As a professional colorist at Color Culture, I spend most of my waking hours in a dark room, staring at screens and obsessing over curves. When you look at images all day for a living, you stop seeing just the “movie” and start seeing the mechanics—the lighting ratios, the blocking, the grade. That’s why I wanted to revisit Jurassic Park (1993). It isn’t just a nostalgia trip; technically, it is a manual on how to ground the impossible. Spielberg and his team didn’t just rely on the novelty of CGI; they used old-school filmmaking mechanics to sell the illusion.

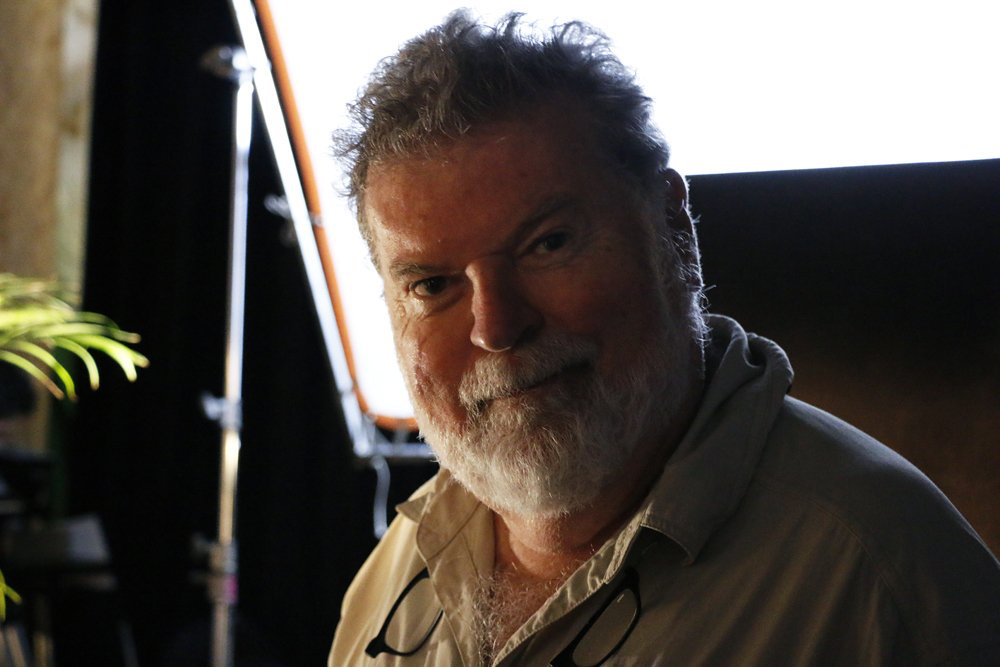

About the Cinematographer

The visual architect here was Dean Cundey. If you know his work with John Carpenter on Halloween or The Thing, you know he’s a master of doing a lot with a little. He knows how to light for atmosphere and how to make shadows feel dangerous. Spielberg hired him for a specific reason: to bring that grounded, gritty reality to a high-concept fantasy. Cundey isn’t a DP who shows off with flashy, unmotivated camera moves. His lighting is precise, and his framing is functional. He doesn’t just want the shot to look pretty; he wants it to feel physical. That restraint is exactly why the film holds up thirty years later.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The core problem Jurassic Park had to solve was the “6-ton animal” issue. How do you make a rubber puppet or a CGI wireframe feel like it has genuine mass? Spielberg’s strategy was to balance “real wonder” with “peak thrills.” The visual language had to pivot from a National Geographic documentary style in the first half to a slasher film in the second.

The cinematography carries the weight of that transition. Cundey and Spielberg had to answer a simple question: How would a human actually react to seeing this? The answer was usually to keep the camera at eye level, anchoring the visual experience to the characters. You don’t just see the T-Rex; you see it from the perspective of a terrified person stuck in a jeep. The pacing of these visuals is deliberate they earn the terror by giving you the wonder first.

Camera Movements

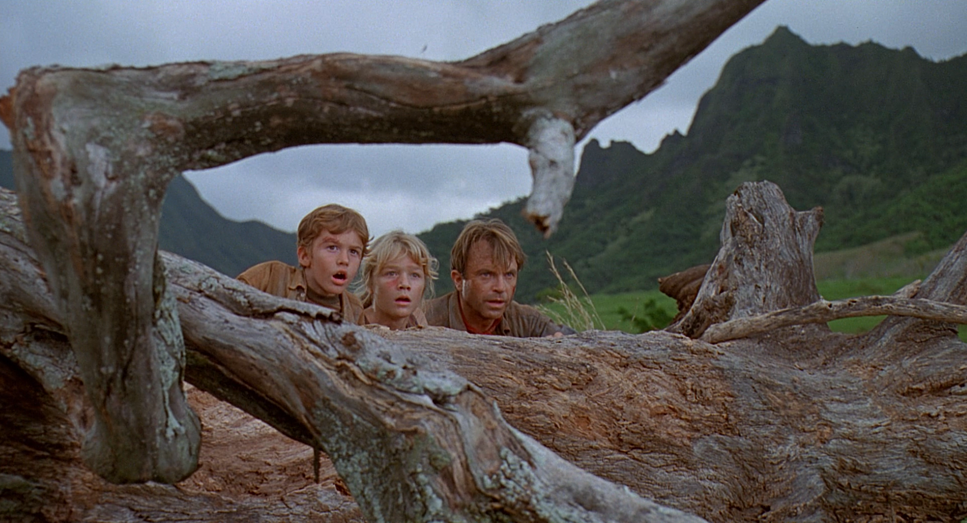

The camera work here is disciplined. Cundey uses movement to dictate scale. Look at the Brachiosaurus reveal: the camera starts low (using a Panavision Panaflex Platinum), grounded with the actors, and then tilts up, and up, and up. It forces the audience to physically crane their necks along with the characters. It communicates height better than a wide drone shot ever could.

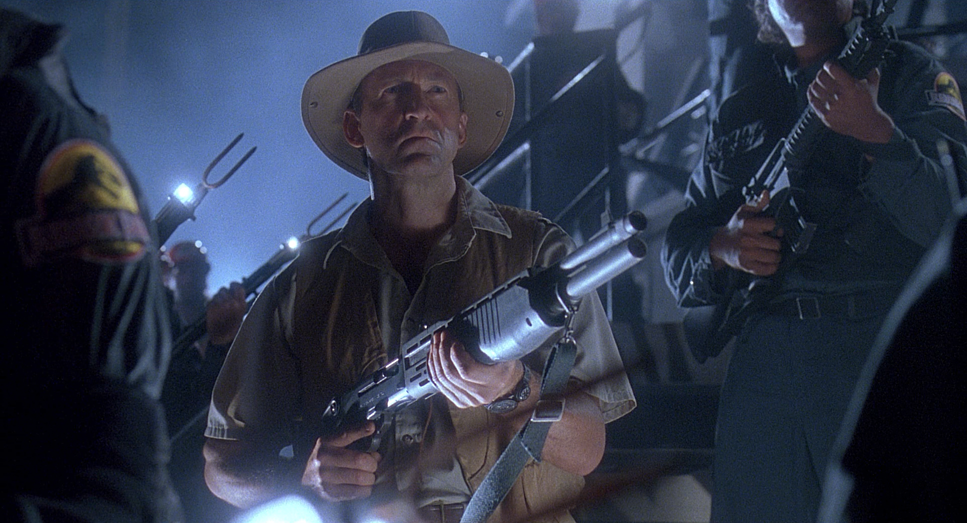

Contrast that with the T-Rex attack. The smooth pans are gone. We get frantic handheld work inside the Explorer. The camera shakes, reacting to the impact of the dinosaur. It creates a “dynamic dance” between the observer and the threat. The camera isn’t just recording the action; it’s reacting to it, often tracking backwards to emphasize the vulnerability of the humans running away.

Compositional Choices

This is where the tech specs really matter. Jurassic Park was shot in 1.85:1 aspect ratio (Spherical), not the wider 2.39:1 anamorphic format usually reserved for blockbusters. This was a critical tactical decision.

Dinosaurs are tall. Humans are short. The 1.85 ratio gave Spielberg more vertical headroom. He could frame a human at the bottom of the screen and a T-Rex head at the top in a single shot without cutting. If they had shot anamorphic, they would have been forced to cut to a wide shot to fit the dinosaur in, breaking the tension.

Cundey also loved “framing within a frame.” He constantly shoots through obstacles rain-slicked windshields, jungle foliage, computer room glass. It creates a voyeuristic, claustrophobic feeling. It traps the characters (and the audience) in the environment.

Lighting Style

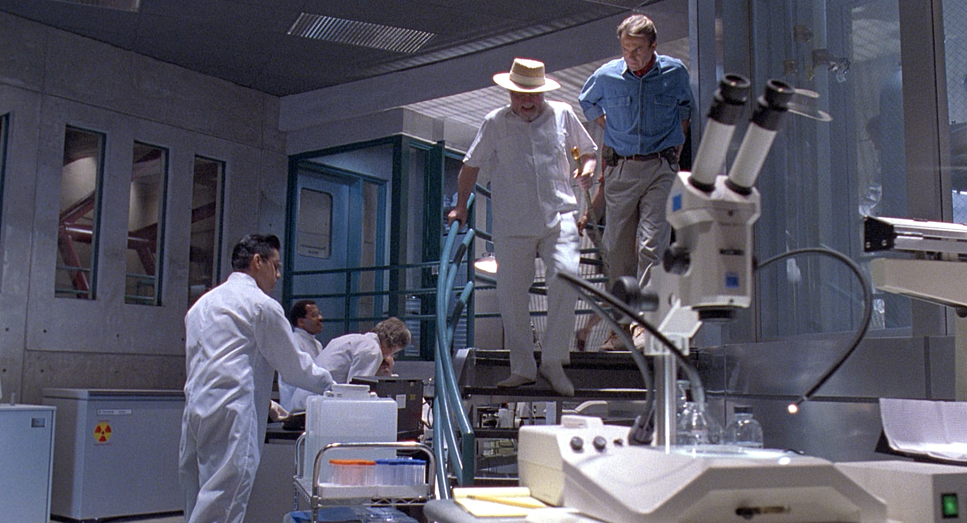

The lighting scheme is a lesson in motivation. For the exterior day scenes, Cundey keeps it high-key and naturalistic—hard sunlight, high contrast, simulating the harsh tropical sun of Costa Rica (filmed in Kauai).

But the night sequences are where the Kodak 5296 EXR 500T film stock really shines. This was a high-speed tungsten stock known for its grain structure and latitude. In the T-Rex rain scene, Cundey used a “motivated” lighting setup. The only “source” is the lightning. He creates a strobe effect where the monster is only visible in flashes of hard, cool light, immediately followed by total darkness. It hides the CGI limitations and ramps up the fear factor. The highlight roll-off on the wet skin of the animatronic, captured on film, gives it a slimy, organic texture that digital sensors often render too cleanly.

Lensing and Blocking

Cundey favored Panavision Primo Primes, often leaning on the wider end of the focal length spectrum. Wide lenses exaggerate depth. If a T-Rex steps three feet closer to a wide lens, it seems to grow twice as large. It makes the environment feel vast and the humans feel small.

The blocking is essentially a game of chess. In the kitchen scene with the raptors, the camera height drops to the eye level of the children. The blocking uses the stainless steel tables as a grid, turning the scene into a stealth mission. The characters are physically hemmed in by the set design. Notice the power dynamics: when Hammond is in control, he is framed traditionally. After the park fails, he is often shot from high angles, diminishing his stature.

Color Grading Approach

From my perspective as a colorist, the “look” of Jurassic Park is a testament to photochemical timing—the predecessor to modern digital grading. The colorist, Dale Caldwell, did a phenomenal job of hue separation.

The palette is cool and desaturated, specifically in the shadows, but the skin tones are kept remarkably clean. This separation is vital. If the skin tones had bled into the lush greens of the jungle, the image would turn to mush. Instead, the characters pop against the background.

The contrast curve is also aggressive. Modern HDR grading often tries to dig details out of the shadows, but here, the blacks are crushed. In the night scenes, if there isn’t light, it is pitch black. This “toe” of the film curve creates true obscurity. The fear comes from what you can’t see. The transition from the highlights (flashlights, flares) to those crushed blacks is smooth, thanks to the chemical response of the film stock. It has a density and weight that gives the image a “thick” feeling.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Jurassic Park: Technical Specs

| Genre | Adventure, Science Fiction, Technology |

|---|---|

| Director | Steven Spielberg |

| Cinematographer | Dean Cundey |

| Production Designer | Rick Carter |

| Costume Designer | Sue Moore, Eric H. Sandberg |

| Editor | Michael Kahn |

| Colorist | Dale Caldwell |

| Time Period | 1990s |

| Color | Cool, Desaturated, Blue |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.85 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, High contrast |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light, Practical light |

| Story Location | Central America > Isla Nublar |

| Filming Location | Hawaii > Kauai |

| Camera | Panavision Panaflex Platinum, Panavision Panaflex Gold |

| Lens | Panavision Primo Primes |

| Film Stock / Resolution | 5245/7245 EXR 50D, 5248/7248 EXR 100T, 5296/7296 EXR 500T |

We talk a lot about the CGI, but the seamless integration came down to Cundey matching the lighting of the live-action plates to the computer graphics. He used stand-ins and rigorous measurements to ensure that the light hitting the actor matched the light hitting the digital raptor.

They shot on 35mm film (specifically 5245 50D for day and 5296 500T for night). The grain of the film helped blend the CGI. Digital renders in 1993 were almost too clean; the film grain acted as a texture layer that glued the fake dinosaur to the real background plate. It’s a reminder that technology is only as good as the technician using it.

- Also read: FINDING NEMO (2003) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: KILL BILL: VOL. 1 (2003) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →