I spend my days deep in the visual language of cinema, but occasionally, a film comes along that reminds you just how foundational the craft is—how long it’s been evolving and how deeply it can cut. Fritz Lang’s 1931 masterpiece is one of those films. It’s often lauded for its pioneering use of sound, and rightly so, but for me, its visual storytelling is just as groundbreaking. It set a high bar for every psychological thriller and film noir that followed. It’s a film that demands an answer to a difficult question, and it uses every tool in the cinematic arsenal—not just sound, but light, shadow, and movement—to build its argument. It’s a masterclass in letting the camera itself become a participant in the unfolding drama, rather than just a passive observer.

About the Cinematographer

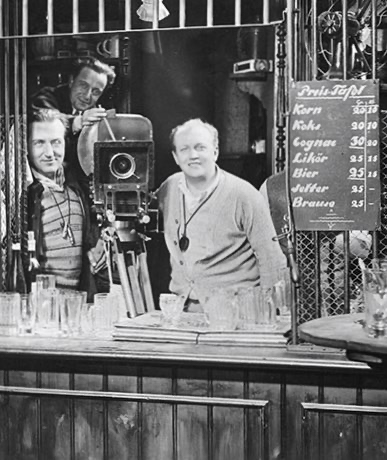

When we discuss the look of M, we have to give credit to Fritz Arno Wagner. While Fritz Lang clearly had a powerful vision for the film’s aesthetic—structuring the entire film as a visual argument built through blocking and montage—it was Wagner who translated that vision into tangible light and shadow. Wagner was a heavy hitter in Weimar Germany, known for his work on Expressionist classics like Nosferatu. He understood how to harness the raw power of visual tension, how to make a frame breathe with anxiety or suffocate with dread. It’s a testament to the partnership that Lang could articulate such a complex visual philosophy and Wagner could execute it so flawlessly, especially within the technical nightmares of early sound cinema. For me, that collaboration between director and DP is always the sweet spot; it’s where the abstract concept meets the concrete reality of light hitting emulsion.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The visual language here is deeply rooted in German Expressionism, a movement that embraced exaggerated sets and distorted perspectives to convey subjective emotional states. You see echoes of this throughout M, particularly in the stark contrast and ominous shadows that permeate the urban landscape. But it’s more than just an aesthetic flex; it serves a specific purpose. The film’s primary goal is to present a carefully constructed moral and philosophical inquiry. How do you make an audience feel that inquiry, internalize it, and grapple with its implications? You do it through visual design that heightens paranoia, suspicion, and the feeling of a city under siege.

Lang and Wagner essentially crafted the visual blueprint for what would later become film noir. The pervasive darkness, the deep shadows, the sense of a world where morality is murky and danger lurks in every alley—it’s all here. The use of light and shadow informed the entire noir look that followed. They weren’t just making a film; they were defining a visual lexicon for a genre that understands that what you don’t see is often far more terrifying than what you do. The visual style isn’t decoration; it is the argument itself, forcing us to confront unseen dangers and the blurred lines between justice and vengeance.

Camera Movements

This is where M really shows off its muscles as an early sound film. The common wisdom of the early talkies era was that cameras had to be static, often encased in soundproof booths (“blimps”), making dynamic movement a rare and cumbersome feat. Lang and Wagner clearly rejected that limitation. While dynamic camera work wasn’t entirely unheard of in the sound era, it was usually reserved for giant set pieces. Here, it’s used for psychological impact.

We see the camera following characters, zooming in, tracking side to side, or booming up and down. This isn’t just for spectacle; it creates a living, breathing, and creepy atmosphere. Think about the tracking shot where Becker follows Elsie, or later, when the camera itself follows Becker as he’s being hunted. These movements act as a character. The camera isn’t just observing; it’s stalking. It takes on the role of an unseen presence, hidden in the shadows, watching the characters. This creates a palpable sense of unease. It makes the audience feel like they are always a step behind—or perhaps a step ahead, knowing what’s coming but powerless to stop it. This mobile cinematography laid the groundwork for the visual language of thrillers for decades to come.

Compositional Choices

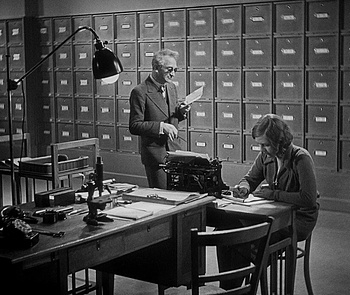

The compositions in M are lessons in conveying psychological states through geometry. Lang and Wagner frequently employ deep space, allowing multiple planes of action to coexist, which enhances the sense of a complex, interconnected world. This technique is particularly effective in showing the scale of the police investigation or the sprawling criminal underworld.

They use framing to isolate characters to emphasize vulnerability or, conversely, group them to highlight collective anxiety. There is a specific shot with one person surrounded by other people in a tight circle that stands out. This almost ritualistic, inescapable framing speaks volumes about the individual caught within the group’s gaze, whether it’s Elsie before her disappearance or Becker at his kangaroo court. It’s a perfect visual representation of the film’s core moral dilemma: the individual against the collective.

And then there’s the famous moment when Becker, realizing he’s being followed, looks directly into the lens. That’s not just a break of the fourth wall; it’s an intensely confrontational compositional choice. It shatters the illusion of the audience as detached observers and implicates us directly in the hunt. It reveals Becker’s identity to us, but also turns the tables, making us feel seen by the villain. That kind of compositional courage was revolutionary.

Lighting Style

The lighting in M is, without a doubt, its defining characteristic. It’s a chiaroscuro wonderland, pulling from Expressionist traditions but applying them with a new psychological depth. Lang and Wagner use hard, directional light sources to sculpt faces and environments, creating deep, impenetrable shadows that conceal as much as they reveal.

We see strong contrasts that carve out figures from the darkness. Motivated lighting often comes from practical sources like streetlights, windows, or single bulbs in cramped interiors, but it’s always stylized to heighten the dramatic effect. Sometimes, the lighting feels unmotivated, simply existing to create a mood—a splash of light across a wall, a sudden fall into darkness—serving the film’s overarching tone of paranoia.

The famous shadow of the murderer across his own wanted poster is the prime example of this genius. It’s a simple visual, yet it’s chillingly effective, making the unseen tangible and adding a layer of sadism to the crime. Using shadows as narrative devices—as extensions of character or impending doom—is pure noir poetry. It builds tension and makes the world feel bigger and more dangerous, even when you don’t explicitly see the threat. The play of light and shadow isn’t just pretty; it’s an active participant in the story.

Lensing and Blocking

Given the era, the lensing choices in M would have been limited compared to today’s vast array of glass. However, the brilliance lies in how they maximized the tools they had. They likely relied on standard-range primes, probably in the normal to slightly wide-angle range (think 35mm or 50mm equivalents), to capture the depth of the cityscapes and the claustrophobia of interiors. The subtle distortion of wider lenses adds to that Expressionistic feel, subtly warping perspectives to reflect the city’s psychological torment.

Blocking—the precise arrangement of actors within the frame—is where much of the film’s spatial tension lives. Characters are often blocked in ways that emphasize their isolation or their collective power. Consider the scenes where the police or the criminals are organizing their manhunt; the careful staging of these groups, often in tight, almost geometric formations, speaks to their machine-like pursuit. Conversely, Becker himself is often shown in isolation, hemmed in by the architecture, visually representing his internal struggle.

When characters move, the blocking dictates the viewer’s gaze. The way Becker navigates the city, constantly glancing over his shoulder, is visually reinforced by how he’s placed in relation to other pedestrians and buildings—sometimes swallowed by the crowd, sometimes exposed in open space. This careful choreography contributes immensely to the film’s narrative momentum.

Color Grading Approach

Now, this is where I geek out a bit. We are talking about a black-and-white film, so “color grading” in the modern sense didn’t exist. However, the decisions made in the lab during development and printing were essentially the “monochromatic grading” of the era. These were crucial choices that dictated the film’s contrast curve, tonal range, and emotional impact.

Looking at M, there is a deliberate effort to create a very specific grayscale palette. The deep blacks aren’t accidental; they are the result of careful exposure and print decisions to create incredibly strong contrast ratios. These dense shadows aren’t just “dark”—they are voids. They swallow light. In modern grading terms, we’d say the “toe” of the curve is crushed just enough to remove noise but keep the threat, making figures emerge sharply from the gloom.

The highlights are often piercing, almost blowing out in places. Combined with the deep shadows, this gives the film a stark, brutal realism. There’s a distinct print-film sensibility here—a richness and texture that comes from photochemical processes. We aren’t just looking at black and white; we’re seeing charcoal, midnight grays, and spectral whites. The way these tones are sculpted evokes specific feelings: oppressive doom in the shadows, stark exposure in the highlights. Modern digital grading often obsesses over “hue separation,” but in B&W, it’s about separating textures and details across the tonal spectrum. M achieves incredible clarity in its tonal sculpting. Even in the deepest shadow, you sense a hidden detail. That is sophisticated grading, even if they didn’t have a control panel to do it.

Technical Aspects & Tools

M – Technical Specs

| Genre | Action, Crime, Drama, Gangster, German Expressionism, Murder Mystery, Mystery, Serial Killer, Thriller, Courtroom Drama, Film Noir, Police |

| Director | Fritz Lang |

| Cinematographer | Fritz Arno Wagner |

| Production Designer | Emil Hasler, Karl Vollbrecht |

| Editor | Paul Falkenberg |

| Time Period | 1930s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.20 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, High contrast |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light |

| Story Location | … Germany > Berlin |

| Filming Location | … Europe > Germany |

Considering M was made in 1931, the technical achievement is staggering. Early sound cameras were notoriously bulky and loud, often requiring a soundproof booth which severely restricted movement. Yet, M boasts incredibly dynamic camerawork. This suggests Lang and Wagner employed innovative workarounds—carefully constructed dollies, hidden camera setups, or perhaps early experiments with post-synchronization (dubbing) to allow for freedom on set.

The film stock of the era was also relatively slow (low ISO in modern terms), demanding massive amounts of light to get an exposure. This necessity likely contributed to the stark, high-contrast look that became the film’s signature—you needed hard light just to see anything. The lenses, while less advanced than today, were used with a masterful understanding of perspective. They didn’t have the luxury of variable focal lengths or complex zooms, so every push-in or pull-out was a physical dolly move, a meticulously choreographed dance between camera and actors.

It makes me wonder about the logistics—how many takes did it take to get a smooth tracking shot with a blimped camera? Or to hide the camera behind obstacles while ensuring clear audio? These weren’t easy feats. It’s a testament to the ingenuity of filmmakers like Lang and Wagner that they pushed the boundaries of the medium even when the technology tried to fight them.

- Also Read: THE APARTMENT (1960) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also Read: INCENDIES (2010) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →