Ex Machina (2015) is at the top, It’s a film that demands you look closer a piece of “hard” sci-fi that uses its visual language with a clinical, almost predatory focus to explore what it actually means to be “human.”

For me, dissecting the visual DNA of this film isn’t an academic exercise; it’s a deep dive into how we, as creators, use glass, light, and sensors to build a world that feels both pristine and terrifyingly sterile. Alex Garland’s directorial debut is a masterclass in restraint, proving that the most impactful cinematography often comes from what you don’t show.

About the Cinematographer

The visual architect here is Rob Hardy BSC. If you follow his work, you know he has this incredible knack for blending raw naturalism with a very structured, high-concept artistry. Hardy doesn’t just “light a scene”; he creates an atmosphere that feels grounded in reality while simultaneously feeling slightly “off-world.”

He is the kind of collaborator who clearly digs into the philosophical marrow of a script. His aesthetic in Ex Machinaleans into a clean, minimalist look, but it never feels empty. Instead, that minimalism serves to amplify every micro-expression and every shift in light. It’s a style that forces the audience to be patient, rewarding them with a level of intimacy that feels almost intrusive.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Ex Machina: Technical Specifications

| Genre | Artificial Intelligence, Cyberpunk, Drama, Science Fiction |

| Director | Alex Garland |

| Cinematographer | Rob Hardy |

| Production Designer | Mark Digby |

| Costume Designer | Sammy Sheldon |

| Editor | Mark Day |

| Colorist | Asa Shoul |

| Time Period | Future |

| Color | Cool, Green, Cyan, Blue |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.39 – Anamorphic |

| Format | Digital |

| Lighting | Soft light, Low contrast |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Story Location | Europe > Scandanavia |

| Filming Location | Norway > Valdall |

| Camera | Sony F55, Sony CineAlta F65 |

| Lens | Cooke Xtal Express, Kowa Cine Prominar, Angenieux Optimo Zooms |

While many assume a film this “clean” was shot on an ARRI system, Hardy actually opted for the Sony F65 and F55. As a colorist, I love this choice. The F65’s 8K sensor provides a level of resolution and “digital purity” that perfectly fits Nathan’s high-tech obsession. It captures a staggering amount of detail, which is vital when you’re trying to sell the intricate, mechanical textures of Ava’s body.

But here is the “human” touch: they paired that ultra-sharp digital sensor with vintage glass specifically Cooke Xtal Express and Kowa Cine Prominar anamorphic lenses. This is a classic “pro move.” By using older, anamorphic glass on a high-res sensor, Hardy introduces subtle imperfections, unique bokeh, and a gentle roll-off that prevents the image from looking too “video-ish.” It creates a tension between the futuristic tech of the story and the organic, cinematic history of the lenses.

Lensing and Blocking

The choice of anamorphic lenses is central to how we perceive the space. Anamorphics inherently distort the edges of the frame and create a specific sense of depth, which Hardy uses to emphasize the isolation of the Juvet Landscape Hotel. Even in wide shots of the Scandinavian wilderness, the framing makes the characters feel minuscule trapped by the very landscape they’re supposed to be “escaping” into.

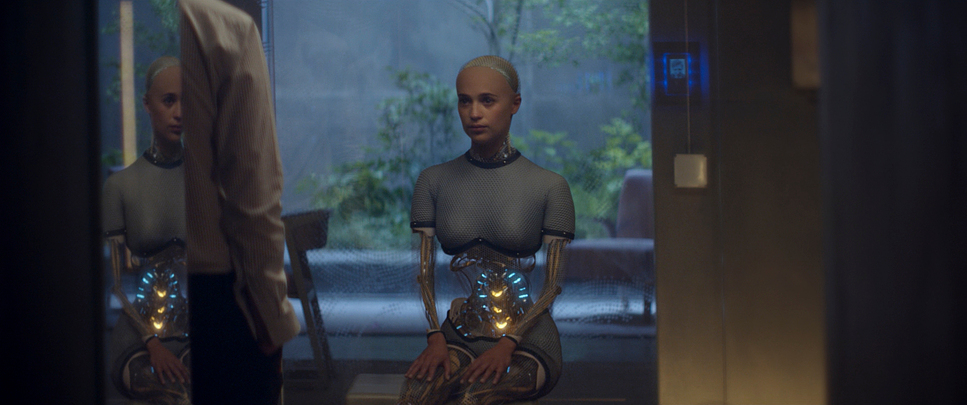

The blocking is exceptionally deliberate, almost like a stage play. Characters are positioned to articulate power dynamics in every frame. Nathan usually dominates the vertical space, while Caleb is often “boxed in” by the architecture. The glass partition in Ava’s room serves as the central axis for the entire film. Hardy and Garland use it to create a physical and emotional barrier that never lets you forget: this is an experiment, not a conversation.

Lighting Style

The lighting in Ex Machina is a study in motivated illumination. Hardy leans heavily into the natural light flooding through the hotel’s massive glass walls. You see the shift from the cool, blue-ish morning light to the warmer, golden hues of the afternoon. But as any DP will tell you, “natural” light requires a lot of work.

Hardy meticulously flags and diffuses that light to sculpt Ava’s form. Because she is partially translucent, the light has to do two things at once: reveal her internal mechanics and keep her feeling like a “character” rather than a prop. Inside the windowless generator rooms or the lab, the lighting shifts to a colder, more clinical artificiality. This dichotomy the serenity of the Norwegian woods vs. the harsh, recessed LEDs of the lab is the visual heartbeat of the film.

Color Grading Approach

This is where I really nerd out. The grade, handled by Asa Shoul, is a masterclass in tonal separation. The palette is dominated by “high-tech” colors: cyans, deep blues, and desaturated greens. However, the real magic is in the skin tones.

In a lesser grade, the cool tones would wash out the actors, making them look like part of the furniture. Here, the skin tones are protected with surgical precision. There’s a warmth in Caleb and Nathan’s faces that provides a necessary “organic” contrast to the cold, concrete environment. As a colorist, I’m looking at the shadow density the blacks are deep and rich, creating a sense of mystery, but they never “crush” the detail. The highlight roll-off on the reflective glass surfaces is incredibly smooth, likely a result of the F65’s dynamic range combined with a very tasteful film-print emulation in the ODT (Output Device Transform).

Compositional Choices

If you want to understand this film, look at the negative space. Hardy uses the minimalist architecture to dwarf the human figures, making them look like specimens under a microscope. But the MVP of the composition is the “looking glass” motif.

Characters are constantly framed through reflections or glass barriers. This creates a sense of surveillance—you never feel like you’re just “watching” a scene; you feel like you’re “monitoring” it. For me, this is a personal inspiration. As filmmakers, we’re always looking for ways to externalize internal states. Using a simple reflection to show Caleb’s growing existential crisis is much more powerful than any line of dialogue. It’s about making every pixel count and using the frame itself as a tool for psychological inquiry.

Camera Movements

The camera in Ex Machina is an observer. It’s rarely handheld; the movements are slow, precise, and motivated. There’s a distinct lack of “fluff.” When the camera moves, it’s usually a slow push-in that acts like a magnifying glass, forcing us to scrutinize Ava’s face for any sign of a “soul.”

The stillness of the camera mirrors the clinical nature of the Turing test. However, when Nathan has his erratic, drunken outbursts (like the famous dance scene), the visual energy shifts. Those jarring moments of movement break the controlled “perfection” of the rest of the film, reminding us that Nathan for all his genius is a volatile, animalistic human. It’s a brilliant use of pacing through camera movement.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The core of the visual inspiration seems to be the “missing God” allegory. The film takes place over seven days (a nod to Genesis), and the setting is a literal “Garden of Eden” for the digital age.

Visually, this translates into a world that is meticulously controlled. The Juvet Hotel isn’t just a backdrop; it’s a character. The vast glass walls act as both a bridge to nature and a barrier against it. This “looking glass” concept, pulled from Lewis Carroll, is the North Star for the cinematography. Every frame asks the same question: Are we seeing a reflection, or a true self? By anchoring these heavy philosophical ideas in consistent visual motifs, Hardy makes the abstract feel palpable.

Ex Machina (2015) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from EX MACHINA (2015). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: HARRY POTTER AND THE DEATHLY HALLOWS: PART 1 (2010) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: ZODIAC (2007) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →