Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) is a reset button for my eyes. It’s three hours of grueling, essential storytelling about the Nazi judges on trial, but visually, it’s a masterclass in how to hold an audience’s attention without a single splash of color. It proves that if your values and composition are solid, you don’t need teal and orange to make an image stick.

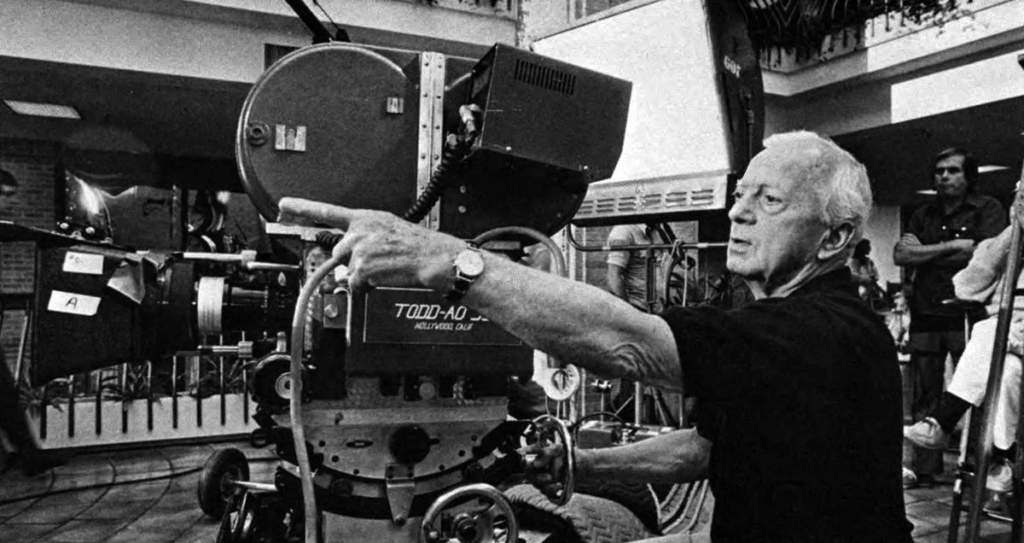

About the Cinematographer

The eye behind the viewfinder was Ernest Laszlo, ASC. If you study his filmography, you realize Laszlo wasn’t interested in being flashy; he was interested in “invisible cinematography.” He understood that for a script this heavy where words are the weapons the camera needed to be a precise, unblinking observer.

Laszlo brought a certain European elegance to Hollywood. His collaboration with Kramer wasn’t about creating pretty pictures; it was about creating a container for the moral weight of the story. He knew exactly when to step back and let the lighting do the talking, sculpting an environment that felt less like a movie set and more like a courtroom where history was actually happening.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Filming this in 1961, just 16 years after the war ended, meant the wounds were still incredibly fresh. Shooting in black and white was a distinct artistic choice here color film was readily available, but I believe Laszlo and Kramer knew that color would have been too distracting, perhaps even too “Hollywood.”

They needed grit. The visual inspiration feels ripped straight from photojournalism and the newsreels of the era. One of the most harrowing sequences in the film involves the screening of actual liberation footage from the concentration camps. That footage is raw, grainy, and high-contrast. The cinematography of the narrative scenes had to bridge the gap to that documentary footage. If the movie had been polished and colorful, that transition would have felt jarringly fake. Instead, the “bomb-scarred” texture of the film stock unifies the drama with the reality, creating a somber historical record rather than just entertainment.

Camera Movements

In modern filmmaking, we are terrified of boring the audience, so we keep the gimbal moving constantly. Judgment at Nuremberg has the confidence to stay still. The camera work is incredibly disciplined.

When the camera does move, it’s usually a slow, psychological push-in. It reminds me of how we use dynamic zooms in post today, but here it’s organic. Watch the testimony scenes: the camera starts wide, establishing the isolation of the witness, and then imperceptibly creeps in. It tightens the screw on the audience. During Spencer Tracy’s closing monologue, the camera just holds. It trusts the actor. It’s a lesson in restraint proving that a static frame, held for 30 seconds, can generate more tension than a hundred rapid-fire cuts.

Compositional Choices

Laszlo treats the courtroom frame like a chessboard. He utilizes deep focus (likely stopping down to a T4 or T5.6) to keep multiple layers of the trial in sharp relief simultaneously.

You’ll often see a composition where the defendant is in the foreground, but the judges are looming sharp in the background, or vice versa. This isn’t just nice framing; it’s narrative efficiency. It connects the accuser and the accused in the same visual space without needing to cut back and forth. I also love his use of negative space. He frequently isolates Burt Lancaster’s character, Dr. Ernst Janning, in a wide frame with empty air around him. It visually reinforces his silence and his separation from the other defendants before he even utters a word.

Lighting Style

This is where the “Colorist” eye really kicks in. The lighting isn’t just “dramatic”; it’s a study in ratios. Laszlo uses what we’d call a high key-to-fill ratio. He isn’t afraid to let the shadow side of a face drop into almost pure black.

It’s motivated chiaroscuro. The light sources feel diegetic streaming in from the high courtroom windows but they are shaped meticulously to create “Rembrandt patches” on the actors’ cheeks. This modeling gives the faces a 3D quality that flat lighting just kills.

What strikes me most is the “hardness” of the light. Modern cinematography loves big softboxes and diffusion, but here, the light is often hard and unforgiving. It casts sharp nose shadows, emphasizing the texture of the skin, the sweat, and the age of the characters. It feels like the harsh light of truth there is nowhere to hide in this courtroom.

Lensing and Blocking

Technically, it looks like Laszlo stuck mostly to focal lengths between 35mm and 50mm the “normal” range that mimics the human eye. He avoids wide-angle distortion which would make the courtroom feel like a caricature. By keeping the focal length grounded, the space feels real.

The blocking is a silent choreography. Spencer Tracy is almost always centered, acting as the moral fulcrum of the image. Maximilian Schell, on the other hand, is blocked dynamically pacing, invading people’s personal space, constantly changing his position in the frame. The lens choice and blocking work together to tell you who is stable and who is volatile, long before the dialogue confirms it.

Color Grading Approach

People often ask me how I “grade” black and white footage since there’s no color to manipulate. The answer is that you stop looking at the vectorscope and start living in the waveform monitor.

If I were grading Judgment at Nuremberg in DaVinci Resolve today, I wouldn’t be touching the Lift/Gamma/Gain wheels in the primaries. I’d be working almost entirely with Custom Curves. The beauty of this film is in the “toe” and the “shoulder” of the curve.

- The Toe (Shadows): The blacks are crushed in the deepest shadows to ground the image, but there is just enough detail in the dark suits to see the texture.

- The Shoulder (Highlights): This is the holy grail of film emulation. The highlights on the skin don’t clip harshly to white; they roll off smoothly. This is that creamy, analog retention that digital sensors struggle to mimic without a good Film Print Emulation (FPE) LUT or DCTL.

Laszlo likely used colored glass filters on the lens (like a yellow or red filter) to separate the tones before the light even hit the film. As a colorist, I view this as “analog channel mixing” manipulating how blue skies or red skin tones map to grey values.

Technical Aspects & Tools

We have to respect the gear they hauled to get these shots. They were likely using the Mitchell BNC, a massive, blimped camera that weighed a ton. You don’t do “run and gun” with a Mitchell. That physical weight dictates the stately, solid feel of the shots.

For film stock, they were almost certainly pushing Kodak Double-X 5222 (or its predecessor). That stock is legendary for a reason. It has a distinctive grain structure that gives the image a “bite.” In the digital age, we often add grain overlays to try and replicate this feeling, but nothing beats the organic dance of silver halide crystals.

The lighting package would have been hot, heavy tungsten Fresnels. Managing the heat and the power for those lights in a set that size is a logistical feat on its own. The result is an image that feels sculpted, intentional, and timeless. It reminds me that while I love my color grading tools, the most important “node” in the chain is always the cinematographer’s choice of where to put the lamp.

- Also read: COME AND SEE (1985) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: HAMILTON (2020) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →