Few films embody that raw, unvarnished reality quite like “Hoop Dreams” (1994).

This isn’t just a “sports doc.” It’s an epic. Seven years of production, following Arthur Agee and William Gates from the hopeful playgrounds of Chicago to the crushing “weeding out” process of elite athletics. When I revisit it, I’m not looking for “pretty” shots. I’m looking for the “ugliest, most beautiful reality” a phrase from the film that perfectly describes its aesthetic. It doesn’t scream for your attention. It just whispers: Look. This is real.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The “look” of Hoop Dreams wasn’t born in a boardroom; it was born in the dirt. Originally intended as a three-week PBS short about streetball, it evolved into a seven-year odyssey as Steve James and his team realized the story was much bigger than a few jumpshots.

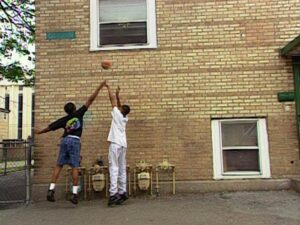

The inspiration was the contrast. You see it everywhere: the cramped, dimly lit homes in Cabrini Green versus the sterile, clinical hallways of St. Joseph’s. The inspiration was the sweat on the concrete. There was no room for artifice here. The camera had to be a silent confidante, sometimes even an uncomfortable witness. This is a lesson for all of us: sometimes the story is so potent, the best thing you can do is just… point the camera and have an empathetic heart.

About the Cinematographer

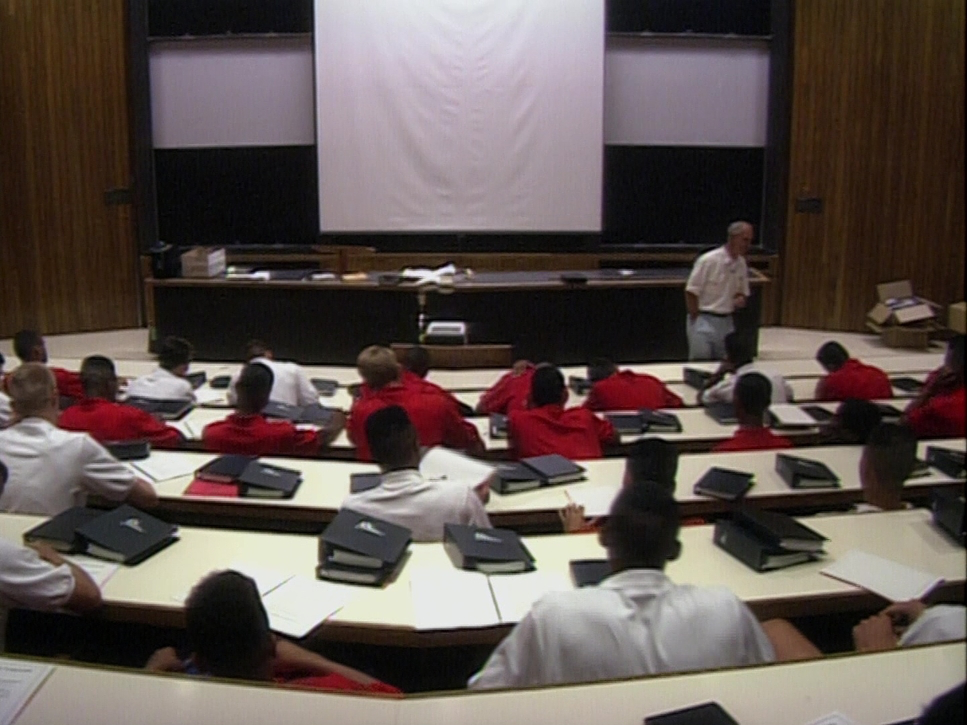

Steve James and Peter Gilbert weren’t just “operating” a camera. In a traditional narrative, you have a shot list and a coffee break. Not here. For seven years, they became extensions of the Agee and Gates families.

Think about that timeline. Seven years. Their craft was about building trust. They weren’t just filming a story; they were living it alongside Arthur and William. It required an insane amount of patience and the ability to capture fleeting moments of despair without ruining the moment. Their cinematography isn’t about virtuosity it’s about an unyielding commitment to being there.

Lensing and Blocking

In the world of immersive documentary, “blocking” is a total misnomer. The subjects aren’t actors; they’re people living their lives. So, the “blocking” is really the cinematographer’s intuition knowing where to stand before the action happens.

Lensing: They relied heavily on versatile zooms (likely 16mm equivalents of a 25-250mm). As a colorist, I can see why. You need to be fast. One second you’re capturing a wide shot of a bustling court; the next, you need a tight close-up on a mother’s face. You can’t stop to swap primes. The lenses were chosen for utility and speed, prioritizing the shot over “optical perfection.”

The Vibe: The blocking was a “dance of reality.” On the court, they were under the basket, reacting. In the homes, they were respectful but intimate. It’s a reactive style that makes the audience feel like a participant, not a spectator.

Camera Movements

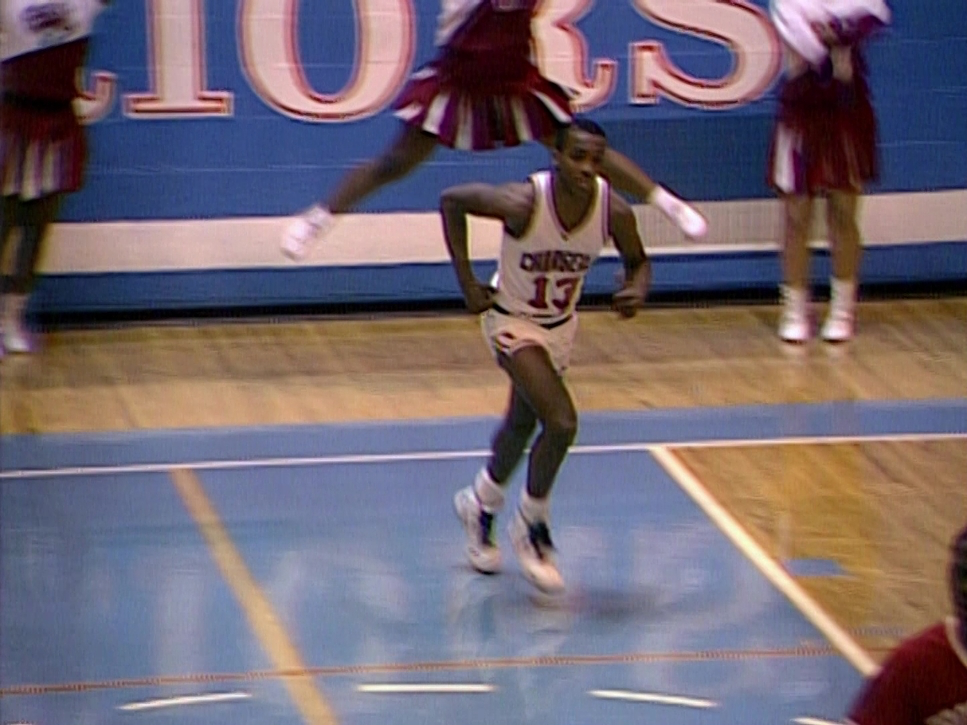

Forget the cranes and dollies. Hoop Dreams is a handheld masterclass.

Handheld provides an immediacy that a tripod just can’t touch. When Arthur is driving to the hoop, the camera is right there, breathing with him. The micro-adjustments and the natural sway mirror the rhythm of the game itself. It’s not about “smooth” Steadicam shots designed to impress. It’s about energy. Off the court, the pans and tilts are reactive following a gaze or a sudden shift in a dinner-table argument. It tells you, without words, that this is happening now.

Lighting Style

On a doc budget, elaborate lighting isn’t an option. Hoop Dreams is all about motivated lighting. It’s raw. It’s honest.

The lighting mirrors the struggle. In the Agee and Gates homes, the light comes from practicals lamps, TVs, or whatever filters through the windows. There’s a gut-wrenching moment where the electricity is cut off at the Agee home. The darkness in those frames tells you more about poverty than any dialogue ever could.

In the gyms, you’ve got that classic, unforgiving fluorescent glow. As a colorist, I see the green-spike in those old lights, but it works. It highlights the sweat. It’s not flattering, but it’s true. They worked with available light, accepting “crushed” blacks and “blown” highlights because getting the moment was more important than the histogram.

Compositional Choices

The composition here feels intuitive. It’s not about the rule of thirds; it’s about the “dance.”

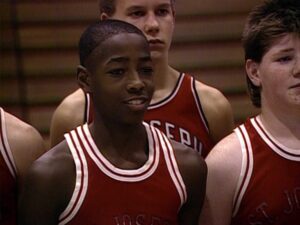

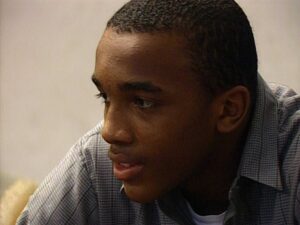

The filmmakers love natural framing peeking through a doorway to catch a private family moment or framing the boys against the crowded sidelines of a gym to show the pressure they’re under. We see tight close-ups that capture Arthur’s ambition or William’s quiet frustration. Then, we get the wide shots of the Cabrini Green projects huge, indifferent structures that make the boys look small. It’s a visual juxtaposition: individual dreams versus systemic challenges. The “imperfections” a subject slightly off-center or a momentary obstruction actually make it feel morereal.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Hoop Dreams (1994) | Technical Specs

| Genre | Action, College, Documentary, Family, Hood, Sports, Drama, Coming-of-Age |

| Director | Steve James |

| Cinematographer | Peter Gilbert |

| Editor | William Haugse, Steve James, Frederick Marx |

| Colorist | Robert Jung, Allen Kelly, Craig Leffel, Oscar Oboza Jr. |

| Time Period | 1990s |

| Color | Saturated, Red, Yellow |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.33 – Spherical |

| Format | Tape |

| Lighting | Soft light, Top light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Overcast, Artificial light |

| Story Location | Illinois > Chicago |

| Filming Location | Illinois > Chicago |

Shooting for seven years in the late 80s and early 90s was a logistical nightmare.

Cameras and Stock: While they used 16mm film (like the Arriflex SR) for that rich, theatrical look, they also leaned on professional tape formats for the longer hauls. This blend creates a heterogeneous texture sometimes grainy, sometimes “thick” with that 90s video look. They likely used Kodak film stocks, pushing them in development to get extra sensitivity in low-light situations.

Sound: You can’t ignore the audio. High-quality external recorders and lavaliers were essential. The squeak of sneakers on the floor and the Chicago city noise are just as important as the visuals in grounding this story.

Editing: They had 250 hours of footage. Think about that. Distilling that into three hours without modern NLE software is a miracle of organization and storytelling.

Color Grading Approach

This is where I get geeky. Hoop Dreams happened way before the era of DaVinci Resolve and digital intermediates. The “grade” was a mix of film stock choice and telecine operators working their magic during the transfer to tape.

The Palette: While the environments are gritty, there’s a surprising saturation in the reds and yellows the colors of the jerseys and the heat of the courts. I love how these primaries pop against the gray Chicago streets. It gives the film a pulse.

The Texture: From my seat in the grading suite, I see the limitations of the 90s technology, and I love them. The blacks aren’t “clean” they’re textured. The highlight roll-off is organic. There’s no “teal and orange” here. Skin tones are the priority. They kept it natural, avoiding aggressive hue separation. The “grade” is honest and unobtrusive. It’s a reminder that sometimes the best “look” is no look at all just the truth, unflinchingly captured.

Hoop Dreams (1994) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from Hoop Dreams (1994) . Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA (1929) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: A MAN ESCAPED (1956) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →