My name is Salik Waquas, and I am the owner of a post-production color grading suite. As a film colorist and enthusiast, I’ve always been captivated by the power of visual storytelling. One film that has particularly intrigued me is Orson Welles’ 1958 classic, Touch of Evil. In this article, I delve into the cinematography of this seminal work, exploring its innovative techniques and enduring influence on filmmakers today.

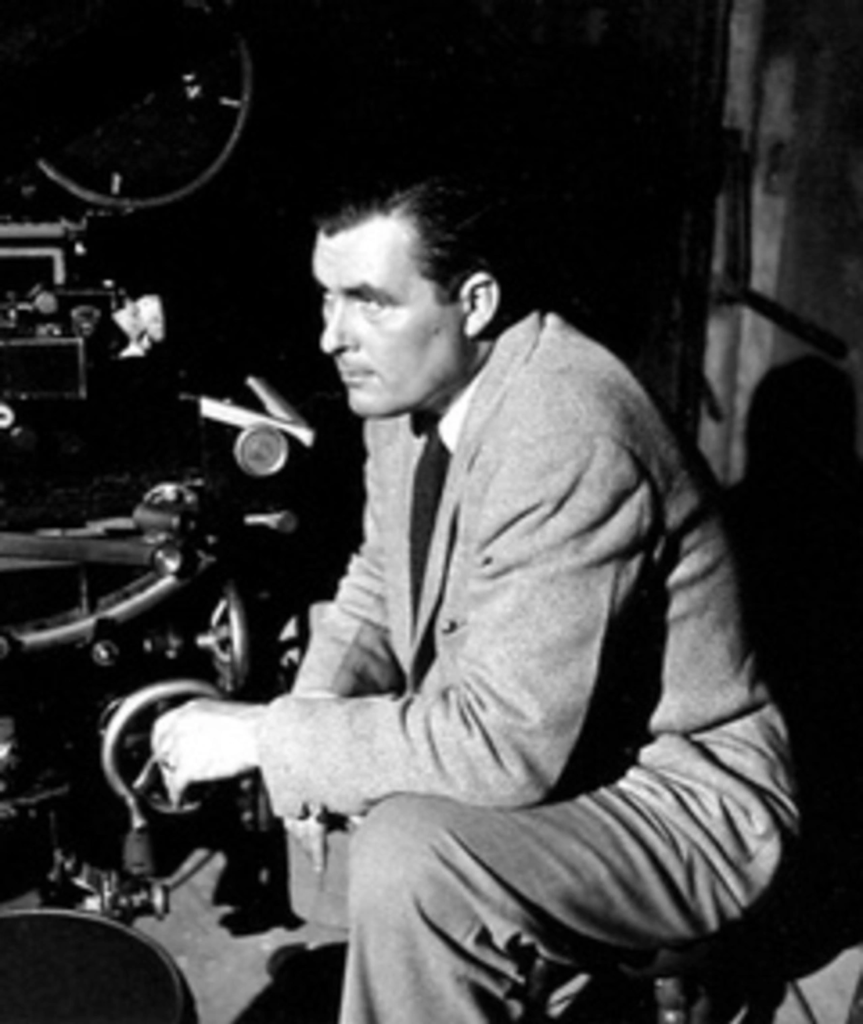

About the Cinematographer

The visual narrative of Touch of Evil was crafted by Russell Metty, a seasoned cinematographer whose career spanned several decades. Known for his work on films like Spartacus and Bringing Up Baby, Metty’s collaboration with Orson Welles marked a defining moment in his career. His ability to balance artistic experimentation with technical mastery was crucial in executing Welles’ ambitious vision. Welles, ever the innovator, relied heavily on Metty’s expertise to push the boundaries of visual storytelling, resulting in a film that remains a benchmark for cinematographers.

Inspiration for the Cinematography of Touch of Evil

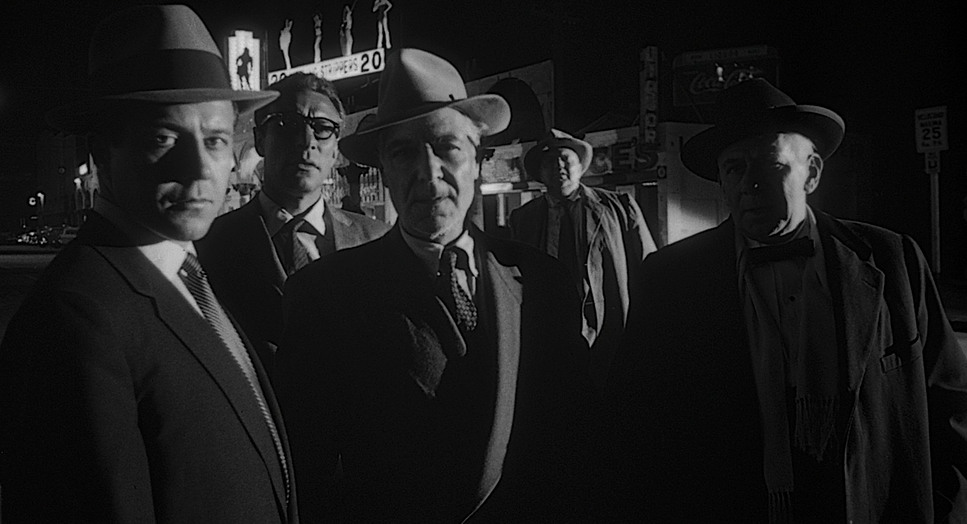

The cinematography of Touch of Evil draws inspiration from German Expressionism and the film noir tradition. The use of stark lighting contrasts, oblique angles, and deep shadows creates an atmosphere of unease and moral ambiguity. This visual language perfectly complements the film’s themes of corruption, moral decay, and the blurred lines between right and wrong. The geographical and symbolic blurring of the U.S.-Mexico border mirrors the characters’ moral ambiguities, and the cinematography emphasizes this fluidity through its stark contrasts and layered compositions.

Camera Movements Used in Touch of Evil

One of the most striking features of Touch of Evil is its dynamic camera movements, which were groundbreaking for their time. The film opens with a three-and-a-half-minute continuous tracking shot that has become one of the most celebrated sequences in cinema history. This single take masterfully establishes the setting, builds suspense, and introduces key characters, all while seamlessly moving through the bustling streets.

While the opening shot garners much attention, Welles himself was particularly proud of a later scene set in the Sanchez apartment. This 12-minute continuous take is a marvel of choreography, requiring precise coordination between actors, camera operators, and lighting technicians. The fluid movement of the camera through the confined space creates a palpable sense of claustrophobia and tension, drawing the audience deeper into the narrative.

Compositions in Touch of Evil

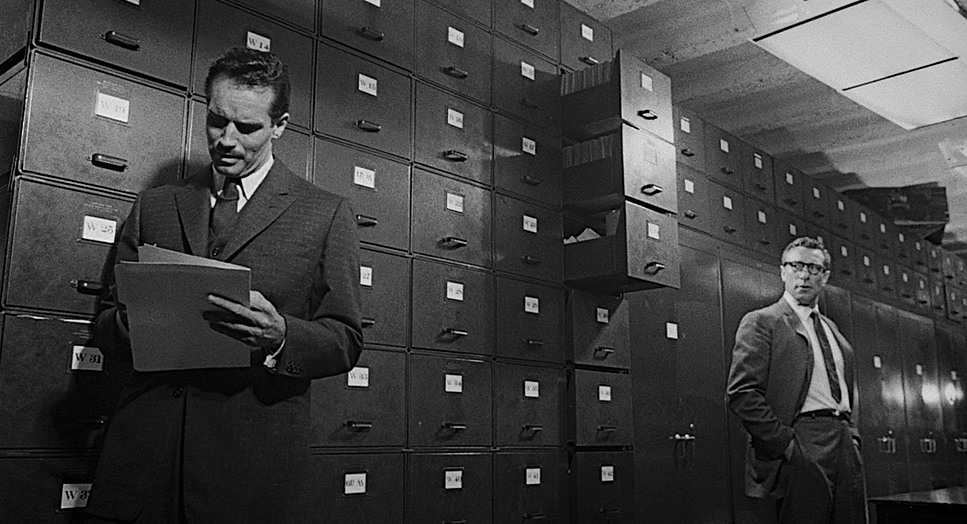

The compositions in Touch of Evil are meticulously crafted to reflect the film’s complex themes and character dynamics. Welles and Metty frequently employed deep focus techniques, allowing multiple planes of action to remain in sharp focus simultaneously. This approach enables intricate staging and layering of visual information, immersing the viewer in the film’s dense atmosphere.

Low-angle shots are used extensively, particularly in scenes featuring the character Hank Quinlan, to emphasize his dominance and moral corruption. These shots make him appear larger-than-life, his presence looming over others within the frame. In contrast, characters like Vargas are often framed to highlight their vulnerability and isolation, reinforcing the power dynamics at play.

Lighting Style of Touch of Evil

The lighting in Touch of Evil is quintessentially noir, characterized by high-contrast setups that create deep shadows and stark highlights. This dramatic use of light and shadow enhances the film’s mood, emphasizing the moral ambiguities and tensions that drive the narrative. Unconventional lighting angles, such as illumination from below or through venetian blinds, cast striking patterns and contribute to the overall atmosphere of unease.

In scenes like the Sanchez apartment, the strategic use of lighting intensifies the claustrophobic feeling. The controlled light sources and deep shadows not only define the physical space but also reflect the psychological states of the characters. Faces are often partially obscured by shadows, adding to the sense of mystery and distrust.

Lensing and Blocking of Touch of Evil

The choice of lenses and meticulous blocking are central to the film’s visual storytelling. Welles and Metty utilized wide-angle lenses, such as 18mm or 21mm, to achieve deep focus and exaggerated perspectives. This allowed for dynamic and layered compositions, where foreground and background elements are simultaneously in sharp focus.

Blocking in the film is carefully orchestrated to maximize the use of space and camera movement. Characters move fluidly within the frame, often entering and exiting in ways that enhance the narrative flow. This precise coordination between actors and camera results in a seamless integration of performance and cinematography, with the movement of characters reflecting their relationships and emotional states.

Color of Touch of Evil

Although Touch of Evil was shot in black and white, the film makes masterful use of tonal range to create a rich grayscale palette. The deliberate control over tonal values enhances the mood and supports the exploration of moral ambiguity within the narrative. Shadows are filled with texture and detail, adding depth to the images and contributing to the film’s immersive atmosphere.

The careful manipulation of light and shadow serves as a substitute for color, with contrasts between light and dark reflecting the film’s central themes. This nuanced approach to grayscale tones elevates the visual storytelling, demonstrating that color is not solely dependent on hue but can be effectively conveyed through tone and contrast.

Technical Aspects of Touch of Evil

TOUCH OF EVIL (1958)

1.85:1 | 35mm Spherical | Bausch and Lomb Baltar

| Genre | Crime, Drama, Thriller |

| Director | Orson Welles |

| Cinematographer | Russell Metty |

| Production Designer | Robert Clatworthy, Alexander Golitzen |

| Costume Designer | Bill Thomas |

| Editor | Aaron Stell, Virgil W. Vogel |

| Time Period | 1950s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.85 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, High contrast, Underlight |

| Lighting Type | Moonlight |

| Story Location | North America > Mexico |

| Filming Location | Los Angeles > Venice |

| Camera | Mitchell BNC |

| Lens | Bausch and Lomb – Original Baltar |

From a technical standpoint, Touch of Evil was groundbreaking for its time. The complex long takes required precise coordination and innovative equipment. The opening tracking shot, for example, involved a combination of crane and dolly movements, utilizing a Chapman Hercules mobile crane to achieve fluid camera motion that would have been impossible with static setups.

The film was shot in the standard Academy aspect ratio of the time, but Welles’ compositions are so meticulously crafted that they translate well even when adapted to wider formats like 1.85:1. The lighting setups for the long takes were feats of ingenuity, with multiple light sources carefully positioned and adjusted throughout scenes to maintain consistent exposure and mood.

The use of wide-angle lenses facilitated the deep focus and dynamic perspectives that are characteristic of the film. This technical choice, combined with Welles’ hands-on approach to set design and lighting, resulted in a visually cohesive and innovative work that pushed the boundaries of what was technically possible at the time.

- Also Read: CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS OF TITANIC (IN DEPTH)

- Also Read: CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS OF THERE WILL BE BLOOD (IN DEPTH)

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →