Most submarine movies make the same mistake: they treat the vessel like a stage set. You get the ping of the sonar and the periscope shot, but you never really feel the weight of the water. Das Boot is the exception. It doesn’t just show you the U-boat; it traps you inside it.

Spending my days grading footage at Color Culture, I look at images through a technical scope, analyzing curves and color spaces. But Das Boot is one of those rare films that forces you to stop analyzing and start feeling. It is a lesson in how cinematography can physically exhaust the audience. Siskel and Ebert called it a “technical marvel,” but it’s more than that—it’s a masterclass in claustrophobia. It bypasses the usual “pro-war vs. anti-war” debate by shoving you into an oversized steel cigar with 40 other men and locking the hatch.

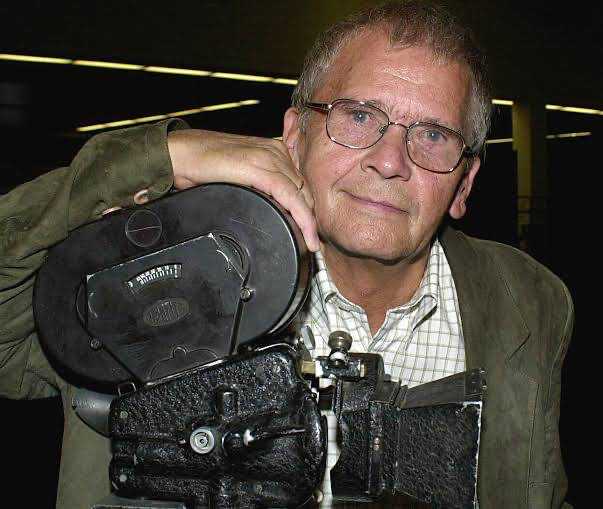

About the Cinematographer

The look of Das Boot was engineered by Jost Vacano. He wasn’t just hired to light a set; he was tasked with solving a physics problem: How do you shoot a cinematic action film inside a tube that is barely wider than a man’s shoulders?

Vacano realized early on that if he shot this traditionally—with static tripod setups—it would feel like a play. To make the audience feel the pressure, the camera had to move. He needed the lens to act as another crew member, squeezing past sailors and ducking under pipes. He didn’t just film a submarine; he helped craft a breathing, groaning metallic beast that served as home, prison, and tomb. His commitment to this tactical realism, supported by an actual U-boat commander as a consultant, is why the film still holds up forty years later.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The visual philosophy here was simple: strip away the glory. In 1981, U-boat crews were typically depicted in Allied films as faceless villains. Director Wolfgang Petersen and Vacano wanted to show them as they were—conscripted men, covered in engine oil, bored out of their minds, and terrified.

The imagery had to reflect that grit. There is no “hero lighting” here. The inspiration was the harsh reality of a long tour: weeks of not bathing, the smell of diesel, and the psychological toll of waiting for death. Vacano’s work captures the “long periods of boredom punctuated by bursts of terror” perfectly. The camera becomes a conduit for empathy, forcing us to learn the layout of the ship and the mood of the crew, effectively conscripting the viewer into the mission.

Camera Movements

Navigating a U-boat requires a specific kind of choreography, and Vacano’s camera work is relentless. He famously refused to use static master shots. Instead, the camera tracks through the narrow corridors, gliding over machinery and rushing behind characters.

A lot of this feels handheld, but it’s actually a highly specific, stabilized rig Vacano developed himself (a precursor to the Steadicam). When depth charges explode, the camera lurches and shakes, mirroring the panic. It’s not just mimicking reality; it’s translating the feeling of the impact. The brilliance lies in the precision—navigating those tight turns without bumping the walls requires more than brute force; it’s a dance. These tracking shots create a voyeuristic intimacy, allowing us to watch the crew deteriorate physically and mentally without ever breaking the immersion.

Compositional Choices

Vacano turned the limitations of the set into a stylistic weapon. Every frame is composed to remind you that there is no escape. He frequently uses wide-angle lenses, not to show a vista, but to exaggerate the cramped conditions. By placing the lens close to the actors, their faces are slightly distorted, feeling uncomfortably near.

The use of overlapping planes is key. Even in a hallway, Vacano layers the image with pipes, valves, and sweaty bodies. This creates depth in a shallow environment and reinforces the feeling of being hemmed in. There is rarely any “clean” headroom; characters are pushed to the edges of the frame. When the sub dives, the camera tilts with the horizon, disorienting the viewer. These aren’t just cool angles; they are visual metaphors for the crushing pressure outside the hull.

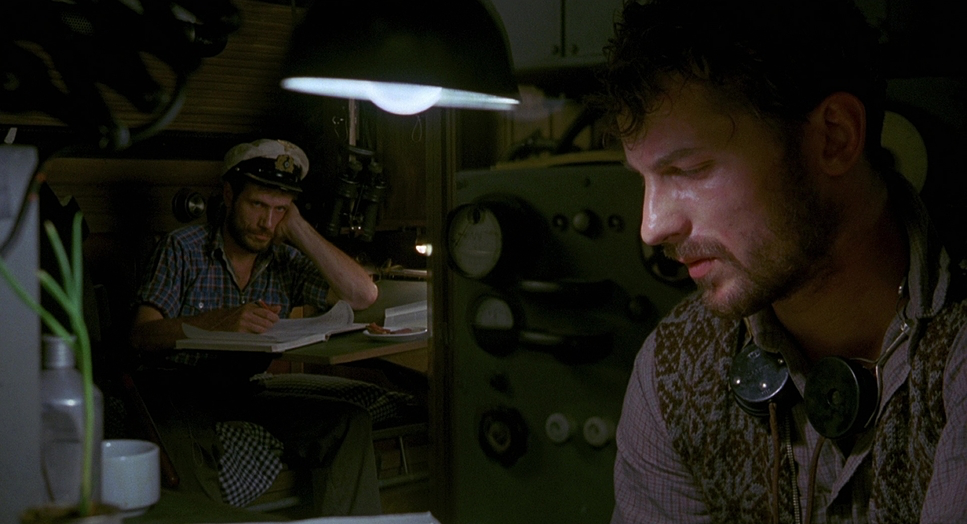

Lighting Style

The lighting in Das Boot is arguably its strongest asset. It is a textbook example of motivated, low-key lighting. Vacano rejected “movie lights” in favor of practicals—if you see a light in the scene, that’s likely what is lighting the shot.

A U-boat is a dark place. Illumination comes from dim overhead bulbs, instrument panels, and the eerie red glow of emergency lights. Vacano lets the shadows crush. Large portions of the frame fall into total darkness, which increases the isolation. He isn’t afraid of “ugly” light; when the crew is exhausted and oily, the light is harsh, highlighting every pore and grease smear. It’s unflattering, and that’s exactly why it works.

Lensing and Blocking

The lensing strategy serves the blocking. Vacano used wide glass to capture the volume of the machinery and the proximity of the men. A telephoto lens would have flattened the space too much; the wide angle makes the walls feel like they are closing in.

But the real genius is the blocking. In a space this small, movement is difficult. The actors aren’t just hitting marks; they are constantly negotiating space with each other. They squeeze, duck, and collide. During the emergency sequences, the “running through the cramped quarters” isn’t faked—the actors are genuinely scrambling over obstacles. Because the camera follows them so fluidly, the audience subconsciously learns the geography of the boat, reinforcing the sensation that we are trapped there with them.

Color Grading Approach

This is where I really geek out. Looking at Das Boot from a colorist’s perspective, it is a study in restraint. Shot on chemically developed 35mm stock, it carries that distinct early-80s print sensibility.

Modern digital grading often tries to separate hues perfectly, but Das Boot leans into the grime. The palette is desaturated and sickly—heavy on industrial greens, rusted browns, and muted blues. It looks damp.

Contrast shaping is crucial to this look. The blacks are deep and inky, giving the image weight, but they retain just enough texture to suggest the machinery hiding in the dark. Hue separation is minimal but effective; skin tones are rendered sallow and ruddy, barely separating from the rusty background. This lack of separation visually blends the men with the machine—they are becoming part of the boat. The highlight roll-off is soft and organic, typical of the film stocks of the era, handling the practical bulbs without the harsh clipping you sometimes see in modern digital formats. It’s a “dirty” grade, and cleaning it up would ruin the movie.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Das Boot (1981) — Technical Specifications

| Genre | Drama, History, War, Military, Submarine, World War II, Political, Epic |

| Director | Wolfgang Petersen |

| Cinematographer | Jost Vacano |

| Production Designer | Rolf Zehetbauer |

| Costume Designer | Monika Bauert |

| Editor | Hannes Nikel |

| Time Period | 1940s |

| Color | Warm, Saturated, Orange |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.85 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, Backlight |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light |

| Story Location | … France > La Rochelle |

| Filming Location | … La Rochelle > La Pallice |

| Camera | Arriflex 35 IIIc |

| Film Stock / Resolution | 8518 Fuji A 250T |

The technical achievement here is massive. They didn’t shoot this on a soundstage with wild walls (removable walls for cameras); they built a full-scale, enclosed replica of a U-boat interior. And they put it on a hydraulic gimbal to actually rock it.

To shoot inside it, Vacano had to innovate. The standard cameras of the time were too bulky, so he stripped down an Arriflex 35mm, modifying it to be small enough to run with handheld. He effectively invented a gyroscope stabilization system to sprint through the tube without the footage becoming unwatchable. They were shooting on high-speed 35mm stock to capture images in the low practical light, pushing the film to its limits. It required immense ingenuity from the lighting team to hide fixtures in such a small space, proving that the best cinematography often comes from solving logistical nightmares.

- Also Read: YOUR NAME. (2016) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also Read: THE LIVES OF OTHERS (2006) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →