Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped (1956) is the film I keep coming back to. It’s surgical. It’s restrained. Honestly, it’s a bit of a reality check for anyone in the industry. It reminds us that visual language isn’t about the “spectacle” it’s about the logic of the frame.

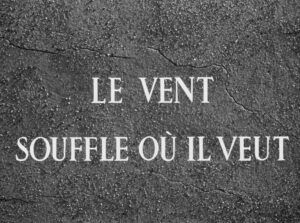

We get so caught up in the “bigger and brighter” philosophy of modern blockbusters. But this film is the ultimate antidote to that. It’s a survival story narrated through the absolute fundamentals of the craft. By giving away the ending in the title, Bresson shifts the stakes. We aren’t watching to see if Fontaine gets out; we are watching the “how.” And that “how” is a masterclass in detail, turning a sharpened spoon or a piece of rope into a monumental piece of tension.

About the Cinematographer: Léonce-Henri Burel

While Bresson’s directorial hand is famously uncompromising, we have to talk about Léonce-Henri Burel. This guy was a veteran craftsman who had been shooting since the silent era he even worked with Abel Gance on Napoléon.

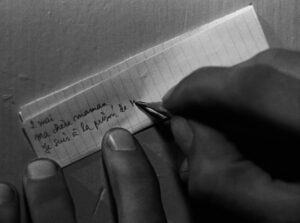

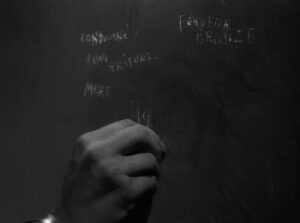

Burel wasn’t just “pointing the camera.” He was the visual architect for Bresson’s philosophy. Since Bresson preferred “models” (non-professional actors) over traditional acting, Burel’s camera had to do the heavy lifting. His job was to frame and light in a way that mirrored Fontaine’s own process: meticulous, efficient, and almost clinical. He captured those “disembodied hands” with a clarity that elevates manual labor into an act of pure human will.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The visual DNA of this film comes from one place: Bresson’s obsession with distillation. This isn’t a “glamorous” prison break. It’s an arduous, grainy, painful reality. When people call this film “clinical,” they usually mean it as a compliment to its precision.

To me, the cinematography feels rooted in French existentialism it’s all about the individual’s desire for freedom. But how do you film an abstract concept like “will”? Burel and Bresson do it by obsessing over the struggle. The camera doesn’t give you grand vistas of the prison; it gives you the grit under a fingernail and the texture of a stone wall. The visual austerity isn’t just a style choice it’s a reflection of Fontaine’s mental state. It forces us into his cell with him.

Compositional Choices

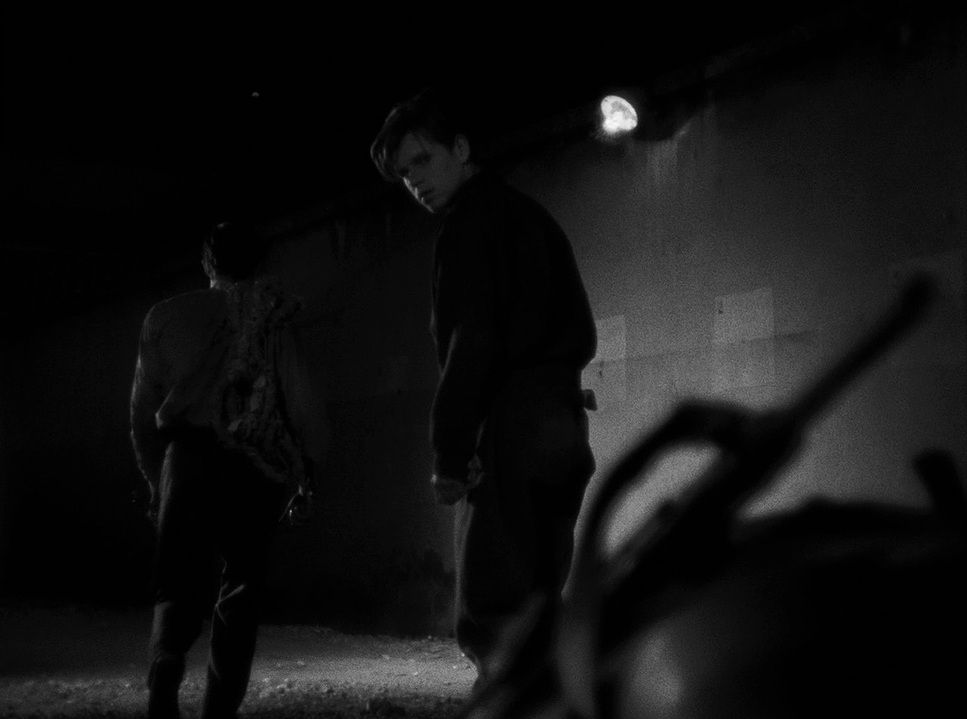

This is where the film really earns its reputation. The frames are tight and often claustrophobic. Bresson keeps us in an uncomfortable proximity to Fontaine and his tools.

Notice the repeated focus on those “disembodied hands.” We often see the work the carving, the filing without ever seeing Fontaine’s face. As a colorist and filmmaker, I’m always asking: “What is the most essential element in this frame?” Bresson answers that by isolating the essentials. A piece of wire becomes the entire world.

Interestingly, while the film feels intimate, Burel often used longer lenses to compress the space. This isn’t the wide, distorted look of a GoPro; it’s a flattened, compressed perspective that makes the prison walls feel like they’re literally pushing in on the character. Every piece of negative space feels oppressive.

Camera Movements

If modern cinema is a frantic symphony of movement, Bresson is a minimalist solo. The camera moves only when it has a damn good reason to. There are no gratuitous tracking shots or crane moves meant to show off the budget.

Instead, we get these subtle, measured pans that follow a gesture or reveal a new obstacle. When Fontaine is listening for guards, the camera stays static. It locks us into his perspective. We strain to hear the soundscape just like he does. Because movement is so scarce, when the camera does finally shift, it carries immense weight. It’s the visual equivalent of a jump scare, but driven by logic rather than a loud noise.

Lighting Style: Sculpting with Shadow

The lighting here is a masterclass in motivated realism. You won’t find a traditional three-point setup here. Burel relies on what feels like harsh, available light or at least he makes it look that way.

As a colorist, I love how he uses high contrast and deep, inky blacks. These aren’t “crushed” blacks where the detail is gone; they’re full-bodied shadows that emphasize the gloom of the cell. He uses hard, directional light streaming through those small, barred windows to create a sense of “sculpting” with shadow. There are no softboxes or flattering fills. It’s raw. The highlights are often stark, almost blown out, which perfectly captures that painful glare of the outside world that Fontaine is so desperate to reach.

Lensing and Blocking

Bresson’s blocking is dictated by the constraints of the cell. There’s no room for “acting” in the traditional sense. Everything is about economy of motion.

Burel uses that long lens approach to isolate actions within the frame. The blocking is almost mechanical like watching the gears of a clock. The camera often takes a fixed position and watches the “models” hit their marks with total precision. This creates a heightened sense of realism. You become hyper-aware of every strategic pause and every furtive glance because the camera isn’t distracting you with its own “performance.”

A Colorist’s Perspective: The “Grade”

Even though this is a black-and-white film, I still look at it through the lens of a colorist. In B&W, your “grade” is all about tonality and texture.

If I were grading this today, I’d focus on contrast shaping. You want those robust blacks to anchor the image, but you need a beautiful highlight roll-off to keep the filmic look. Burel’s grayscale is lean and neutral it avoids any warm or sepia tones that might “soften” the prison’s harshness.

The print-film sensibility is also huge here. The 35mm grain isn’t a “flaw”; it’s the texture of the story. In a modern suite, I’d be looking to preserve that organic grain structure to avoid a sterile, digital feel. It’s a visual language that matches Fontaine’s spirit: unyielding and honest.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Shot in 1956 on 35mm, the film used the staples of the era likely Arriflex or Éclair cameras. But the real “tech” story here is the editing.

There are somewhere between 100 and 150 dissolves in this movie. In Bresson’s hands, a dissolve isn’t just a transition; it’s a storytelling tool. It compresses weeks or months of waiting into a few seconds, emphasizing the sheer endurance required for the escape. When you combine that with the surgical sound design the rattle of keys, the sound of a bicycle you get a technical language that is totally cohesive. Every cut and every frame has an overwhelming sense of intentionality.

A Man Escaped (1956) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from A MAN ESCAPED (1956). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: DERSU UZALA (1975) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: TEMPLE GRANDIN (2010) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →