My name is Salik Waquas, and I am a filmmaker and full-time colorist passionate about the power of visuals in storytelling. I own a professional post-production color grading suite where I transform raw footage into cinematic works of art. My fascination with cinematography goes beyond aesthetics; it’s about the emotional impact and narrative depth achieved through the interplay of light, shadow, composition, and color. In this article, I dive deep into the cinematography of Rear Window, a masterpiece by Alfred Hitchcock, to explore how its visual elements elevate the film into an enduring classic.

Cinematography Analysis Of Rear Window

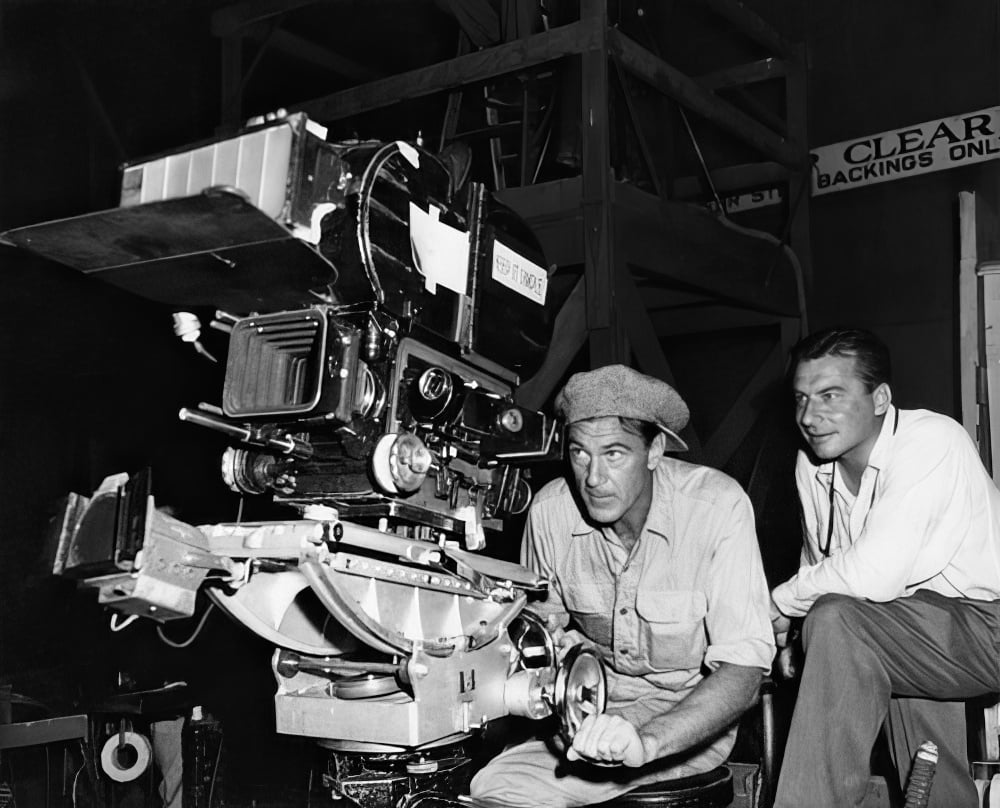

About the Cinematographer

Robert Burks, the genius behind the lens of Rear Window, was a frequent collaborator of Alfred Hitchcock and the cinematographer behind some of his most iconic films, such as Vertigo and To Catch a Thief. Burks was a craftsman who thrived on precision, ensuring that every visual decision served the story. What set him apart was his ability to turn even the most technically complex setups into emotionally resonant images.

In Rear Window, Burks transformed a confined set into a sprawling visual narrative, crafting an entire neighborhood teeming with life. His use of light, shadow, and framing transformed the apartment courtyard into a character in its own right. While some cinematographers rely on visual flair, Burks prioritized utility and immersion, ensuring that every frame deepened the audience’s connection to the story.

Inspiration for the Cinematography of Rear Window

The cinematography of Rear Window was shaped by Hitchcock’s bold decision to restrict the camera to a single location—the protagonist Jeff’s apartment. This confined perspective mirrors Jeff’s own limitation as a wheelchair-bound photographer, creating a shared experience of helpless voyeurism.

This visual constraint was inspired by Hitchcock’s desire to immerse the audience fully in Jeff’s world. The film’s voyeuristic style reflects the Cold War-era themes of surveillance and paranoia. Each window in the courtyard becomes a microcosm of drama, capturing fragmented glimpses of life that mirror Jeff’s own insecurities and fears. These windows act as screens, drawing the audience into a meta-commentary on the act of watching—whether as a voyeur or a film spectator.

Camera Movements Used in Rear Window

One of the most striking aspects of Rear Window is its restrained camera movement. Hitchcock famously preferred subtlety, believing that flashy techniques could distract from the story. Burks followed this philosophy, using slow pans and tilts to mimic the natural motion of the human eye as Jeff surveys the courtyard.

Point-of-view (POV) shots dominate the film, pulling the audience into Jeff’s perspective. These shots create a shared experience, forcing us to observe and interpret events alongside him. For instance, when Jeff’s gaze shifts from Miss Lonely Hearts to Thorwald, the subtle A-to-B camera movement introduces new layers of tension, as the audience pieces together the mystery in real time.

This careful choreography extends to the camera’s inward movements, which remain tethered to the window. Even when the focus shifts to Jeff and Lisa, the connection to the outside world—and Jeff’s voyeuristic obsession—remains visually intact.

Compositions in Rear Window

The compositions in Rear Window are a masterclass in visual storytelling. Hitchcock and Burks treated the courtyard like a theater stage, with each window acting as a narrative vignette. Every frame is meticulously layered to guide the audience’s attention, ensuring that each story unfolds organically within the larger tableau.

Jeff’s perspective of his neighbors is often captured in long shots, emphasizing the physical and emotional distance between him and their lives. This contrasts sharply with the tighter framing used in his scenes with Lisa, where the emotional stakes feel more immediate. The interplay of these framing choices creates a rhythm that keeps the audience engaged with both the mystery and the personal drama.

Lighting Style of Rear Window

Lighting in Rear Window plays an essential role in establishing mood and guiding the audience’s eye. Burks adopted a practical, naturalistic style, mimicking the light sources one might find in an apartment complex—streetlights, sunlight, and interior lamps. Despite its realism, the lighting is carefully controlled to highlight specific moments and characters.

The lighting contrasts between Jeff’s apartment and his neighbors are particularly striking. Jeff’s space is often dimly lit, reflecting his isolation and stagnation, while the neighboring apartments are bathed in light, symbolizing vitality and drama. These contrasts not only create visual interest but also subtly comment on Jeff’s internal state.

One of the film’s most memorable lighting moments occurs when Jeff uses his flashbulb as a weapon. The disorienting bursts of light become a metaphor for exposure—both literal and psychological—as the predator becomes the prey.

Lensing and Blocking in Rear Window

Burks’ lens choices were pivotal in achieving the voyeuristic effect of Rear Window. The majority of the film was shot with a 50mm T2.5 Baltar lens, replicating the natural field of view. For shots simulating Jeff’s binoculars or telephoto lens, Burks used longer focal lengths, such as a 152mm lens, to compress space and create a sense of intimacy.

Blocking was equally meticulous. Characters moved within their apartments in ways that felt natural yet were carefully choreographed to ensure clarity. For example, Thorwald’s slow, deliberate movements amplify his ominous presence, while Miss Torso’s lively dances bring energy to the frame. These choices keep the courtyard visually dynamic, even when Jeff himself remains stationary.

Color of Rear Window

While subtle, color plays a crucial role in Rear Window. The film was shot on Eastman Color Negative film, which offered rich yet realistic tones. Each apartment was designed with a distinct palette to reflect its inhabitant’s personality: Miss Lonely Hearts’ space is suffused with melancholic hues, while Miss Torso’s is vibrant and inviting.

Jeff’s apartment, in contrast, is dominated by muted tones that underscore his detachment from the world outside. Lisa, however, often appears in brighter colors, symbolizing her vitality and the emotional connection she tries to reignite in Jeff. These color contrasts enhance the thematic depth, emphasizing the tension between observation and participation.

Technical Aspects of Rear Window

Rear Window (1954) — Technical Specifications

| Genre | Mystery, Thriller, Psychological Horror, Murder Mystery, Horror, Drama, Crime, Detective |

| Director | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Cinematographer | Robert Burks |

| Production Designer | Hal Pereira, J. McMillan Johnson |

| Costume Designer | Edith Head |

| Editor | George Tomasini |

| Colorist | Richard Mueller |

| Time Period | 1950s |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.66 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Story Location | New York City > Greenwich Village |

| Filming Location | Los Angeles > Paramount Studios |

| Camera | Mitchell BNC |

| Lens | Bausch and Lomb – Original Baltar |

Technically, Rear Window was a marvel of its time. The entire courtyard was constructed on a massive soundstage, complete with functioning apartments and a drainage system for rain scenes. This controlled environment allowed Burks and Hitchcock to manipulate every aspect of the frame with precision.

The film was shot on 35mm using Eastman 25T5248 film stock, with an ISO sensitivity of 50. This required intensely bright lighting setups—up to 17,000 lux—to achieve proper exposure. The resulting images are crisp and detailed, with hard shadows that enhance the film’s noir-inspired aesthetic.

Sound design also plays a significant role. Every noise—from the distant hum of traffic to snippets of conversations—was diegetic, immersing the audience in Jeff’s auditory experience. This attention to realism grounds the film, making its suspense all the more palpable.

Conclusion

As I reflect on Rear Window, I’m struck by how it transforms its technical limitations into artistic triumphs. Hitchcock’s decision to confine the camera to Jeff’s perspective amplifies the suspense and immerses the audience in the narrative. Burks’ cinematography perfectly complements this vision, crafting a world that feels both intimate and expansive.

For me, as a filmmaker and colorist, Rear Window is a constant source of inspiration. Its meticulous compositions, masterful lighting, and innovative use of space demonstrate the power of visual storytelling. It’s a film that invites repeated viewings, each time revealing new layers of meaning and craft. To anyone passionate about cinema, I urge you to revisit this timeless masterpiece—it’s a lesson in how to tell a story without ever leaving the room.

- Also Read: CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS OF PATHER PANCHALI (IN DEPTH)

- Also Read: CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS OF THE THIRD MAN (IN DEPTH)

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →