My name is Salik Waquas, and I am a filmmaker and colorist deeply passionate about the visual arts. As the owner of a post-production color grading suite, I’ve spent years exploring how cinematography can elevate storytelling to profound heights. One film that has significantly influenced my understanding of visual storytelling is Edward Yang’s 1991 masterpiece, “A Brighter Summer Day.” Its intricate narrative and compelling cinematography offer a rich tapestry of techniques that continue to inspire me.

About the Cinematographer

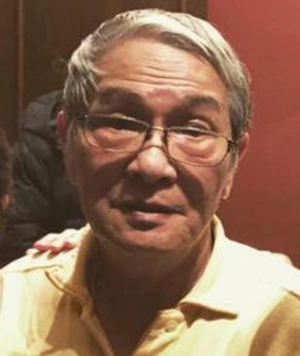

The visual narrative of A Brighter Summer Day was masterfully crafted by cinematographer Hui Kung Chang. His collaboration with Edward Yang resulted in a visual language that is both authentic and evocative, capturing the socio-political complexities of 1960s Taiwan. Chang’s work is nothing short of revolutionary; he balances technical precision with raw, naturalistic beauty, immersing us in a world filled with moral ambiguity, youthful angst, and political upheaval.

Chang’s cinematography feels like a character in itself—detached yet intimate, deliberate yet fluid. The frames he and Yang created don’t merely document the story; they evoke emotions and layer storytelling into every shot. The film’s visuals transport us back to 1960s Taipei with an authenticity that resonates universally.

Inspiration for the Cinematography of “A Brighter Summer Day”

The cinematography draws inspiration from a deep well of influences, including Italian neorealism and classical Chinese art. The muted realism reflects the restrained emotional tenor of the characters, a deliberate choice by Yang and Chang to favor authenticity over melodrama. The socio-political backdrop of 1960s Taiwan—marked by tension between native Taiwanese and mainland Chinese immigrants—is mirrored in the framing, lighting, and compositions.

Edward Yang was also influenced by American cinema and Western culture, elements that play a crucial role in the story. The infusion of American rock and roll, Elvis Presley references, and youth gang culture highlights a growing generational divide. This blend of Eastern and Western influences is visually evident in the depiction of spaces—traditional Taiwanese homes juxtaposed against Westernized youth hangouts—each space reflecting the fractured identity of the characters.

Camera Movements Used in “A Brighter Summer Day”

One of the defining features of the film’s cinematography is its restrained and contemplative camera movement. The film largely relies on static shots, with occasional pans and tilts that feel deliberate rather than kinetic. This approach creates a sense of detachment, forcing the audience to absorb the environment and characters without distraction.

For instance, the camera often remains stationary during pivotal scenes, allowing the actors’ performances and the mise-en-scène to convey the emotional depth of the narrative. The static compositions make us feel like silent observers, emphasizing the voyeuristic quality of the story.

However, the film strategically employs dynamic camera movements during moments of heightened emotion or tension. Tracking shots during gang confrontations carry significant weight precisely because they contrast with the film’s otherwise stationary aesthetic. These choices emphasize the chaos erupting within an otherwise orderly, repressed society.

Compositions in “A Brighter Summer Day”

The compositions are meticulously crafted to reflect the characters’ internal states and the film’s thematic concerns. Characters are often dwarfed by their surroundings, reinforcing themes of insignificance in a politically oppressive and culturally fragmented environment. Wide shots dominate the film, with characters frequently placed amidst expansive environments, emphasizing their isolation or integration within the community.

Negative space is utilized effectively to convey a sense of emptiness or tension. The framing often positions characters within vast spaces, highlighting their loneliness even when surrounded by others. This visual metaphor extends to the depiction of strained relationships; characters are physically close but emotionally distant, their relationships reflected in the spatial dynamics within the frame.

A striking motif is the use of framing devices like windows or doorways, which serve to separate characters physically and emotionally. This technique creates a sense of voyeurism, as if we are peering into their world—simultaneously fostering intimacy and detachment.

Lighting Style of “A Brighter Summer Day”

The lighting in the film is predominantly naturalistic, utilizing available light sources to create an authentic atmosphere. This subdued and naturalistic approach enhances the realism of the scenes and allows for subtle variations in mood. Soft, diffused light dominates interior scenes, casting gentle shadows that contribute to the film’s intimate and contemplative tone.

Practical lighting is employed to great effect, especially in scenes set in classrooms, homes, and street corners. The lighting often stems from natural sources within the frame, such as lamps or windows, grounding the film in reality and making its emotional beats more impactful.

Night scenes are particularly compelling. The use of streetlamps and window light creates pockets of intimacy amid the darkness, contrasting with the harsh fluorescent lights in public spaces that strip the characters of privacy and individuality. This contrast underscores the film’s exploration of identity and internal conflicts.

Lensing and Blocking of “A Brighter Summer Day”

The choice of lenses and the blocking of scenes are integral to the film’s visual storytelling. While specific technical details about the lenses used are scarce, the visuals suggest a preference for mid-range focal lengths (35-50mm). This creates a naturalistic perspective that mirrors human vision, allowing the audience to feel like silent observers within the unfolding drama.

The use of wide-angle lenses captures expansive environments, situating characters within their surroundings and emphasizing their place within the broader socio-political context. Close-ups are sparingly used, making them more impactful when they occur, often during moments of intense emotional significance.

Blocking plays a pivotal role in conveying relationships and emotional states. Characters are deliberately positioned within the frame to reflect their dynamics. In gang scenes, for instance, characters are grouped together, but the spacing between them suggests emotional distance. Conversely, family scenes often feature characters in close proximity yet emotionally disconnected, their strained relationships mirrored in their physical arrangements.

Color of “A Brighter Summer Day”

The film’s color palette is understated yet deliberate. Muted, earthy tones dominate, reflecting the somber mood of the narrative and the repressive socio-political environment of 1960s Taiwan. This subdued palette mirrors the muted emotional landscape of the characters, enhancing the film’s naturalistic aesthetic.

Occasionally, bursts of color break through the subdued tones, such as the bright uniforms of schoolchildren or the neon lights of a movie set. These moments of vibrancy often carry thematic weight, symbolizing fleeting hope or the intrusion of external cultural influences.

One of the most poignant uses of color is in the depiction of Xiao Si’s gang life. The dimly lit alleys and shadowy interiors where the gangs congregate contrast starkly with the brighter, more open spaces of his home and school. This visual dichotomy underscores his internal conflict and fractured identity.

Technical Aspects: Camera Used, Lenses, etc.

While specific details about the cameras and lenses used in the production are not extensively documented, it’s evident that the filmmakers employed equipment that allowed for flexibility in capturing both wide landscapes and intimate interiors. The choice of equipment facilitated the film’s naturalistic aesthetic, enabling the cinematographer to work effectively within the varied lighting conditions present in the film’s diverse locations.

The film’s use of long takes and deep focus reflects Edward Yang’s commitment to realism. By avoiding quick cuts and allowing scenes to unfold organically, Yang and Chang create a sense of immersion that draws the viewer into the world of the film. The deep focus allows multiple elements within the frame to remain sharp, encouraging the audience to explore the visual details and layers of meaning within each scene.

- Also Read: CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS OF PATHS OF GLORY

- Also Read: CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS OF SOME LIKE IT HOT