As a filmmaker and colorist, I’ve always been captivated by the power of visual storytelling. My name is Salik Waquas, and I own a post-production color grading suite where I have the privilege of bringing cinematic visions to life. One film that has profoundly influenced my approach to cinematography and color grading is “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967) directed by Arthur Penn. The film’s groundbreaking visual style not only redefined American cinema but also continues to inspire filmmakers today. In this article, I will share my analysis of the film’s cinematography, exploring how Burnett Guffey’s innovative techniques have left an indelible mark on the art of filmmaking.

Cinematography Analysis Of Bonnie and Clyde

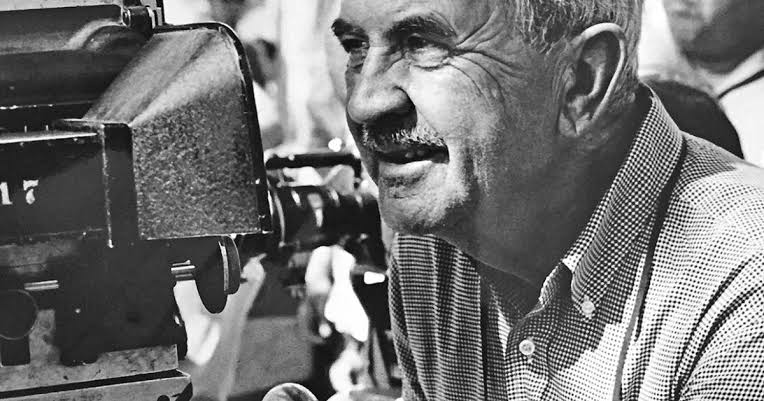

About the Cinematographer

Burnett Guffey, the cinematographer behind “Bonnie and Clyde,” was an industry veteran whose work significantly shaped the film’s groundbreaking aesthetic. Having already won an Academy Award for “From Here to Eternity,” Guffey brought extensive experience in both black-and-white and color cinematography. His ability to blend traditional Hollywood techniques with innovative approaches made “Bonnie and Clyde” a visual masterpiece. His work on the film earned him a second Academy Award, solidifying his legacy as one of Hollywood’s greatest cinematographers.

As a colorist, I find Guffey’s cinematographic approach particularly inspiring. He masterfully mirrored the film’s duality—lighthearted romanticism intertwined with brutal realism—using naturalistic lighting, dynamic compositions, and evocative camera work. His ability to capture the essence of Depression-era America while reflecting the rebellious, free-spirited ethos of the 1960s is a testament to his skill and vision.

Inspiration for the Cinematography of “Bonnie and Clyde”

Guffey drew significant inspiration from the French New Wave, a revolutionary cinematic movement of the 1950s and 1960s characterized by its experimental styles and rejection of conventional filmmaking norms. Director Arthur Penn and Guffey borrowed techniques from filmmakers like François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, incorporating jump cuts, handheld camera movements, and naturalistic lighting into their work. Embracing these unconventional methods allowed Guffey to infuse the film with a sense of realism and immediacy that was rare in Hollywood at the time.

I believe that this bold fusion of French New Wave aesthetics with the rugged Americana of Depression-era settings was both daring and effective. It lent the film an experimental edge that set it apart from the polished, conservative style of traditional Hollywood. The rebellious energy of the New Wave style underscored the anti-establishment themes of the story, resonating with contemporary audiences who were grappling with the countercultural movements of the 1960s.

Camera Movements Used in “Bonnie and Clyde”

Guffey’s camera work in “Bonnie and Clyde” is both dynamic and purposeful, reflecting the energy of its protagonists. He skillfully utilized a mix of static shots and fluid, handheld movements to create a visual rhythm that oscillates between moments of calm intimacy and chaotic violence. During chase scenes and bank heists, the camera often moves frenetically, employing handheld cameras to create a sense of urgency and chaos. This technique immerses the audience in the action, mimicking the adrenaline rush of the characters.

Conversely, during intimate moments, such as Bonnie and Clyde’s conversations, he employed smooth tracking shots and steadier compositions. This contrast in camera techniques effectively balances the film’s high-octane sequences with its more subtle, character-driven moments, allowing the characters’ emotions to unfold naturally on screen.

One standout sequence is the final ambush scene, where the camera switches from wide, contemplative shots to rapid close-ups. This shift mirrors the sudden, brutal end of Bonnie and Clyde’s journey. The fluid transitions and sudden cuts heighten the emotional impact, making the audience feel both the inevitability and the shock of their demise.

Compositions in “Bonnie and Clyde”

The compositions in “Bonnie and Clyde” are meticulously crafted to enhance the storytelling. Guffey often framed the characters against vast, open landscapes of rural America, emphasizing their isolation and the emptiness of their pursuits. These wide shots not only establish the scale of their environment but also mirror the economic struggles of the Great Depression.

He also played with foreground and background elements to create depth within the scenes. One technique that stands out to me is his use of diagonal lines and framing within the frame, which adds a dynamic quality to static shots. Close-ups play an equally important role, particularly in capturing the raw emotions of the characters. Guffey frequently frames Bonnie and Clyde in tight two-shots, symbolizing their inseparable bond. These intimate compositions are contrasted with group shots of the Barrow gang, highlighting the increasing chaos and fractures within their dynamic as the story progresses.

Lighting Style of “Bonnie and Clyde”

Guffey’s lighting in “Bonnie and Clyde” is a masterclass in mood setting, striking a balance between realism and stylization. He predominantly used naturalistic lighting to enhance the authenticity of the Depression-era setting, lending the film an authentic and timeless quality. Daylight scenes are often bright and washed-out, bathed in warm, golden hues that evoke the heat and desolation of the rural American landscape. This symbolizes the fleeting freedom of the Barrow gang’s escapades.

In contrast, interior scenes often feature stark lighting with high contrast, highlighting the tension and volatility of the characters’ lives. A particularly notable lighting choice is in the scene where Bonnie visits her mother. Shot through a hazy, dreamlike filter, the lighting gives the moment a prophetic quality, foreshadowing the tragic end of Bonnie and Clyde’s journey. This deliberate manipulation of light and shadow enhances the emotional weight of the narrative.

Lensing and Blocking in “Bonnie and Clyde”

The choice of lenses and the blocking of actors were critical in achieving the film’s distinctive look. Guffey frequently opted for wide-angle lenses, which allowed for greater depth of field and kept both the foreground and background in sharp focus. This technique helps to establish the environment as a character in itself, giving the film a sense of scale and grandeur.

Blocking—the arrangement of actors within the frame—was equally thoughtful. Director Arthur Penn and Guffey worked meticulously to ensure that the characters’ positions within the frame reflected their dynamics. Actors move fluidly within the space, and their positioning often reflects their relationships and power dynamics. For instance, Bonnie and Clyde are often positioned at the center of the frame, reinforcing their status as the emotional core of the story. In contrast, other characters, such as Buck and Blanche, are frequently placed at the periphery, highlighting their secondary roles in the narrative.

Color in “Bonnie and Clyde”

Although “Bonnie and Clyde” was shot in color, its palette is deliberately muted, evoking the sepia tones of old photographs. The color palette is subdued yet impactful, reinforcing the film’s historical setting while also lending it a timeless quality. Earth tones dominate the scenery browns, yellows, and greens reflecting the rural, Depression-era environment and grounding the film in its context.

The costumes of Bonnie and Clyde play a significant role in the film’s color story. Bonnie’s vibrant outfits, often in shades of red, stand out against the muted backgrounds, symbolizing her fiery spirit and passion. Clyde’s more subdued wardrobe reflects his internal conflict and stoic demeanor. This selective use of color intensifies key moments and draws the viewer’s attention to important narrative elements, enhancing the emotional depth of the characters and their story.

Technical Aspects of “Bonnie and Clyde”

Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS & PRODUCTION CREDITS| Genre | Crime, Drama, Heist, Road Trip, Outlaw, Western, Gangster, Thriller, True Crime |

| Director | Arthur Penn |

| Cinematographer | Burnett Guffey, A.S.C. |

| Production Designer | Dean Tavoularis |

| Costume Designer | Theadora Van Runkle |

| Editor | Dede Allen |

| Time Period | 1930s |

| Color | Cool, Desaturated |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light, Low contrast, Edge light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Sunny |

| Story Location | United States of America > Texas |

| Filming Location | United States of America > Texas |

| Camera | Mitchell BNCR |

On a technical level, “Bonnie and Clyde” broke new ground in Hollywood filmmaking. The use of squibs small explosive devices used to simulate gunshot wounds was revolutionary at the time. This innovation allowed for the film’s graphic depiction of violence, which was unprecedented in American cinema. The climactic ambush scene, where Bonnie and Clyde are riddled with bullets, remains one of the most visceral and impactful sequences in film history.

From a cinematography standpoint, the film was shot using Panavision cameras and lenses, which were cutting-edge technology at the time. The use of these cameras allowed for greater flexibility in shot composition and depth of field control. The film stock chosen contributed to the grainy texture of the images, enhancing the gritty realism that Guffey aimed to achieve. As a colorist, I appreciate how these technical choices interplay with the film’s thematic content, creating a cohesive and immersive visual experience.

Editing also played a crucial role in the film’s success. Dede Allen’s groundbreaking work introduced a new style of rapid cuts and overlapping action, drawing inspiration from the French New Wave. This editing style created a sense of immediacy and energy, keeping audiences engaged while also heightening the emotional impact of key scenes.

Conclusion

“Bonnie and Clyde” remains a seminal work in cinematic history, largely due to Burnett Guffey’s innovative cinematography. His ability to integrate inspiration from the French New Wave, employ dynamic camera movements, and make deliberate choices in composition, lighting, lensing, and color all contribute to the film’s enduring impact. Analyzing these elements has deepened my appreciation for the art of cinematography and its power to shape storytelling.

As a filmmaker and colorist, I find “Bonnie and Clyde” to be a fascinating study in how visuals can elevate a story. Its influence on modern cinema cannot be overstated, paving the way for a new era of bold, boundary-pushing filmmaking. For anyone passionate about the art of cinema, “Bonnie and Clyde” is an essential watch and a timeless source of inspiration.

- Also Read: CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS OF CALL ME BY YOUR NAME (IN DEPTH)

- Also Read: CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS OF BLACK SWAN (IN DEPTH)

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →