Diving back into Castle in the Sky (1986) isn’t just a trip down memory lane it’s an encounter with a foundational piece of world-building. This is an epic, steampunk dreamscape that blends magic and industry so seamlessly you can truly lose yourself in it. And as a colorist, I always do.

About the Cinematographer (and the Ghibli Method)

In animation, especially in the pre-digital era of the 80s, the role of a “cinematographer” functions differently than on a live-action set. Here, Hirokata Takahashi is the credited cinematographer, but in the Ghibli ecosystem, that role is an intimate collaboration. You have the legendary Michiyo Yasuda the “Godmother” of Ghibli’s color department shaping the palette, while Hayao Miyazaki acts as the ultimate visual auteur, meticulously storyboarding the “lens” and “lighting” of every frame.

The execution of this vision falls to a collective of geniuses. You have Nizō Yamamoto on art direction and Yoshinori Kanada heading up animation. They are, for all intents and purposes, the lighting technicians and camera operators of this world. They decide how a sunset bleeds across a character’s face or how atmospheric haze settles over a valley. My goal is to peel back these layers and analyze their choices as if they were made by a singular, guiding hand.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

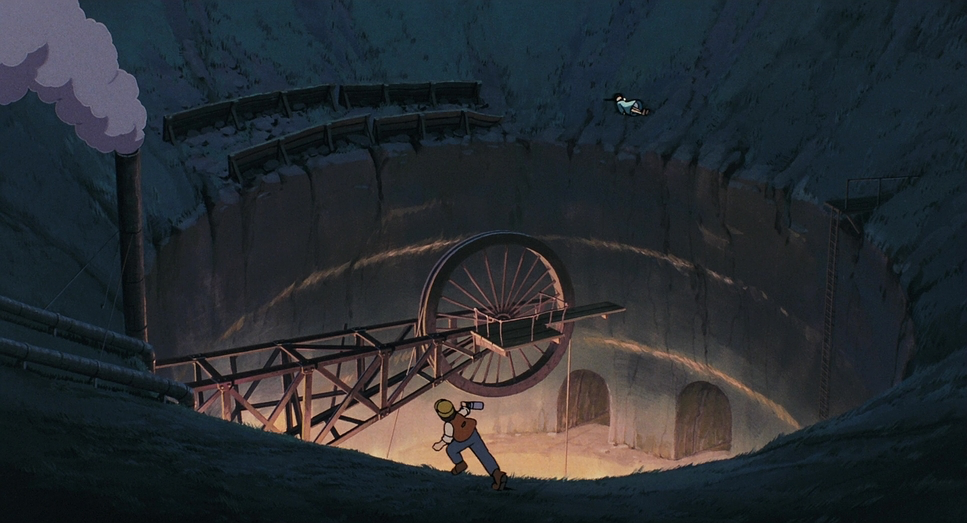

The visual landscape of Castle in the Sky is grounded in a way most fantasy isn’t. It’s well-documented that the Ghibli team scouted rural Wales, and you can feel that grit in the 19th-century mining aesthetic of Patsu’s home. It’s not just a “pretty” background; it’s a commitment to authenticity.

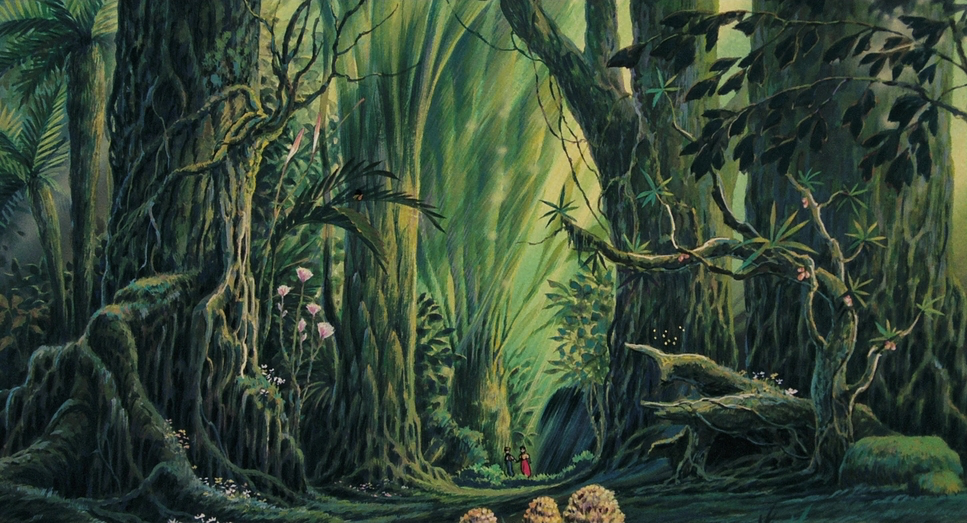

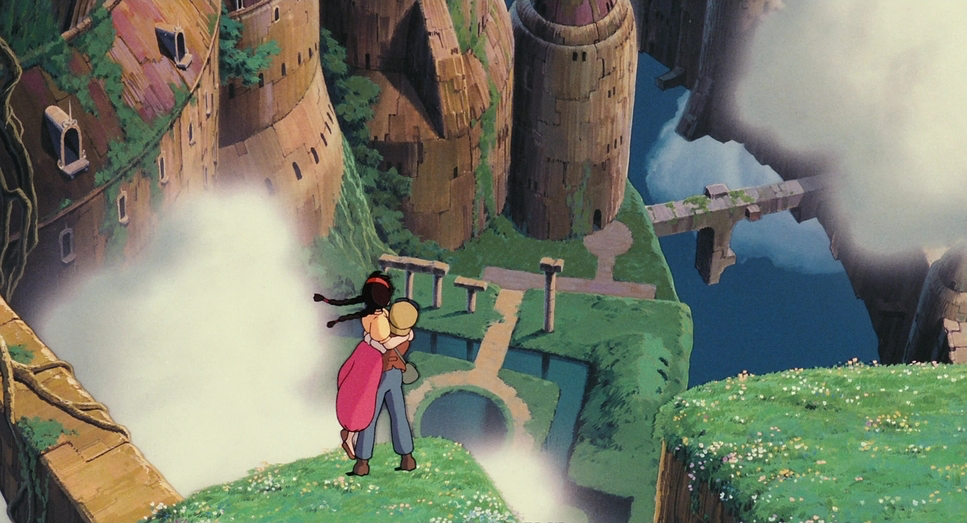

Because the world feels lived-in with its rusted factories, derelict machinery, and soot-stained trains the “cinematography” feels believable. When the sun hits those industrial structures or filters into the subterranean tunnels, it doesn’t feel like a cartoon. It feels like a memory. This grounding makes the eventual reveal of the floating city, Laputa, even more breathtaking. By anchoring the film in the mundane beauty of industrial Wales, Miyazaki earns the right to take us to the clouds.

Camera Movements

In 1986, “camera movement” meant the painstaking use of multiplane cameras and parallax scrolling. Castle in the Skyis a high-octane film, and the visual language reflects that relentless energy. It’s breathless.

We see soaring aerial shots that establish the sheer scale of the airships the kind of wide, sweeping “crane” shots that give you a physical sense of vertigo. When things get intense, like the chase sequences with the pirates, the “camera” becomes agile. It whips and pans, mimicking the frantic energy of a handheld camera but with a precision that only animation can achieve.

Take the moment Sheeta first drifts down from the sky. The vertical “tracking” shot follows her descent with a dream-like grace, slowly revealing Patsu below. It’s a perfect use of movement to introduce magic. If I have one minor professional critique, it’s that the film is so fast-paced it rarely stops to breathe. A few more lingering “push-ins” on the characters’ faces during the quiet moments might have deepened the emotional stakes, but the kinetic energy is clearly the priority here.

Compositional Choices

Miyazaki’s eye for composition is legendary. He loves a wide shot, using the vast, “Ghibli Blue” sky as negative space to emphasize how small and isolated our heroes are against the world’s grand machinery.

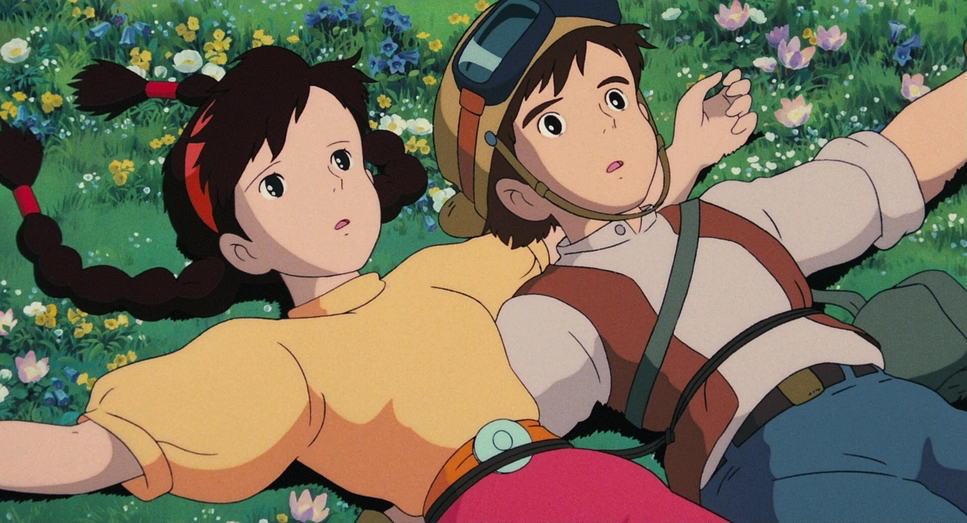

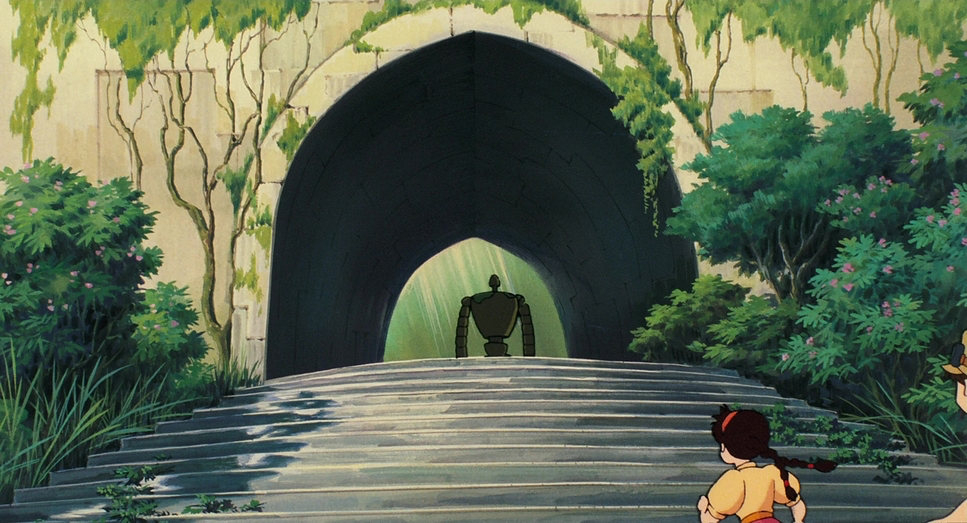

But look closer at the “blocking” within those frames. When Patsu and Sheeta are together, they often share a tight, balanced frame that visually cements their bond. When the villains appear, the angles shift. We see Dutch angles (tilted frames) or extreme low angles to make the fortresses and robots feel dominating and oppressive. Even in a static shot of the mining town, the overlapping rooftops and steep streets create leading lines that guide your eye exactly where Miyazaki wants it to go. It’s complex, but perfectly readable.

Lighting Style

The lighting here is a masterclass in “motivated” illumination. It’s never just flat. At night, the warm, orange glow from a window or a lantern acts as a practical light source against the cool, deep purples of the sky. This “warm-vs-cool” contrast is a staple of Ghibli’s look, and it adds incredible depth.

In daytime, the sun is a hard, directional source. You can see it in the way light glints off the metallic hulls of the airships or catches the facets of Sheeta’s crystal. As a colorist, I’m inspired by how they used light to define texture making the “rustic” robots feel aged and metallic through nothing but paint and shadow. It’s about the psychology of light: using low-key, mysterious lighting for the villain Muska, while Patsu and Sheeta are almost always bathed in a hopeful, high-key glow.

Lensing and Blocking

Even without a physical glass lens, the team “simulates” focal lengths. They use wide “lenses” (around 24mm or 35mm equivalents) for those grand landscapes, giving us an expansive view of the world. Then, they’ll use a “telephoto” effect to compress space, making a pursuing airship look massive and terrifying as it looms behind our heroes.

The blocking is equally choreographed. Characters move with purpose. The way Patsu and Sheeta move in sync—often protecting each other tells you everything you need to know about their relationship without a single line of dialogue. It’s active, fluid, and keeps the story moving even during exposition-heavy scenes.

Color Grading Approach

This is my wheelhouse. Analyzing the “grade” of a 1986 film means looking at the original painted cels and the legendary work of Michiyo Yasuda. The palette is full of life, but it’s sophisticated.

I see a very deliberate use of color harmony. The iconic deep blues of the sky are balanced by the warm oranges of fire and machinery. For a colorist, that’s “color contrast 101,” but Ghibli does it with a painterly touch. The greens in this film are particularly important a vibrant, emerald green that represents nature reclaiming the ruins of Laputa.

If I were remastering this for a modern 4K release, my priority would be preserving that filmic “roll-off.” I’d want to keep the highlights soft and luminous rather than “digital-harsh.” You want to maintain that slight desaturation in the shadows while letting the magical glows pop. It’s a delicate balance that keeps the world feeling immersive and romantic rather than cartoonish.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Castle in the Sky (1986) – Technical Specifications

| Genre | Action, Adventure, Animation, Family, Fantasy, Romance, Traditional Animation, Anime |

| Director | Hayao Miyazaki |

| Cinematographer | Hirokata Takahashi |

| Production Designer | Hayao Miyazaki |

| Editor | Hayao Miyazaki, Takeshi Seyama, Yoshihiro Kasahara |

| Colorist | Michiyo Yasuda |

| Time Period | 1970s |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.85 |

| Format | Animation |

| Lighting | Hard light, High contrast, Top light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Story Location | Laputa |

| Film Stock / Resolution | 4K |

This was the era of traditional cel animation no CG shortcuts. Every frame was a hand-painted piece of art, photographed layer by layer. The depth we see in the aerial battles was achieved through the sheer brute force of talent and multiplane camera work.

There’s a softness to hand-drawn animation that digital tools still struggle to replicate. Whether it’s the way the fire is rendered or the “weight” of the robots as they move, you can feel the human hand in every frame. The magic crystal is a great example: making a painted object look like it’s emitting light requires incredible layering and an expert understanding of color theory. It’s a reminder that groundbreaking visuals come from craft, not just hardware.

- Also read: COOL HAND LUKE (1967) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: CINDERELLA MAN (2005) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →