In the world of filmmaking, there are movies that tell you what to think, and then there are movies that just let you look. Ron Fricke’s Baraka (1992) is firmly the latter. It doesn’t have a protagonist, dialogue, or a traditional three-act structure. Instead, it offers a purely visual transmission a non-verbal meditation that lives up to its name (meaning “blessing” or “essence” in Arabic).

Watching it isn’t like consuming a narrative; it feels more like a recalibration of your senses. For me, spending my days staring at scopes and tweaking curves at Color Culture, Baraka is the ultimate reference point. It grabs your attention not with plot twists, but with the sheer weight of its imagery. It captures the world in a way that feels both ancient and immediate, forcing you to confront the “existential” reality of our planet without a single spoken word. It’s a masterclass in visual grammar that every filmmaker needs to study.

About the Cinematographer

You can’t talk about Baraka without understanding Ron Fricke’s specific methodology. Before this, he shot Koyaanisqatsi, which effectively invented this style of non-verbal, time-manipulated cinema. But on Baraka, Fricke wasn’t just the Director of Photography; he was the director and the camera operator. That singular control is rare, and you can feel it in the footage.

The production logic was insane by modern standards: a lean crew of just five people traveling to 24 countries over 14 months. When you look at the logistics of hauling 65mm cameras up mountains and into temples with such a small team, you realize the level of commitment involved. Fricke’s philosophy was to construct a story through the “score composition” and the images themselves, rather than a script. He wasn’t chasing a shot list; he was chasing moments, allowing the atmosphere of a location to dictate the frame.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

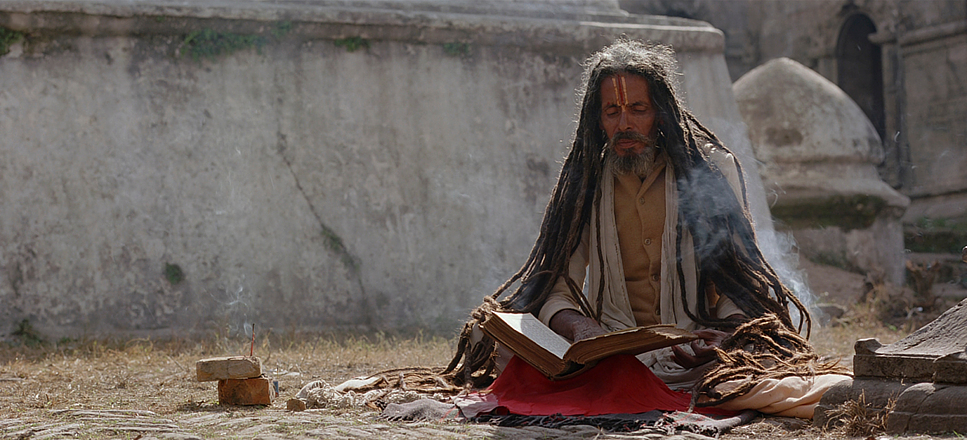

The cinematography feels rooted in a desire to strip away the filmmaker’s ego and simply observe. It’s the ultimate “fly on the wall” documentary, but the wall is the entire planet. The film oscillates between the raw serenity of nature and the chaotic rhythm of human society religious rites, industrial complexes, and tribal ceremonies without explicitly judging either.

The opening sequence is the perfect example of this observational power. We start with snowy mountains and Japanese macaques bathing in hot springs. Fricke holds on a static shot of a monkey just sitting there, eyes closed, taking the world in. It’s not just a cutaway; it’s an establishing shot for life on Earth. It forces a sense of “oneness” between the viewer and the subject. Later, when we see the collective chant (the Kecak dance in Indonesia), the camera doesn’t frantically cut around. It holds the frame, letting the “stunning footage” of the collective human experience wash over you. The pacing draws a deliberate line from tranquil landscapes to the intensity of city life, mirroring the ebb and flow of civilization itself.

Camera Movements

In Baraka, camera movement is used to manipulate time rather than space. Fricke is the godfather of the modern motion-control time-lapse. He custom-built camera rigs that allowed him to move the camera imperceptibly slowly while capturing frames over long periods. This transforms mundane events traffic flows, cloud formations, people walking into hypnotic patterns that look organic, almost like blood moving through veins.

When the camera isn’t doing these complex time-lapses, it is often locked off completely. The stillness is aggressive; it forces you to scan the frame. When he does move the camera in real-time, it’s usually a slow, creeping dolly or crane move that adds an omniscient, god-like perspective. This specific pacing breathes room into the edit. It doesn’t rush you. Some viewers describe the effect as a kind of “ego death” or a psychedelic experience, simply because the camera removes the usual human perception of time, dissolving the boundary between the observer and the observed.

Compositional Choices

Fricke’s composition relies heavily on the 65mm aspect ratio (2.20:1). He paints on a massive canvas, balancing wide, epic scales with intimate details. He uses negative space brilliantly letting a massive desert landscape or a sprawling cityscape dominate the frame so the eye has to wander to find the subject.

What stands out to me is how he frames humans within their environment. He rarely isolates a face with a shallow depth-of-field telephoto lens to blur out the background. Instead, he stops down, keeping the environment sharp, showing how culture and geography are inseparable. The film also uses visual juxtaposition as a montage technique. The famous sequence matching factory-line chickens to commuters on a subway escalator is a punch in the gut. By framing them identically, he creates a thematic link about industrial conformity without saying a word. By refusing to use lower-thirds or titles to label locations, he forces that “oneness” again you stop thinking “this is Tokyo” or “this is New York” and start seeing it simply as “Humanity.”

Lighting Style

Lighting Baraka wasn’t about setting up 18Ks and diffusions; it was about patience. The lighting is predominantly natural, but “natural” implies it was easy. In reality, Fricke and his team were masters of waiting for the right conditions. They treated light as a character.

You can see the “golden hour” texture bathing the ancient temples, but you also see the harsh, unforgiving top-light of the midday sun in the desert sequences. They used the hard shadows to create volume and texture. Because they were shooting on film, they had a highlight rolloff that digital still struggles to emulate. Whether it’s the soft, diffused light of a jungle canopy or the high-contrast chiaroscuro of a candlelit ceremony, the light always feels authentic. It reminds us that the best lighting tool isn’t a fixture; it’s the sun, provided you have the patience to wait for it to move.

Lensing and Blocking

The decision to shoot on 65mm negative was the most critical technical choice of the production. It wasn’t just for the resolution; it was for the presence. The 65mm negative area is significantly larger than standard 35mm, which means finer grain, better color separation, and a depth perception that feels almost 3D. As a colorist, looking at a 65mm scan is a dream the amount of data in that negative is massive.

While the lens specs aren’t always public, the look suggests high-end medium format glass (like Hasselblad or Mamiya adapted for the Todd-AO system). Wide lenses on 65mm are magical because you get that massive field of view without the distortion you’d get on smaller sensors. You can see the texture of the snow monkey’s fur and the distant peaks in the same shot with incredible clarity.

Blocking in a documentary like this is unique. You aren’t directing actors to hit a mark. You are positioning the camera to capture the “organic blocking” of real life. Fricke positioned his camera to turn daily routines into tableaus. Whether it’s a monk standing against the sky or a tribal dancer, the camera placement elevates the subject, connecting us “on a more emotional level” than a run-and-gun documentary ever could.

Color Grading Approach

For a colorist, the restoration specs of Baraka are the stuff of dreams. They didn’t just scan the 65mm negative; they oversampled it at 8K specifically 8192 pixels across. That is a staggering amount of data for a film released in 1992.

When you have a negative that dense, the grade isn’t about “saving” the image or fixing exposure; it’s about respect. If I were sitting at the wheels for this, the goal would be to preserve the photochemical DNA. You want to maintain that organic grain structure. The 8K scan gives you a pristine canvas where you can push contrast without breaking the image. You can see it in the separation of hues the red robes of monks pop against the earth tones, but they don’t bleed or clip. The restoration team could use digital tools to clean up scratches and negative damage from the “jungles of Brazil,” but the color philosophy remained faithful to the print stock. It’s about careful tonal sculpting keeping the shadows rich and the highlights rolled off smoothly rather than slapping a stylized “look” on top of it.

Technical Aspects & Tools

| Baraka – Technical Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Genre | Documentary, Nature, Drama |

| Director | Ron Fricke |

| Cinematographer | Ron Fricke |

| Editor | David Aubrey, Ron Fricke, Mark Magidson |

| Time Period | 1990s |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.20 |

| Original Aspect Ratio | 2.20, 2.39 |

| Format | Film – 65mm / 70mm |

| Lighting | Soft light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Story Location | Tokyo (Shibuya) |

| Filming Location | Tokyo (Shibuya) |

| Camera | Todd AO 65mm |

| Lens | Hassalblad Prime 65 lenses, Mamiya Large Format Lenses |

The technical backbone of Baraka is what gives it such longevity. The primary weapon was the customized 65mm camera system. This format put the film in an elite class, offering a clarity that even modern digital cinema cameras fight to match.

The restoration process, handled by FotoKem (and the team at PhotoCamp for the scan), was revolutionary. They scanned each frame individually, taking about 12 to 13 seconds per frame. With roughly 150,000 frames in the film, that is a monumental undertaking, resulting in 30 terabytes of raw 8K data. The logic was to simulate the “in-theater experience” of a 70mm print. By oversampling at 8K and then downscaling to HD or 4K for home release, they retained more detail than if they had just scanned at 4K originally.

- Also read: THE COVE (2009) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: HOW THE GRINCH STOLE CHRISTMAS! (1966) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →