Whenever I revisit Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) ,I’m struck by how it defies the “aging” process. Released in 1969, it sits right on the cusp of the New Hollywood era a film that respects the Western genre while actively deconstructing it. For a filmmaker, the visual language here is a goldmine. It’s not just about pretty landscapes; it’s about how every technical choice from the anamorphic lensing to the film stock serves the narrative of two outlaws watching their world disappear. Let’s break down the visual grammar of this masterpiece.

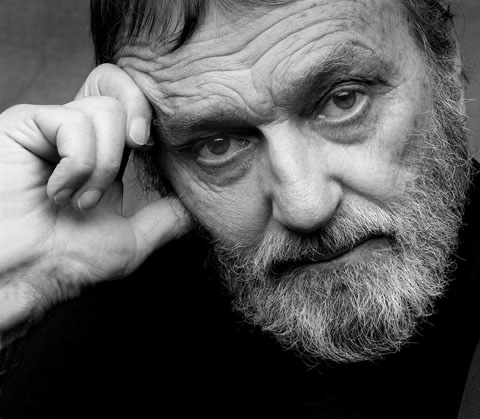

About the Cinematographer

The look of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid belongs to the late, great Conrad L. Hall, ASC. If you work in this industry, Hall is a titan. He wasn’t interested in the “perfect” Hollywood lighting of the 50s; he wanted accidents, flares, and organic texture. He famously noted that he liked to “make mistakes” on purpose to find emotional truth.

In Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Hall’s work is characterized by a willingness to overexpose windows and let shadows fall where they may. He moved away from the heavy, theatrical lighting of the classic studio Westerns and embraced a more naturalistic, gritty reality. As a colorist, when I look at Hall’s work, I see a “thick” negative rich with information, unafraid of darkness, and prioritizing mood over simple visibility.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Visually, the film functions as a eulogy. The story takes place in the late 1890s, an era when the Wild West was being fenced in and civilized. Hall and director George Roy Hill needed a visual style that felt nostalgic without being cheesy.

This is most obvious in the opening sequence. The decision to start with a sepia-toned newsreel look isn’t just a gimmick; it grounds the characters in history before we even see their faces. It tells us, “These men are already ghosts.” When the film finally bleeds into color, it doesn’t jump to hyper-saturated Technicolor. It transitions into a muted, dusty palette that maintains that feeling of a fading memory. It’s a brilliant way to align the audience with the protagonists’ inevitable obsolescence.

Camera Movements

Despite the high-stakes chases, the camera movement here is surprisingly disciplined. We don’t see the shaky, handheld chaos common in modern action films. Instead, Hall uses the smooth, heavy movement of the Panavision Panastarcamera to create a sense of inevitability.

The tracking shots are particularly effective. In the chase sequences across the rocky desert, the camera often tracks laterally, keeping pace with the horses. This creates a “parallax effect” where the foreground rushes by while the distant mountains barely move, emphasizing the vast distances the characters have to cover. The movement is observational, almost detached, which makes the bursts of action like the train explosion or the cliff jump feel significantly more impactful because the camera isn’t trying to manufacture energy; it’s simply capturing the stunt.

Compositional Choices

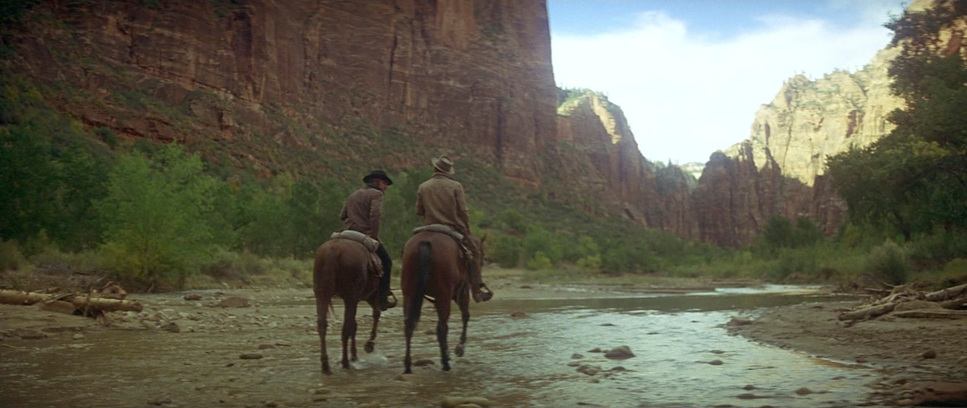

Shooting on a 2.35:1 anamorphic aspect ratio allowed Hall to utilize negative space masterfully. One of the most effective compositional tools in the film is “deep staging.” There are several shots where Newman and Redford are placed in the extreme foreground, while the “super-posse” trailing them is visible as tiny specks miles away in the background.

This isn’t just a “pretty shot” it’s narrative efficiency. It establishes the geography of the chase and the relentless nature of their pursuers in a single frame. The wide aspect ratio also isolates the characters. By framing them small against massive rock formations in Zion National Park, Hall visually reinforces their helplessness against the changing world. They are small men in a massive, indifferent landscape.

Lighting Style

The lighting strategy relies heavily on available daylight, modified to look soft and natural. Because the film is set largely outdoors, Hall used the harsh sun to his advantage. However, rather than filling in every shadow with massive reflectors, he often let the contrast ratio stay high.

For the interiors, the lighting is motivated and moody. In the darker saloon or hideout scenes, you can see Hall using “practicals” (lamps and lanterns) to justify the light sources. The roll-off on the highlights is incredibly smooth a characteristic of the celluloid of that era. He wasn’t afraid of silhouette, either. There are moments where faces are underexposed to read the bright exterior background, prioritizing the environment over the actor’s face, which adds to the documentary-style realism they were aiming for.

Lensing and Blocking

Hall relied on the Panavision C Series anamorphic lenses for this film. These lenses are legendary for a reason they have unique optical imperfections, subtle barrel distortion, and beautiful flares that modern glass tries (and often fails) to replicate.

You can see the anamorphic influence in the way the background blurs; the bokeh has that distinct oval shape. Hall uses this shallow depth of field during intimate dialogue scenes to separate the actors from the background. In terms of blocking, notice how often Butch and Sundance are framed together. They are rarely isolated in single shots during the first half of the film. They are a unit. As the pressure mounts in Bolivia, the blocking starts to separate them more, or pin them against walls, visually boxing them in as their options run out.

Color Grading Approach

As a colorist, this is where I really geek out. While the original 1969 release was timed photochemically at the lab, the version most of us watch today was likely restored and graded by colorist Mark Nakamine. The goal of the restoration seems to be preserving the integrity of that original print look.

The palette is strictly “subtractive.” We don’t see rich, electric blues or neon greens. The greens of the foliage are pushed toward yellow/brown, and the skies are often a pale cyan rather than a deep royal blue. This creates an “analog warmth” a dusty, golden-hour feel that permeates the entire runtime. It unifies the locations, making the U.S. and Bolivia feel like part of the same dusty purgatory. The skin tones are kept natural but warm, sitting comfortably in that lower-midrange of the waveform, avoiding the “digital plastic” look of modern sensors.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – Technical Specs

| Genre | Action, Adventure, Comedy, Crime, Drama, History, Outlaw, Small town, Thriller, Western, Epic |

| Director | George Roy Hill |

| Cinematographer | Conrad L. Hall |

| Production Designer | Phillip M. Jefferies, Jack Martin Smith |

| Costume Designer | Edith Head |

| Editor | John C. Howard, Richard C. Meyer |

| Colorist | Mark Nakamine |

| Time Period | 1800s |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.35 – Anamorphic |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Sunny |

| Story Location | United States of America > Wyoming |

| Filming Location | Utah > Zion National Park |

| Camera | Panavision Panastar |

| Lens | Panavision C series |

| Film Stock / Resolution | 5254/7254 100T |

The technical constraints of 1969 dictated much of the look. The film was shot on Kodak 5254, a 100T (Tungsten) stock. By modern standards, 100 ASA is incredibly slow. This meant Hall needed a lot of light.

To get a proper exposure on a 100 ASA stock, especially for interiors or during the “magic hour,” he had to be precise. The grain structure of the 5254 is prominent but organic. It provides a texture that digital noise reduction often strips away. The fact that they captured clean, sharp anamorphic images on such slow stock in rugged locations like Mexico (doubling for Bolivia) and Utah is a testament to the crew’s technical discipline. There was no “fixing it in post” what they caught on that negative is exactly what we see.

- Also read: IP MAN (2008) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: ROSEMARY’S BABY (1968) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →