Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark (2000) isn’t an easy watch. It polarizes people; you either think it’s a 21st-century masterpiece or you can’t stand the sight of it. For me, it’s a brutal, raw experience where the cinematography acts as a direct, often painful, conduit to Selma’s soul. It’s an emotional gut-punch that uses a stark, dualistic aesthetic to mirror a world that is literally closing in on our protagonist.

About the Cinematographer

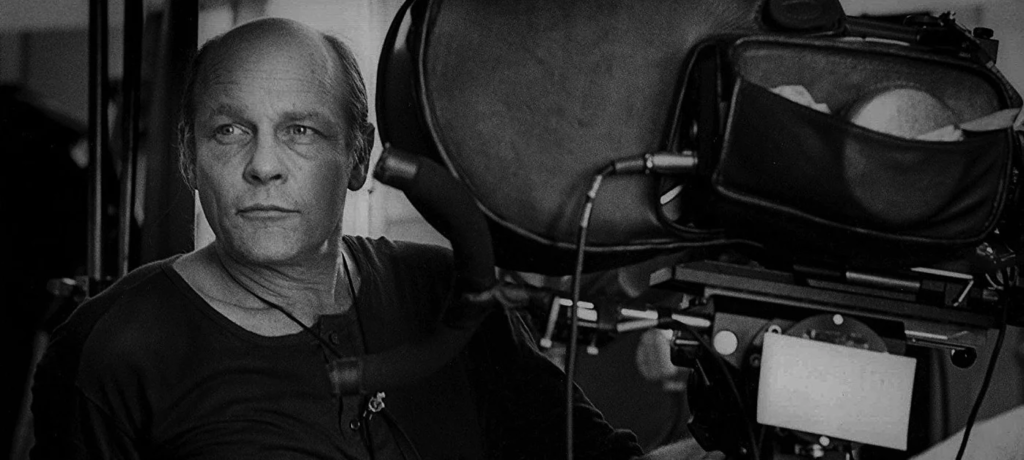

To understand the look of this film, you have to look at the collision between director Lars von Trier and the legendary Robby Müller. Müller is a giant of cinematography (Paris, Texas, Dead Man), but here he had to work within the suffocating constraints of von Trier’s Dogme 95 manifesto. The “Vow of Chastity” meant no special lighting, no filters, and no detached “signature style.”

It’s a fascinating dynamic. You have one of the world’s greatest DPs being told to strip away his toolkit. The result isn’t a lack of vision, but a singular, uncompromising aesthetic where the technical aspects are forced to serve raw storytelling. Müller didn’t just light scenes; he architected a system where handheld operators could capture life as it happened. In our world, we often see directors try to control every pixel, but here, the “unpolished” look was the entire point. It’s a collective effort that feels less like a choreographed film and more like a captured reality.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The visual heart of the film is the wall between Selma’s crushing reality and her vibrant musical fantasies. This isn’t just a metaphor; it’s the literal foundation of how the film was shot. Von Trier and Müller used two completely different visual languages to separate Selma’s mundane existence from her daydreams.

For her daily life, the camera is a restless, almost journalistic observer. It’s handheld, messy, and intentionally “lo-fi.” It feels like a documentary, grounding us in her suffering. You feel every stumble as her vision deteriorates. Then, the film pivots. The musical numbers are steady and fixed. These aren’t just breaks in the story; they are the only moments Selma and the audience can breathe. It’s a fundamental narrative device: one style is a raw nerve, the other is a theatrical refuge.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Dancer in the Dark (2000) — Technical Specifications

| Genre | Crime, Drama, Melodrama, Music, Musical |

| Director | Lars von Trier |

| Cinematographer | Robby Müller |

| Production Designer | Karl Júlíusson |

| Costume Designer | Manon Rasmussen |

| Editor | François Gédigier, Molly Malene Stensgaard |

| Time Period | 1960s |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.35 – Anamorphic |

| Format | Film – 35mm – Cross Process |

| Lighting | Soft light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light |

| Story Location | United States of America > Washington |

| Filming Location | Europe > Sweden |

| Camera | Sony DSR-PD150 Mini DV |

| Film Stock / Resolution | Fuji F-CP 3519 |

The tech setup for Dancer in the Dark was actually groundbreaking for the year 2000. While the narrative scenes were shot on 35mm film (which gave it that organic, grainy grit), the musical sequences took a wild turn. Von Trier famously used over 100 Sony DSR-PD150 MiniDV cameras to shoot the musical numbers simultaneously.

Think about that from a post-production standpoint. You’re mixing 35mm celluloid with consumer-grade digital video. The “low quality” feel of those digital segments wasn’t an accident. The limited dynamic range and the digital noise of the PD150s actually made Selma’s internal world feel more immediate, even if it was less “cinematic” by traditional standards. It’s a masterclass in using the “wrong” tools for the right reasons. They embraced the clipping highlights and the 8-bit limitations to create something utterly unique.

Camera Movements

The movement in this film is its most defining trait. For the narrative, Müller and his team embraced a voyeuristic, handheld approach. This isn’t “shaky cam” for the sake of action; it’s a rough, immediate style that puts you shoulder-to-shoulder with Selma. It’s unpolished and jumpy, prioritizing emotional truth over visual elegance.

The continuous jostling creates a constant sense of unease, mirroring Selma’s vulnerability. It forces you to lean in. Conversely, the musical numbers are almost entirely static. With 100 cameras positioned like security monitors or a stage audience, the movement happens inside the frame. This stillness is a relief. It suggests a world where Selma is finally in control, where the world stops shaking and things finally stay where she puts them.

Color Grading Approach

This is where things get interesting for me. The grading challenge here is immense because you’re dealing with two completely different mediums. For Selma’s reality, which was shot on 35mm and cross-processed, I’d lean into that aggressive, desaturated grit. Cross-processing naturally kicks the contrast and does weird things to the highlights. I’d push for deep, crushed blacks to emphasize her encroaching blindness. A cool, sickly palette lots of greens and muddy blues would help sell that sense of despair.

Then you hit the musical numbers. Because they were shot on MiniDV, you’re working with a much thinner “negative.” My goal here would be to explode the saturation. I’d maximize the primary colors to make the world look hyper-real and dreamlike. We’d lift the shadows to find detail where there shouldn’t be any, infusing the scenes with a warmth that doesn’t exist in her real life. It’s about using every tool to make the transition between the 35mm gloom and the digital “magic” as jarring as possible.

Compositional Choices

Composition in this film isn’t about “pretty” frames; it’s about narrative weight. In the reality segments, the handheld work leads to haphazard, spontaneous framing. Selma is often pushed to the edges or hemmed in by her environment, creating a palpable sense of claustrophobia. The close proximity of the lens collapses the depth of field, making her world feel small and oppressive. It’s a confident rejection of “standard” beauty.

The musical numbers flip the script. The compositions are wider and more balanced, like a stage play. Because the cameras are fixed, the frames are cleaner. They celebrate the space Selma is denied in her daily life. These shots offer a sense of order and harmony, presenting a world where everything finally has its place, even if it’s only happening in her head.

Lighting Style

In keeping with Dogme 95, the narrative lighting is almost entirely naturalistic. We’re talking about available light harsh sun through factory windows or the dim glow of a trailer home. There are no flattering studio setups here. The shadows are deep and unyielding, and the highlights often blow out.

As a colorist, you have to respect that. You can’t try to “fix” the harshness; you have to embrace it. It’s an honest, unvarnished portrayal of her world. When we move to the musicals, the lighting stays “motivated” (often by the factory lights themselves), but it feels different. The way the digital sensors handle the light gives it a softer, heightened quality. It feels purposeful and celebratory, a sharp contrast to the unforgiving glare of her reality.

Lensing and Blocking

The lensing is just as split. For the documentary-style scenes, they mostly used wide-angle lenses on 35mm cameras. This kept the depth of field deep but made the close-ups feel uncomfortably intimate. You aren’t just watching Selma; you’re trapped in her constricted space. The blocking is organic the actors lead and the cameras react. It feels unscripted and raw.

For the musicals, those 100 digital cameras used fixed, wider lenses to capture everything at once. The blocking here is the opposite: it’s highly stylized and choreographed. Performers move through the frame with precision. The camera doesn’t need to move because the “stage” is everywhere. It transforms a drab factory floor into a vibrant theater, allowing Selma to transcend her physical limits for a few minutes.

- Also read: ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN (1976) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: STRANGERS ON A TRAIN (1951) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →