My name is Salik Waquas, and I am the proud owner of a post production color grading suite where I have dedicated years to perfecting the art and science of visual storytelling. Over the course of my career, I have immersed myself in the technical and creative intricacies of color correction and grading, working closely with filmmakers to bring their visions to life. In this article, I share my personal analysis of the cinematography in Charlie Chaplin’s silent classic, The Gold Rush.

About the Cinematographer

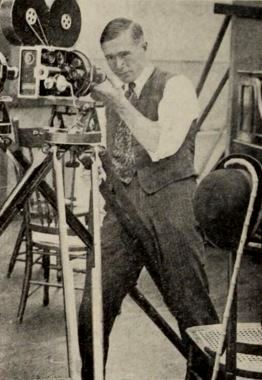

Roland Totheroh may not be a household name like his frequent collaborator Charlie Chaplin, but his impact on the visual language of silent cinema is immeasurable. Working as Chaplin’s long-time cinematographer, Totheroh was instrumental in translating Chaplin’s whimsical and bittersweet narratives into a series of unforgettable images. His deep understanding of light, composition, and movement allowed him to overcome the era’s technological constraints and create visuals that still captivate audiences nearly a century later.

I have long admired Totheroh’s ability to blend technical precision with creative intuition. His collaboration with Chaplin was built on a mutual understanding that every frame could communicate a story as powerfully as any dialogue. This shared vision transformed The Gold Rush into a cinematic masterpiece—a film that combines humor, melancholy, and the raw challenges of survival in a harsh landscape. Through my own journey in the color grading world, I have come to appreciate how Totheroh’s pioneering work laid the foundation for many of the techniques that I employ and innovate upon in my daily practice.

Inspiration for the Cinematography of “The Gold Rush”

The visual inspiration behind The Gold Rush is as fascinating as it is complex. The film draws heavily on the harsh realities of the Klondike Gold Rush, a period defined by the promise of fortune and the brutal realities of survival. Totheroh and Chaplin transformed these historical hardships into a visual narrative oscillating between grim realism and whimsical escapism.

Real-world events such as the infamous Donner Party tragedy and the perils faced by gold prospectors infused the film with a palpable sense of danger. Yet, Chaplin’s genius lay in his ability to balance these dark themes with his signature comedic touch. In my view, this interplay between the stark brutality of nature and the absurdity of human struggle is what gives The Gold Rush its enduring appeal.

Furthermore, Totheroh’s inspiration was not limited to historical realism. He also drew upon German Expressionism, employing exaggerated lighting contrasts and dramatic shadows to heighten emotional impact. This fusion of documentary-style realism with theatrical staging allowed the film to communicate layers of meaning without the need for spoken dialogue—a technique that continues to influence both filmmakers and colorists today.

Camera Movements Used in “The Gold Rush”

One of the most compelling aspects of The Gold Rush is its innovative use of camera movements—a remarkable feat considering the technical limitations of the 1920s. Totheroh’s approach was both subtle and intentional, using camera work not merely to capture the action but to enhance the overall narrative.

Static shots form the backbone of the film’s visual storytelling, allowing the audience to fully absorb the physical comedy and emotive expressions of Chaplin’s performance. Yet, when movement was required, Totheroh did not shy away from employing techniques such as dolly shots and tracking shots. One of the most memorable examples is the scene featuring the precariously balanced cabin teetering on the edge of a cliff. Here, the careful use of camera movement heightens the tension, drawing the viewer into the perilous moment with an almost poetic fluidity.

In my own work as a colorist, I have seen firsthand how subtle camera movements can transform a static scene into a dynamic narrative. The way Totheroh choreographed each shot—whether through a slow, deliberate pan or a carefully executed tracking move—underscores the fact that every frame is an opportunity to deepen the emotional and thematic resonance of the story.

Compositions in “The Gold Rush”

One of the most striking examples of Totheroh’s compositional prowess is the use of negative space. In scenes where Chaplin appears isolated—such as the iconic moment of him standing alone in a bustling dance hall—the vast emptiness of the surrounding space not only emphasizes his solitude but also reinforces the inherent tension between human vulnerability and an indifferent natural world. This technique of juxtaposing a solitary figure against a backdrop of expansive, untouched landscapes is a visual strategy. It serves as a reminder that silence, when framed correctly, can speak louder than words.

Symmetry and leading lines also play critical roles in guiding the viewer’s eye. Whether it’s through the careful placement of characters and props or the strategic use of foreground and background elements, every compositional choice in The Gold Rush is designed to support both comedic timing and dramatic narrative beats.

Lighting Style of “The Gold Rush”

In the snow-covered landscapes, the use of diffused, natural lighting creates a sense of cold isolation, highlighting the harshness of the environment. This choice is particularly effective in scenes where the brilliance of the white snow contrasts sharply with the darker elements of Chaplin’s costume or the looming threat of nature itself. Conversely, interior scenes—such as those set in the warm, bustling dance halls—feature a softer, more inviting illumination. This contrast not only serves to define the spatial and emotional dichotomies within the film but also demonstrates Totheroh’s acute awareness of how light can be used to manipulate mood.

As a colorist, I am continually inspired by Totheroh’s ability to harness natural light. His methods remind me that even in the absence of high-tech equipment, thoughtful manipulation of light and shadow can yield a painterly quality that enriches the narrative. It is this same philosophy that drives my work today, as I strive to recreate the emotional subtleties of a scene through careful color grading and lighting correction.

Lensing and Blocking of “The Gold Rush”

The technical decisions surrounding lensing and blocking in The Gold Rush showcase Totheroh’s remarkable ability to turn limitations into strengths. Working with hand-cranked cameras and fixed focal lengths, Totheroh was forced to be deliberate with every shot—a discipline that has left an indelible mark on the art of filmmaking.

Totheroh often utilized wide-angle lenses to capture the expansive, icy panoramas that define the film’s setting. These lenses not only allowed him to include vast amounts of detail in each frame but also created a sense of scale that magnified both the grandeur of nature and the vulnerability of Chaplin’s character. Medium and long shots were strategically employed to capture the full range of Chaplin’s physical comedy, ensuring that every movement was given the space and context it deserved.

Blocking in The Gold Rush was equally meticulous. Every movement, every entrance and exit from the frame, was choreographed to enhance the narrative’s pacing and timing. A prime example of this is the precise staging of characters during the cabin-on-a-cliff sequence, where even the slightest shift in position amplifies the tension and impending danger. For me, as someone who works at the intersection of technical precision and creative expression, Totheroh’s approach to lensing and blocking is a constant source of inspiration. It is a reminder that every visual element—from the choice of lens to the placement of an actor—must serve the story.

Color of “The Gold Rush”

Although The Gold Rush was originally captured in black and white, its visual impact is deeply rooted in a mastery of tonal contrast and texture that resonates strongly with modern color grading techniques. The film’s original monochrome palette was carefully crafted to emphasize contrast—making Chaplin’s character pop against the stark white landscapes and deep, enveloping shadows.

In later restorations, colorization efforts have introduced sepia tones that evoke a sense of nostalgia while paying homage to the film’s historical context. Yet, it is the original black-and-white imagery that remains a benchmark for technical and aesthetic excellence. The deliberate interplay of light and dark, the balance between shadow and highlight, and the careful attention to texture all contribute to an enduring visual narrative that has influenced countless modern filmmakers and colorists, myself included.

Technical Aspects of “The Gold Rush”

THE GOLD RUSH (1925) – Technical Specifications

| Genre | Adventure, Comedy, Drama, Slapstick |

| Director | Charlie Chaplin |

| Cinematographer | Roland Totheroh |

| Production Designer | Charles D. Hall |

| Editor | Charlie Chaplin |

| Time Period | 1800s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.33 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Story Location | Alaska > Sierra Nevada Mountains |

| Filming Location | USA > California |

Beyond its visual flair, The Gold Rush was a technical marvel in its day—one that pushed the boundaries of what was thought possible in early cinema. The film’s groundbreaking special effects, innovative editing techniques, and practical solutions to on-set challenges all contributed to its status as a cinematic classic.

One of the most remarkable technical achievements in the film is the use of miniatures and matte paintings to create the illusion of a cabin precariously balanced on the edge of a cliff. This sequence, which combines practical effects with clever camera work, not only heightens the dramatic tension but also serves as a testament to Totheroh’s resourcefulness. Despite the absence of modern digital effects, every shot was meticulously planned and executed to convey a sense of real danger and urgency.

The editing in The Gold Rush was equally ahead of its time. With tight cuts and seamless transitions, the film maintains a rhythmic pace that draws the audience deeply into its narrative.

Also Read: Cinematography Analysis Of Yojimbo (In Depth)

Also Read: Cinematography Analysis Of The Seventh Seal (In Depth)

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →