Few films strip a genre down to its skeleton quite like Anatomy of a Murder (1959). For most, it’s the definitive courtroom drama, but for those of us who spend our lives behind a camera or at a grading panel, it’s something more. It is a clinic in how to use visual restraint to tell a story that is messy, morally grey, and unapologetically human.

Otto Preminger didn’t just want to record a trial; he wanted to trap the audience in the room. Alongside 12 Angry Menor Judgment at Nuremberg, this film holds a permanent spot on my shelf of “perfect” cinema. It handles volatile subject matter with a frankness that was scandalous for the late 50s, but it’s the understated eye of the cinematographer that keeps the whole thing from falling into melodrama.

Sam Leavitt: The Master of the Unvarnished

The man responsible for the look was Sam Leavitt, ASC. Leavitt wasn’t the type of DP who went looking for “the hero shot” or flashy, high-contrast stunts. His genius was much quieter. He specialized in a style that felt lived-in and organic images that didn’t feel like they were being “performed” for an audience, but rather observed in real-time.

His partnership with Preminger worked because both men valued clarity over spectacle. By choosing to shoot on location in the actual Marquette County Courthouse in Michigan, Leavitt grounded the film in a tactile reality you just can’t replicate on a soundstage. When you see the grain of the wood or the way the dust hangs in the light of that specific room, you aren’t just watching a movie; you’re a witness to the proceeding.

The Philosophy of Ambiguity

The inspiration for the look comes straight from the script’s refusal to give the audience an easy answer. The film is famously “morally ambiguous” there are no clear white hats or black hats here. Because of that, the cinematography had to remain remarkably objective.

If Leavitt had used heavy noir shadows to make the defendant look guilty, or glowing “halo” lights to make the defense look heroic, the film would have failed its own premise. Instead, he relied on the naturalism of the courthouse itself. Preminger was busy pushing the envelope of censorship with words like “rape” and “panties,” so the visual style acted as a steadying hand. It let the raw dialogue take the hits while the environment stayed grounded, silent, and heavy.

The Camera as a Silent Juror

In a movie that lives or dies on dialogue, camera movement has to be surgical. Leavitt’s camera doesn’t rush. It follows the ebb and flow of a cross-examination with the same measured pace as the law itself.

You’ll notice a lot of slow, almost imperceptible pans and tilts. My favorite moments, though, are the slow dolly pushes during a witness’s testimony. These aren’t just technical flourishes; they act like a quiet pressure. It’s as if the camera is leaning in, squinting, trying to catch the witness in a lie. Initially, you might think it’s just for dramatic gravity, but it’s deeper than that it mirrors the act of cross-examination. The camera narrows the focus until there is nowhere left for the witness to hide.

Power Dynamics and the Frame

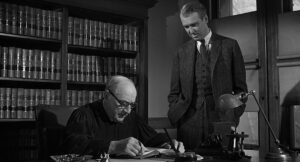

The way Leavitt composes a shot tells you exactly who owns the room. He uses the architecture of the courthouse to emphasize the physical and legal distance between the players.

When he goes wide, the deep focus keeps the jury and the spectators in the frame, reminding us that this trial isn’t happening in a vacuum. But when the heat turns up, the compositions get tight and uncomfortable. James Stewart’s Paul Biegler is often framed slightly off-center or obscured, visually signaling his status as the small-town underdog. Contrast that with George C. Scott’s Claude Dancer, who often commands the center of the frame with a calculated, “superior” coolness. The way Scott “upstages” Stewart isn’t just in the acting it’s built into the blocking and the balance of the frame.

Sculpting with “Truthful” Light

For a black-and-white film from 1959, the lighting is surprisingly soft. Leavitt understood that in monochrome, light and shadow are your only pigments. He leaned heavily into “motivated” lighting meaning the light actually feels like it’s coming from those massive courthouse windows.

This isn’t the harsh, high-contrast world of The Big Combo. It’s a softer, more “truthful” light that lets the ambiguity simmer. However, look closely at the textures: the sheen on a suit, the grain of the benches, the subtle variations of grey on the walls. Leavitt used contrast to sculpt forms and create depth without making it look artificial. Even the shadows are soft, providing visual interest rather than oppressive darkness.

Lensing, Blocking, and the Deep Focus

Leavitt mostly sticks to wide and medium lenses. This was a deliberate choice to maintain that “objective” distance. By keeping the background in focus, he ensures the courthouse and by extension, the law is always a character in the scene.

The blocking is where Preminger and Leavitt really dance. The physical arrangement of the actors tells the story of the trial. When Stewart’s character is unraveling or uncomfortable, the blocking reflects that he might physically retreat while Lee Remick invades his personal space. Even the “shady” characters like Ben Gazzara’s Lieutenant Mannion are often placed in slivers of shadow or isolated in the frame, letting the audience feel his questionable nature without the film having to say it out loud.

A Colorist’s Perspective: The Tonal Grade

As a colorist, I look at Anatomy of a Murder and see a masterclass in tonal management. Even though there’s no color, there is a “grade” a nuanced shaping of the luminance. If I were working on this film today, my job would be to protect that monochromatic poetry.

The dynamic range in the original 35mm negative is stunning. You can see detail in the brightest window highlights and the darkest corners of the room. If I were sitting at the wheels for a remaster, I’d focus on “tonal sculpting” ensuring that Jimmy Stewart’s expressive face pops against the background without looking “pasted in.” I’d resist the modern urge to crank the contrast. I’d want to keep that creamy highlight roll-off and the beautiful “milky” quality of the shadows that screams classic film stock.

The Tools of the Trade in 1959

It’s easy to forget how much work went into these images without digital sensors. Shot on 35mm (likely with Mitchell BNC cameras), achieving that deep focus required massive amounts of light and a high f-stop.

The “grade” happened in the lab, through chemistry and print lights. There were no masks or digital wheels; it was all done by feel, experience, and test prints. It was a slower, more deliberate craft. Every choice Leavitt made had to be committed to on set, which makes the consistency of the film’s look even more impressive.

Anatomy of a Murder (1959) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from Anatomy of a Murder (1959). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: SICKO (2007) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: DARA OF JASENOVAC (2020) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →