Magnolia (1999) is one of those movies that makes me jealous. I spend most of my waking hours in a dark room at Color Culture, tweaking curves, staring at scopes, and building DCTLs to help people get “the film look.” Then I put on this 1999 masterpiece and realize: this is the bar.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s epic doesn’t just “have good cinematography.” It has a visual pulse. It’s messy, it’s three hours long, and it breaks a lot of conventional rules. But that’s exactly why it works. It resonates not because it’s perfect, but because it feels like a raw, unpolished nerve. Watching it today, twenty years later, it’s a humbling reminder of what analog workflows could achieve before we all started relying on power windows and qualifiers to fix things in post.

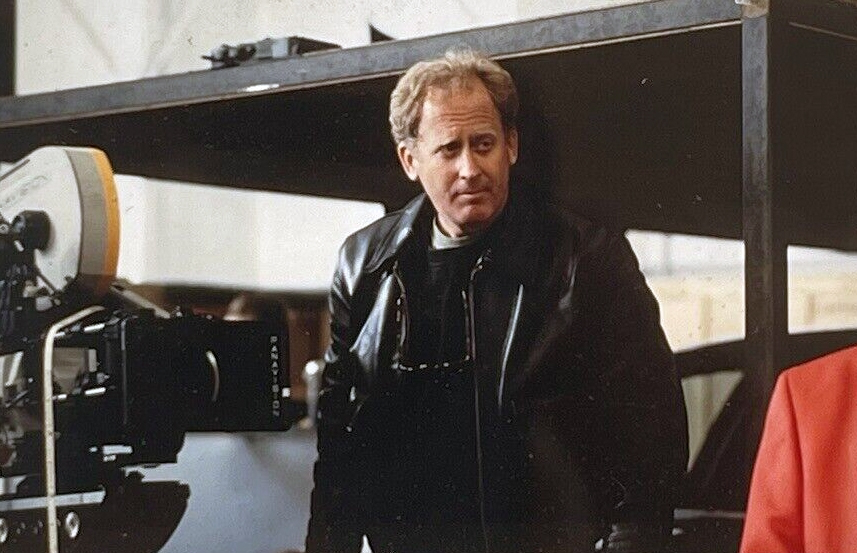

About the Cinematographer

Robert Elswit shot this. If you know PTA’s early run Hard Eight, Boogie Nights you know that Elswit isn’t just a technician; he’s the grounding force to Anderson’s manic energy. This wasn’t a “point and shoot” gig. They were dealing with a massive ensemble, night shoots, and a script that demanded the camera feel like an omniscient narrator.

Elswit brought a specific visual signature that defined this era of PTA’s work. He understands how to move a camera through a space without it feeling mechanical. He took Anderson’s desire for a film that felt like “the conclusion of a 20-year daytime drama” and shot it with the weight of a biblical epic. It’s a collaboration that speaks to deep trust knowing exactly when to light a scene beautifully and when to let it look a little ugly and uncomfortable for the sake of the story.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

PTA was working through some heavy stuff here specifically the death of his father and that emotional baggage is baked into the image. The film is obsessed with regret, fathers, and the San Fernando Valley. But not the glossy Hollywood version; this is the Valley of strip malls, dive bars, and lonely apartments.

Visually, the challenge was cohesion. How do you make nine different storylines feel like one movie? Elswit and Anderson used the camera to forge those links. The setting isn’t just a backdrop; it’s a crucible. The harsh Southern California light plays a huge role here. The camera acts as the “hand of God,” moving between characters who never meet, suggesting that they are all part of the same predetermined mess. It’s a bold choice the camera is practically a character itself, observing these impossible coincidences with a steady, unblinking gaze.

Camera Movements

If I had to describe Magnolia’s camera work in one word, it’s relentless. The film moves. It breathes. It has this kinetic energy that refuses to let the audience settle. But it’s not shaky-cam chaos; it’s precise. We’re talking about heavy, studio-mode camera movement controlled dollies, massive crane shots, and Steadicam moves that last for minutes.

Look at the “Seduce and Destroy” seminar with Frank T.J. Mackie. The camera whirls around him, feeding off his manic charisma. Then you have the long takes. In modern filmmaking, we often cut to save pace. Here, the camera holds. It pushes in slowly, forcing you to sit in the discomfort of a silence. Or it whip-pans violently to a new subject, amplifying the confusion. It creates this breathless tension where you feel like you’re being swept along by a current you can’t control. It’s technical flexing, sure, but it serves the narrative: these characters are losing control, and the camera movement reflects that spiral.

Compositional Choices

Elswit and Anderson shot this Anamorphic (2.39:1), and they used every inch of that wide frame. The composition constantly plays with isolation. You’ll often see a character “short-sided” in the frame pushed to the edge with a lot of empty space behind them visually reinforcing that they have nowhere to go.

There’s a distinct difference between the public and private worlds. When Frank Mackie is on stage, he dominates the frame he’s larger than life. When Jimmy Gator is on his game show set, the composition is symmetrical, rigid, artificial. But cut to their private lives, and the framing becomes cluttered, claustrophobic, using foreground elements to block our view slightly. It feels like we’re spying. They also use deep focus brilliantly to manage the ensemble; you often have multiple layers of action happening at once, forcing your eye to scan the frame to catch the dynamics of the group. It organizes the narrative chaos into a visual logic.

Lighting Style

The lighting in Magnolia is what I’d call “heightened reality.” It’s driven by practicals lamps, TV screens, overhead fluorescents but it’s polished. Elswit isn’t afraid of hard light. There’s a lot of high-contrast side lighting, especially in the interiors, which carves out the actors’ faces and emphasizes the texture of their skin (and their stress).

As a colorist, I love looking at the mixed color temperatures here. You have the cool, blue moonlight or HMI ambience cutting through windows, mixing with the warm, tungsten glow of practical lamps inside. It creates natural color separation without feeling “graded.” The game show sequences are particularly great lit with harsh, flat television lighting that feels sterile compared to the moody, shadow-heavy look of the apartment scenes. And when the rain starts? The light shifts to this diffuse, gray softness that changes the entire mood of the film. It feels organic, motivated, and incredibly effective.

Lensing and Blocking

They leaned heavily on Panavision glass here likely C-Series or E-Series anamorphics. They often used wider focal lengths, even for close-ups. This is crucial because a wide lens forces the audience to see the environment around the actor. You can’t separate the character from their lonely apartment or the hospital room.

The blocking is a masterclass in staging. Because they committed to those long takes, the actors had to hit marks perfectly. It’s a dance. Watch how characters enter and exit the frame; they aren’t just walking in, they are revealing power dynamics. Frank commands space; Donnie Smith looks small and swallowed by it. The blocking often physically separates characters even when they are in the same room, visually articulating their emotional distance. It’s old-school filmmaking craft solving problems on set with blocking and lenses rather than fixing it in the edit.

Color Grading Approach

From a color perspective, Magnolia is a love letter to Kodak Vision 500T (5279). That stock was the workhorse of the 90s grainy, fast, and with a latitude that just ate up shadows. The look of this film is decidedly “Cool, Saturated, Blue,” especially in the night exteriors, but it retains that thick, warm skin tone that film manages so effortlessly.

The “grade” here was done photochemically by color timer Phil Hetos at the lab, not on a DaVinci panel. You can see the difference in the highlight roll-off. When practical lights blow out in the background, they don’t clip to a harsh digital white; they bloom and roll off gently. The shadows are lifted just enough to see the detail the “toe” of the film curve isn’t crushed to black, giving scenes a slightly milky, heavy atmosphere that fits the melancholy tone.

There’s also a subtle use of color contrast. The interiors lean warm (tungsten), while the exteriors are pushed toward cyan and blue. This separation helps orient the viewer instantly. It’s not the teal-and-orange look we see everywhere today; it feels like a natural reaction of the film stock to different light sources, enhanced in the lab to feel cohesive.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Magnolia (1999)

Technical Specifications| Genre | Drama, Magical Realism |

|---|---|

| Director | Paul Thomas Anderson |

| Cinematographer | Robert Elswit |

| Production Designer | William Arnold, Mark Bridges |

| Costume Designer | Mark Bridges |

| Editor | Dylan Tichenor |

| Colorist | Phil Hetos |

| Time Period | 1990s |

| Color Palette | Cool, Saturated, Blue |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.39 – Anamorphic |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | High contrast, Side light |

| Lighting Type | Moonlight, HMI |

| Story Location | Los Angeles > San Fernando Valley |

| Filming Location | California > Los Angeles |

| Camera | Panavision Millennium, XL/XL2, Platinum, Gold G2, Panaflex |

| Lens | Panavision Primo Primes, C-Series, E-Series |

| Film Stock | 5279/7279 Vision 500T, 5248/7248 EXR 100T, Plus X 5231, 5222/7222 Kodak Double X |

In 1999, this was a strictly analog production. They shot on 35mm using Panavision Millennium and Platinum cameras. The primary stocks were likely Kodak Vision 500T 5279 for the interiors and night scenes, and EXR 100T 5248 for the sharper, cleaner day shots.

Why does this matter? Because 500T 5279 had a distinct grain structure. It added a texture to the image that made it feel alive. It wasn’t clean. It wasn’t noiseless. The film grain acts like a subtle veil that ties all these disparate storylines together. To get those shots, they needed heavy iron large studio dollies, cranes, and experienced operators who could pull focus on anamorphic lenses wide open.

This was a film made by human hands, physically cutting negative and timing lights in a lab. The texture, the grain, the slight imperfections in the anamorphic glass that’s the “heart” of the image. It proves that technical perfection isn’t the goal; emotional resonance is.

- Also read: MARRIAGE STORY (2019) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: BOYHOOD (2014) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →