Watching Ben-Hur forces me to shift gears completely. It requires a different mindset, one that appreciates a time when the “look” wasn’t something you dialed in later—it was baked into the negative on the day, under the blazing sun. When I watch this film, I’m not just seeing a story; I’m looking at a massive, industrial-scale feat of engineering. It’s the kind of cinema that makes me lean forward, trying to figure out how they managed to expose 65mm film so consistently in conditions that would make modern crews crumble.

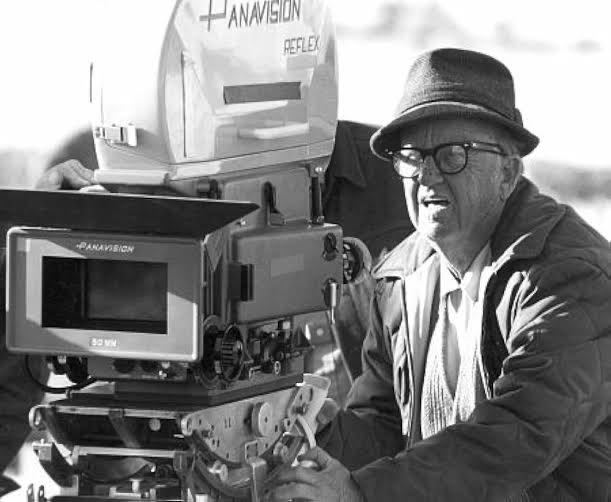

About the Cinematographer

Robert Surtees, ASC, wasn’t just a “cinematographer” on this production; he was effectively a general commanding a visual army. By 1959, he had already proved himself with King Solomon’s Mines and Oklahoma!, but Ben-Hur was a different beast. Shooting on 65mm isn’t like grabbing an ARRI Alexa; the depth of field is razor-thin, and the equipment is cumbersome.

Surtees had to balance the sheer logistics of the format with the narrative need for intimacy. He understood that if the audience didn’t care about Judah Ben-Hur, the 18-acre sets wouldn’t matter. What impresses me is his patience. You can feel the discipline in his lighting and framing—he wasn’t just capturing coverage; he was executing a very specific, rigid plan that served Wyler’s direction without letting the technology overshadow the human drama.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Context is everything here. In the late 50s, Hollywood was terrified of television. TV was free, small, and black-and-white. To survive, cinema had to be the opposite: expensive, massive, and bursting with color. Ben-Hur was MGM’s “all-in” bet to prove that the theater experience was irreplaceable.

The visual strategy was reactionary in the best way possible. They didn’t just want to show you a wide shot; they wanted to assault your peripheral vision. The inspiration wasn’t just biblical paintings; it was the concept of “spectacle” as a physical sensation. They needed the audience to feel the heat of the desert and the vibration of the chariots. It was a survival tactic for the studio, pushing them to create a visual language that was impossibly grand simply because it had to be.

Camera Movements

When you are shooting with the MGM Camera 65 system (which used huge blimps to silence the noise), you don’t exactly whip the camera around. Every movement in Ben-Hur feels deliberate because it had to be. The camera has weight.

The tracking shots in this film, particularly during the chariot race, are a masterclass in kinetic energy. They mounted these massive cameras on cars and dollies that had to match the speed of galloping horses. Unlike modern action movies where “shaky cam” hides the cuts, the movement here is smooth and sustained. It puts you right in the dust. I noticed the camera often sits surprisingly low, mirroring the eyeline of the racers. It creates a terrifying sense of speed that feels dangerous because, frankly, it was.

Compositional Choices

Surtees was working with the Ultra Panavision 70 aspect ratio—a staggering 2.76:1. That is an incredibly wide canvas to fill. A lesser DP would have left a lot of dead space, but Surtees treated the frame like a Renaissance fresco.

He used deep focus to layer the storytelling. In the wide shots of the Roman legions, you aren’t just looking at the soldiers; your eye can travel all the way to the background architecture and the mountains beyond. It’s a diorama effect that gives the world scale. Even in the dialogue scenes, he utilizes the extreme width to isolate characters. He often pushes Heston to the far edge of the frame, using the negative space to emphasize his isolation or the overwhelming power of the Roman Empire bearing down on him. It’s not just “rule of thirds”; it’s a deliberate use of screen real estate to convey power dynamics.

Lighting Style

The lighting here is what I’d call “unapologetically source-y.” Surtees didn’t try to soften the harsh reality of the story with excessive diffusion. In the desert sequences, he treats the sun as a hostile character. It’s hard, directional light that casts deep, sharp shadows.

From a colorist’s perspective, the contrast ratio is fascinating. In the galley scenes, he leans into heavy chiaroscuro—pools of torchlight surrounded by crushed blacks. It’s moody and theatrical, almost like a stage play, but it sells the claustrophobia. He wasn’t afraid to let faces fall into shadow. Today, we obsess over “lifting the shadows” to see every detail, but Surtees knew that letting the blacks crush slightly added to the emotional weight and the texture of the film.

Lensing and Blocking

Shooting 65mm means you get incredible resolution, but your lenses behave differently. You need a lot of light to stop down enough to keep things in focus. The clarity in Ben-Hur comes from that massive negative area—it’s just physically more information than 35mm.

The blocking had to be surgically precise. With a 2.76:1 frame, you can’t just have two actors standing in the middle; it looks empty. Wyler and Surtees arranged groups of actors in diagonals and clusters to lead the eye across the screen. In the chariot race, the spatial geography is perfect—you always know where Ben-Hur is relative to Messala. That’s not an accident; that’s careful blocking tailored specifically for wide-angle anamorphic lenses that distort space slightly, making the distances feel even more dramatic.

Color Grading Approach

If I were to get the original scans of Ben-Hur in my grading suite today, my first instinct would be: “Don’t ruin it.” The color palette of the late 50s was chemically defined by the film stock and the developing baths (likely Technicolor dye-transfer prints for the release).

The film has that distinct, rich Eastmancolor look—bold, authoritative reds for the Romans, earthy ochres for the Judean landscapes, and healthy, bronze skin tones that pop. If I were grading this now, I wouldn’t try to “modernize” it with a teal-and-orange LUT. My focus would be on contrast shaping. I’d want to preserve that beautiful, creamy highlight roll-off that old film stocks had—where the bright sky blooms slightly rather than clipping into digital white.

I would focus on hue separation to ensure the costumes stand out against the set design, but I’d keep the print-film sensibilities intact. That means leaving the grain structure alone and allowing the colors to feel dense and saturated, rather than clinical. The goal would be to replicate the feeling of projected film, not a pristine digital file.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Ben-Hur (1959)

Technical Specifications| Genre | Action, Adventure, Drama, Epic, History, Military, Ancient Wars, War, Costume Drama, Costume |

| Director | William Wyler |

| Cinematographer | Robert Surtees |

| Production Designer | Vittorio Valentini |

| Costume Designer | Elizabeth Haffenden |

| Editor | John D. Dunning, Ralph E. Winters |

| Time Period | Ancient: 2000BC-500AD |

| Color | Warm |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.76+ – Anamorphic |

| Format | Film – 65mm / 70mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, Top light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Sunny |

| Story Location | … Europe > Roman Empire |

| Filming Location | … Culver City > Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios – 10202 W. Washington Blvd |

| Camera | Mitchell, Super Panavision 70 |

We throw the word “epic” around a lot, but Ben-Hur was industrial filmmaking. The budget was $15 million—astronomical for the time. The 18-acre chariot arena wasn’t a digital extension; it was real rock, dirt, and timber carved out of the earth at Cinecittà Studios.

As a filmmaker, thinking about the logistics gives me a headache. Lighting an 18-acre exterior set for consistency over weeks of shooting requires an army of grips and gaffers managing huge arc lights and overhead silks. They didn’t have lightweight LEDs or wireless monitoring. Everything was heavy, hot, and slow. The fact that they achieved such a polished look with that cumbersome gear is a testament to the manual labor and technical discipline of the crew.

- Also Read: THE SOUND OF MUSIC (1965) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also Read: BEFORE SUNSET (2004) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →