Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 is that rare 1995 masterpiece that hits the sweet spot. It doesn’t just “tell” the story of the 1970 lunar mission it traps you in the capsule with them. Every time I revisit it, I’m floored by how the visual language evolves from the optimism of the launch to the suffocating tension of the “successful failure.” It’s a masterclass in how light and glass can make a historical foregone conclusion feel like a nail-biting thriller.

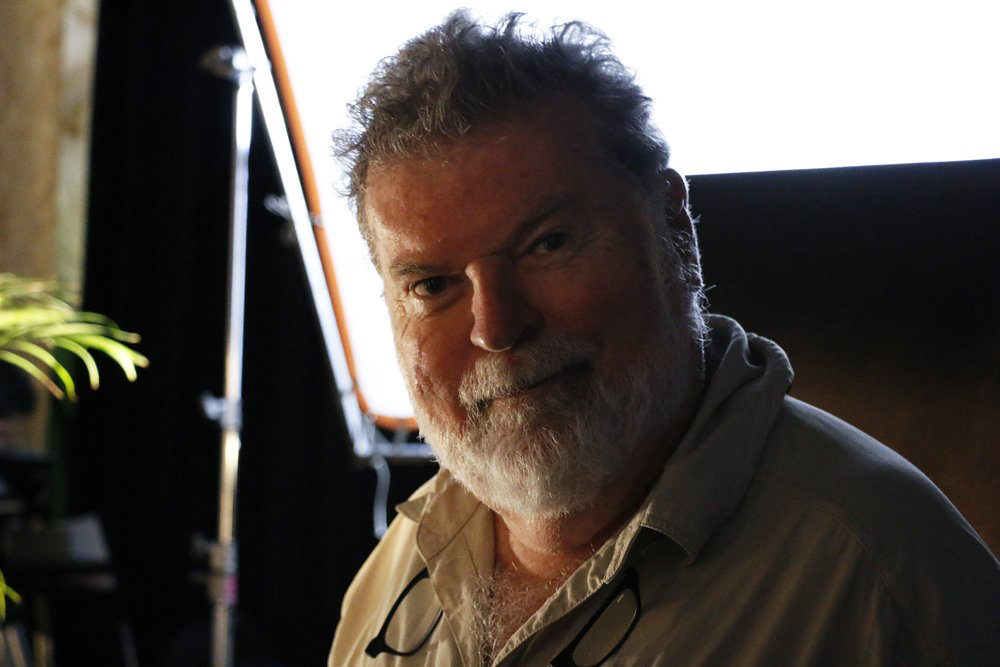

About the Cinematographer

Dean Cundey, ASC, was a fascinating choice for this. At the time, he was coming off a run of legendary genre films Halloween, The Thing, and Back to the Future. You wouldn’t necessarily peg the guy who shot Michael Myers as the first choice for a NASA docudrama, but that’s exactly why it works. Cundey brought a sense of “grounded tension” to the project. He didn’t lean into flashy, over-stylized flourishes. Instead, he used a pragmatic, precise approach that prioritized the reality of the crisis over the presence of the camera. He let the situation be the star, which is the hardest thing for a DP to do.

Technical Aspects & Tools

| Genre | Drama |

| Director | Ron Howard |

| Cinematographer | Dean Cundey |

| Production Designer | Michael Corenblith |

| Costume Designer | Rita Ryack |

| Editor | Daniel P. Hanley, Mike Hill |

| Time Period | 1970s |

| Color | Warm, Saturated, Blue |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.35 |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, Top light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light, Tungsten |

| Story Location | United States > Florida |

| Filming Location | North America > Florida |

| Camera | Panavision Platinum, Panavision Panaflex |

| Lens | Panavision Primo Primes |

| Film Stock / Resolution | 5293/7293 EXR 200T |

If you want to understand why this film looks the way it does, you have to look at the “Vomit Comet.” To get those zero-G sequences, they didn’t just use wires; they flew a modified Boeing 707 in parabolic arcs to get 23-second bursts of actual weightlessness. From a technical standpoint, that’s a nightmare for a camera crew. They were shooting on Panavision Platinum and Panaflex bodies, which are workhorses but not exactly “lightweight” in a plunging aircraft.

They opted for Panavision Primo Primes, which gave the image that crisp, high-contrast look that defines the 90s-era Panavision aesthetic. Perhaps most importantly for us color nerds, they shot on Kodak 5293 and 7293 EXR 200T film stock. That 200-speed Tungsten stock is responsible for those rich, deep blacks and the gorgeous skin tone reproduction we see throughout the Mission Control sequences. It’s a symphony of old-school precision where the gear disappears into the story.

Color Grading Approach

Let’s talk shop for a second. The grade on Apollo 13 is deceptively simple, but it’s doing a lot of heavy lifting. It’s rooted in that mid-90s print-film sensibility it’s desaturated and utilitarian, never “pretty” just for the sake of it. In Mission Control, we’re looking at a neutral, almost institutional palette. I love how the grade maintains hue separation even under those cool fluorescent sources; the skin tones stay grounded while the shadows carry a subtle cyan/green weight.

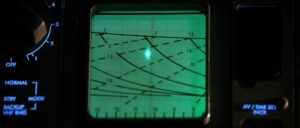

Once we’re in the crippled LM (Lunar Module), the grade shifts into “survival mode.” The palette goes almost monochromatic. We’re dealing with warm, saturated blues and deep, crushed blacks that pull the viewer into the dark with the actors. As a colorist, I really appreciate the highlight roll-off here. Even when they’re using harsh flashlights, the film stock handles the bloom with a soft, organic texture that avoids that “clipped” digital look. It’s a grade that understands its job: to make the audience feel the cold and the lack of power.

Lighting Style

Cundey’s lighting strategy is a textbook example of motivated realism. In the early stages of the mission, everything is clean, bright, and functional. It feels like the cutting edge of 1970s tech. But once the explosion hits, the lighting moves into a hard light, top-lit configuration.

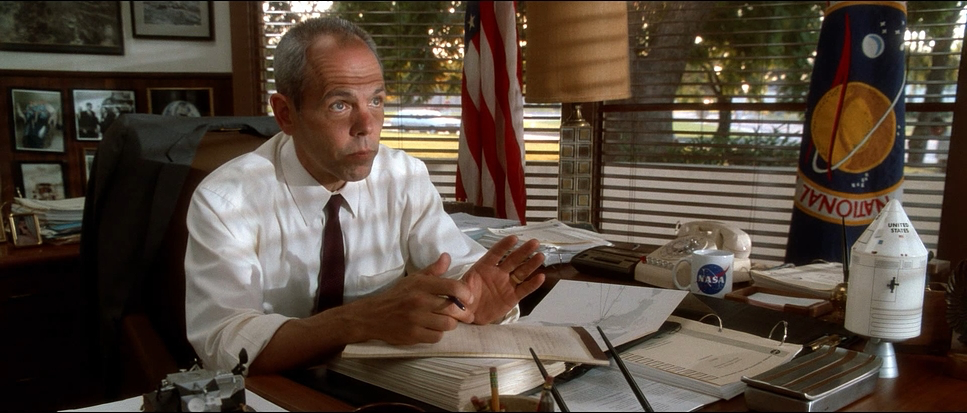

Inside the capsule, the practicals die, and the lighting becomes high-contrast and low-key. We’re talking about tungstensources, headlamps, and the meager glow of the instrument panels. This creates these deep, “thick” shadows that amplify the isolation. On Earth, Mission Control stays bathed in that institutional overhead light, but as the days pass and the stress builds, you notice the shadows under the eyes deepening. It’s a brilliant visual shorthand the light on Earth represents control, while the darkness in space represents the unknown.

Camera Movements

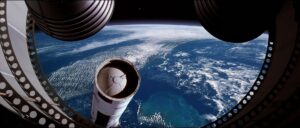

The camera in Apollo 13 has two distinct personalities. During the launch and the early mission, the movement is balletic expansive crane shots and smooth dolly moves that capture the scale of the Saturn V. It’s all about confidence and the “majesty” of space travel.

But when the “problem” arises, the camera gets twitchy. During the explosion, the frame jolts violently, creating a visceral connection to the rupture. In the zero-G scenes, the camera floats right along with Hanks, Paxton, and Bacon. It doesn’t feel like a static observer; it feels weightless. Contrast that with the “intellectual chess game” at Mission Control, where the camera weaves through consoles and pans across worried faces with a journalistic, almost documentary-style urgency. The movement mirrors the heart rate of the characters.

Lensing and Blocking

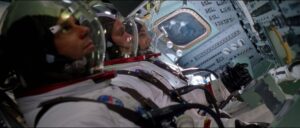

Lensing is where Cundey really guides our perspective. He uses the 2.35 aspect ratio to its full potential. On Earth, he’ll use wider glass 28mm or 35mm to show the “collective” effort of the thousands of people at NASA. But inside that tiny capsule, he moves to 50mm and 85mm Primes.

These longer focal lengths compress the space, making the environment feel even more cramped. The blocking here is a logistical miracle. You’ll often see “layered” blocking one astronaut in a tight foreground, another in the mid-ground, and a third visible through a hatch. This use of depth prevents the scenes from feeling flat, despite the fact that they’re shooting in a tin can. It’s a masterclass in how to manage a 2.35 frame in a confined interior.

Compositional Choices

Cundey’s compositions are all about the “Human vs. The Void.” Inside the capsule, the framing is tight lots of medium close-ups that emphasize the sweat and the exhaustion. He uses those small, practical windows to frame the Earth or the Moon, reminding us how far away home really is.

In Mission Control, the compositions are wider, capturing the bustling activity and the “collaborative spirit” that Ron Howard was so keen on. The iconic shot of Gene Kranz (Ed Harris) standing centrally, framed by his team, is a perfect visual metaphor for leadership under pressure. Cundey understands that composition isn’t just about making a “pretty picture”; it’s about guiding the eye to the person with the most weight on their shoulders.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The “north star” for this film was absolute authenticity. Ron Howard wasn’t interested in a “hyped-up” Hollywood version of the story. He worked closely with Jim Lovell and NASA to ensure that every toggle switch and every jolt of the spacecraft felt real.

This directive of “don’t hype it” permeated the cinematography. Cundey and Howard leaned into a documentary-like aesthetic that favored naturalism over melodrama. They pored over archival footage to match the “feel” of the 1970s without making it look like a parody. For someone like me who obsesses over “Color Culture,” this commitment to a foundational, organic look is what makes the film timeless. It doesn’t look like a “movie about the 70s” it looks like a window into 1970.

Apollo 13 (1995) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from Apollo 13 (1995). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: HALLOWEEN (1978) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: LUCKY NUMBER SLEVIN (2006) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →