There are those rare masterworks that resonate because every single frame feels like it was dragged out of a deeper truth. Stuart Rosenberg’s Cool Hand Luke (1967) is exactly that. It’s a classic, sure, and the movie that turned Paul Newman into a god, but if you peel back the layers, you find a masterclass in visual storytelling that is as sophisticated as it is raw.

When I sit down with a film like this especially the recent 4K restoration I’m not just watching the plot. I’m dissecting the DNA of the image. This isn’t a standard review; it’s a look at how light, shadow, and a bit of “dirty” chemistry created one of the most unforgettable stories in American film.

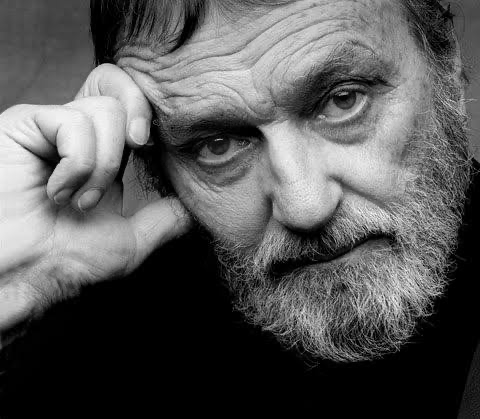

About the Cinematographer

Behind the glass on Cool Hand Luke was the legendary Conrad L. Hall, ASC. If you know his work on In Cold Bloodor Road to Perdition, you know Hall wasn’t a “gloss” guy. He was a pioneer of naturalism who wasn’t afraid to let an image break if it meant finding the truth. He preferred to work with the world as it was, pushing film stocks to their limit to find beauty in the grit.

For Luke, Hall’s style was a perfect marriage with the script’s uncompromising vision. He didn’t just “light” the chain gang; he captured the soul-crushing reality of the Southern sun and the claustrophobia of a bunkhouse. It doesn’t look like a set. It looks like life. That commitment to verisimilitude is why the film still feels so immediate and authentic decades later. Hall didn’t just record the actors; he recorded the atmosphere.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The visual drive here is simple: heat and confinement. The cinematography is an extension of Luke’s struggle the individual versus the machine. I’ve heard people describe this movie as “gritty and dirty,” but as a colorist, I see it as a deliberate aesthetic of discomfort. It’s humid. It’s sweltering. Hall baked that feeling directly into the negative.

Luke is the “World Shaker,” a messianic figure in a place designed to break men. The camera reflects this by oscillating between the bleak, dusty reality of the prison yard and moments that elevate Luke to something mythical. It’s a tricky balance to strike: you have to be brutally honest about the dirt, but you also have to hint at the spiritual. That tension between the sweltering earth and Luke’s reach for something beyond is the bedrock of the entire film.

Camera Movements

Think about the lateral tracking shots of the chain gang. The camera doesn’t glide with high-end stabilization; it feels like it’s working as hard as the men are. It reinforces that endless, mind-numbing cycle of labor. Contrast that with the escape attempts the camera gets frantic, mimicking Luke’s desperation. Then, look at the final shot. The camera ascends at the crossroads, rising above the world. It’s a literal and metaphorical “ascension,” turning a man into a legend. That shift from the grit of the road to a celestial viewpoint is a profound bit of visual punctuation.

Compositional Choices

Conrad Hall used the 2.39:1 anamorphic frame to perfection. He leaned into deep focus, showing us the entire prison environment at once. It makes the place feel inescapable. When you see those vast Florida horizons (actually shot in California, but you’d never know it), they aren’t beautiful they’re cruel reminders of the freedom Luke can’t have.

One of my favorite bits of framing is the visit from Luke’s mother. They are kept apart by the car, a literal and metaphorical barrier. It’s incredibly symbolic; that window represents the chasm his life has created. Then you have the egg-eating scene. Luke is framed almost sacramentally at the center of the table a “Last Supper” for the defiant. The final image of him slumped on the table, arms outstretched in a crucifixion pose, is visual shorthand at its best. It’s not just a “pretty picture”; it’s narrative architecture.

Lighting Style

This is where the film really shines. Hall leaned heavily into hard, naturalistic light. Much of this was shot on location using the searing sun as the primary source, rather than hiding in a controlled studio.

The result? High-contrast, unforgiving imagery. You see deep, black shadows across the faces and highlights glinting off sweat and metal. As a colorist, I love that they didn’t try to “fix” this. The sun is an antagonist in this movie. When the men are digging, that unfiltered daylight isn’t just illumination it’s a weapon. It makes the viewer feel the thirst and the exhaustion. Hall’s lighting is tactile; you don’t just see the scene, you feel the UV index.

Lensing and Blocking

Hall’s lens choices remained functional and grounded. He used the Panavision R-200 with C-series anamorphic glass, which gave the film its signature look. We see wider lenses for the “Extreme Wide” establishing shots to place the men within the vast, rural landscape, while longer telephoto lenses are used to isolate Luke’s iconic, defiant smile.

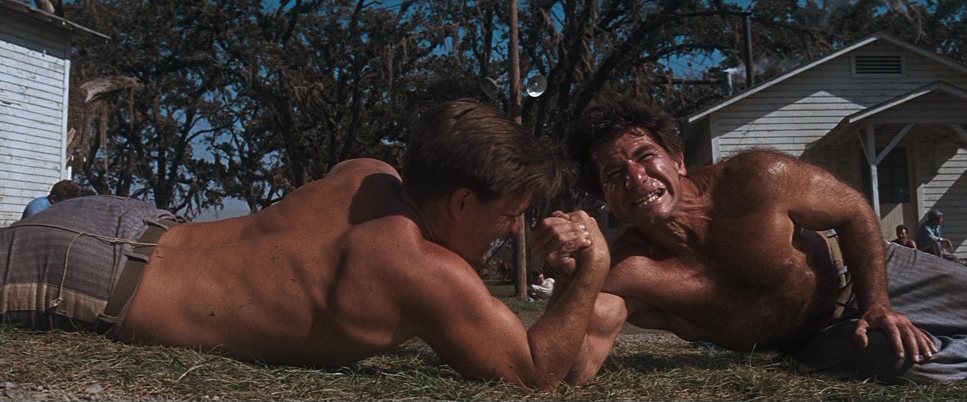

The blocking is just as deliberate. During the boxing match with Dragline, the camera stays low, looking up at Luke. Even as he’s getting pulverized, he looks monumental. In the group scenes, Luke is always the focal point, with the other inmates arrayed around him like a congregation. The way characters are staged tells you everything you need to know about the power dynamics before a single line of dialogue is spoken.

Color Grading Approach

This is my territory. The 4K UHD restoration is a massive leap over the old, compressed Blu-ray versions. Some might complain that it’s “not the cleanest” 4K out there, but they’re missing the point. That “inherent grit” is the soul of the movie.

The new grade leans into a warm, saturated palette lots of ambers and oranges in the skin tones. As a colorist, I wouldn’t change a thing. That warmth amplifies the “humid” feeling of the Florida setting. When you’re grading for HDR, the temptation is to make everything pop, but here, the goal was clearly to preserve the “print-film” sensibility of the 60s. The highlights are rolled off beautifully, keeping detail in the sun-bleached dirt without feeling “digital.” It feels like a vintage Technicolor print earthy, hot, and heavy.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Shooting on 35mm Kodak stock in 1967 meant dealing with real-world limitations. Since so much was shot on location with daylight, the original negative carries all that “uncontrolled” character exposure shifts, natural flaring, and dust.

When Warner Bros. did the 4K scan, they weren’t trying to make it look like it was shot yesterday on an Alexa. They were honoring the source. Their job was to stabilize and clean, but leave the “bones” of the image alone. The 4K transfer respects the Panavision C-series glass and the 35mm grain, giving us the best possible presentation of Conrad Hall’s original intent. It’s a testament to restoration as an act of preservation, not “improvement.”

- Also read: CINDERELLA MAN (2005) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: PLANET OF THE APES (1968) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →