Let’s get one thing straight: Le Samouraï is a mood. It’s a masterclass in how visual language can sculpt a character when the script refuses to do the heavy lifting. Jean-Pierre Melville, alongside the legendary Henri Decaë, didn’t just make a gangster flick they created a transcendent piece of “visual quiet.” Today, I want to break down the technical intentionality that makes this film feel as sharp and cold as a razor blade, even decades later.

About the Cinematographer

Henri Decaë was the secret weapon of the French New Wave. The man worked with everyone Malle, Chabrol, Truffaut but his partnership with Melville was something special. Decaë had this rare ability to balance a naturalistic “documentary” feel with high-style theatricality.

For Le Samouraï, Decaë was the only choice. He understood that Melville wasn’t looking for flashy camerawork; he wanted austerity. Decaë’s work here is meticulous and understated. He knew exactly how to let a shadow define a character’s internal landscape or make a standard Parisian apartment feel like a sterile cage. It’s a lesson in restraint that many modern DPs could learn from.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Melville was vocal about his philosophy: “A film is first and foremost a dream.” He wasn’t interested in a 1:1 recreation of reality. That’s why the film feels so ethereal. He took the DNA of Golden Age Hollywood Noir the hard shadows and existential dread and filtered it through the ritualistic precision of Japanese Samurai culture.

The most striking thing is the “stripping away.” Melville gutted the dialogue and backstories to force us to focus on Jeff Costello’s immediate reality. This put a massive burden on the cinematography. Every frame had to communicate Jeff’s isolation. Decaë embraced this, using a deliberately drab palette to articulate a “world full of immorality and corruption.” He turned Paris into a cold, indifferent urban maze. No romance, no postcards just cold stone and steel.

Lighting Style

Now, let’s talk about the light. If you look at the technical metadata for certain scenes, you’ll see “soft light, low contrast, daylight.” But when you watch the film, you remember it as a high-contrast Noir. Why the discrepancy? Because Decaë was a master of context.

While the exteriors often utilize the flat, soft light of a gray Parisian day, the interiors are pure chiaroscuro. Shadows aren’t just dark spots; they are active participants. Decaë used shadows to isolate Jeff, hinting at his moral ambiguity. Faces are often half-lit, leaving “shadows of doubt” everywhere. One detail I love: Jeff almost never has a double shadow, reflecting his singular, resolved nature. Meanwhile, the police officers often cast multiple shadows, visually representing their uncertainty. That’s not just lighting; that’s visual storytelling at its most elite.

Color Grading Approach

This is where my colorist brain starts firing. People often say Melville “removed color,” but it’s more accurate to say he subjugated it. If I had this film on my DaVinci Resolve wheels today, my focus wouldn’t be on saturation it would be on tonal sculpting.

The goal here is a restricted, almost monochromatic palette. We’re talking about pushing the blues into a cold, cyanic gray think smog and aged concrete. I’d be fighting to keep the mid-tones muted while ensuring the blacks have enough density to feel heavy without “crushing” the crucial shadow detail Decaë worked so hard to capture. The highlight roll-off needs to be gentle and organic, emulating that classic print-film look. It’s about creating a “dirty” yellow or olive for the warm tones, never letting them become vibrant. It’s a world bereft of joy, and the grade has to prove it.

Compositional Choices

Decaë’s compositions are all about entrapment. Jeff is constantly framed within “frames” doorways, windows, and those long, oppressive corridors. Even in the opening shot, he’s tucked away in the corner of a room with massive ceilings. It makes him look small, almost insignificant against the weight of the world.

Then there’s the bird. The bird in the cage is the most obvious visual metaphor in cinema history, but it works because Decaë mirrors Jeff’s blocking with the bird’s confinement. The sparseness of the apartment—no clutter, no “life”—allows Jeff’s stoic movements to fill the compositional void. It’s geometry as destiny.

Camera Movements

Movement in Le Samouraï is a study in tension. While everyone remembers the subway chase, the film’s real power lies in its stillness. As filmmakers, we’re often told to “keep the camera moving,” but Melville and Decaë knew better. They used “visual quiet” to force the audience to lean in.

When the camera does move, it’s smooth, clinical, and purposeful. It doesn’t “dance”; it stalks. During the subway sequences, the camera follows Jeff with a detached precision that mirrors his own. As Roger Ebert famously noted, action is often the enemy of suspense because it releases tension. Melville builds that tension by holding the shot, letting the character’s methodical nature dictate the rhythm. It’s mesmerizing.

Lensing and Blocking

We can see the lens choices through the film’s perspective. Decaë likely leaned on standard 35mm and 50mm glass to keep the perspective natural. However, you can feel the use of wider lenses (28mm or 35mm) in those tight interiors to make the architecture feel like it’s pressing in on the actors.

The blocking is where Alain Delon shines. His performance is purely physical. He moves with a ritualistic grace, and the camera is always positioned to catch the micro-details of his trade checking a pulse, breaking into a car, adjusting his hat. It’s a slow, deliberate choreography. The camera doesn’t just record the action; it observes a ritual.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Shooting in 1967 meant no digital safety nets. They were likely using Arri 2C or Eclair cameras on 35mm stock. Shooting those low-light interiors on slow-speed film (likely 50-100 ASA) was a high-wire act. It required precise gaffing to hide tungsten lamps within the sets to sculpt the light without blowing out the highlights.

The lenses likely classic Cooke or Angénieux glass gave the film that “dreamlike” texture Melville wanted. Those lenses have a specific fall-off and flare that digital sensors still struggle to replicate. Every grain of silver on that film was earned through technical expertise and a singular vision.

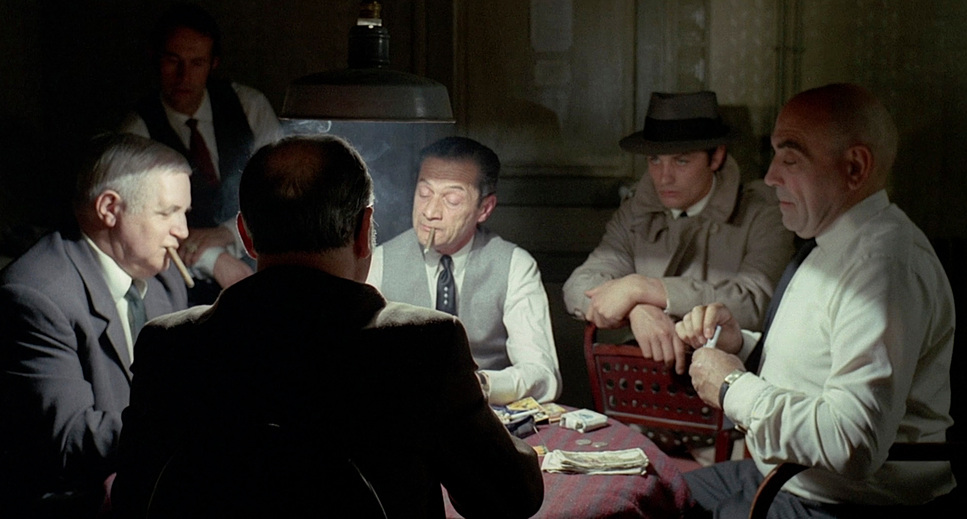

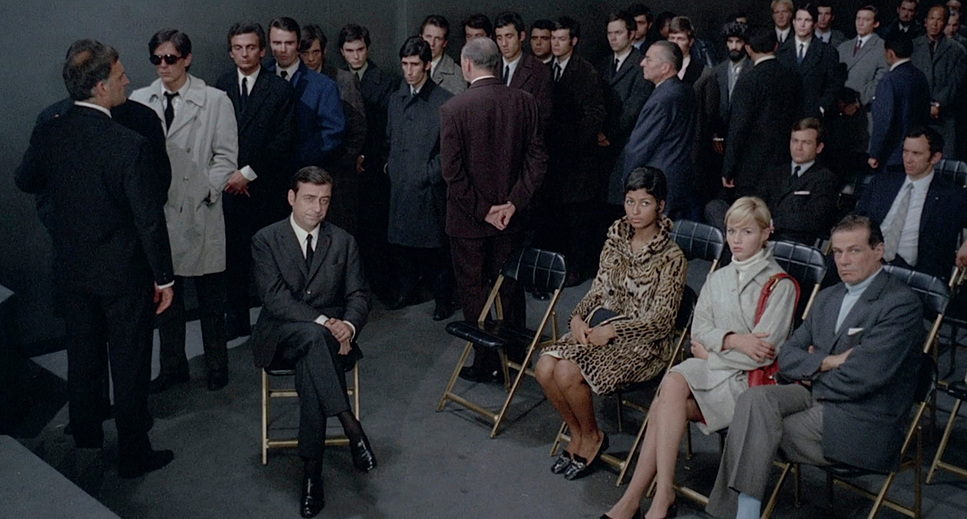

Le Samouraï (1967) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from Le Samouraï (1967). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: MOMMY (2014) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE? (1962) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →