a reminder that you don’t need a fancy gimbal to create immersive movement; you just need a clear sense of where the “eye” should be.

Lighting Style

For the most part, this is a masterclass in available light. Being a documentary, the cinematography team had to work with what the sun gave them. They used the angle of the light to sculpt factory machinery and morning light to reveal the textures of a waking city.

However, we also see the use of artificial light in the interior theater scenes a specific choice noted in the film’s records. The contrast between the harsh, directional side-light in the factory and the controlled, interior glow of the cinema highlights the film’s dual nature. As a colorist, I look at those 1920s highlights the metallic sheen of a train or the glint of sunlight on water and I’m floored by how much detail they managed to hold onto with such primitive technology.Compositional Choices

Compositional Choices

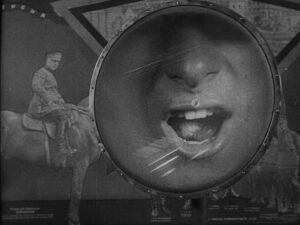

The composition here is all about “constructive realism.” The team used “frames within frames” think windows and doorways to isolate subjects. But the real magic happened in the edit suite.

The film uses intellectual montage to create meaning through juxtaposition. A funeral is cut against a birth; a marriage against a divorce. These aren’t just pretty shots; they are deliberate choices that force the viewer to make a cognitive leap. When I’m grading, I’m always thinking about the relationship between shots. How does the “weight” of one frame affect the next? Vertov and Svilova understood this perfectly.

Color Grading Approach

Even though we’re talking about a monochrome film, my “colorist brain” can’t help but imagine how to grade this for a modern restoration. It’s not about adding color; it’s about tonal sculpting.

If this were on my desk today, I’d focus on “punchy” contrast for the industrial scenes to emphasize the grit, while using a softer curve for the more human, introspective moments. Hue separation in B&W translates to gray values. I’d want to make sure the “red” of a brick building and the “blue” of the sky don’t just turn into the same muddy gray. I’d be obsessing over the highlight roll-off, making sure the glint of the sun on the camera lens feels organic and “filmic” rather than clipped and digital. It’s about honoring the “absolute truth” of the original negative while making it sing for a modern audience.

Man with a Movie Camera (1929) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA (1929). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: A MAN ESCAPED (1956) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: DERSU UZALA (1975) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →