As a filmmaker and a full-time colorist running Color Culture, certain films pull me back into their orbit, demanding a deeper look at their craft. Ron Howard’s A Beautiful Mind (2001) is absolutely one of them. On the surface, it’s a straightforward biographical drama, but beneath that lies a profoundly intricate visual language designed to make us experience the world through the fractured lens of John Nash’s mind. It’s a masterclass in subjective filmmaking, where cinematography isn’t just about pretty pictures, but about crafting a subtle, potent distortion of reality that sweeps the audience into Nash’s internal struggle. The genius lies in how the film initially presents Nash’s delusions as concrete reality, only to pull the rug out from under us. This narrative sleight of hand is orchestrated primarily by the careful, deliberate choices made behind the camera.

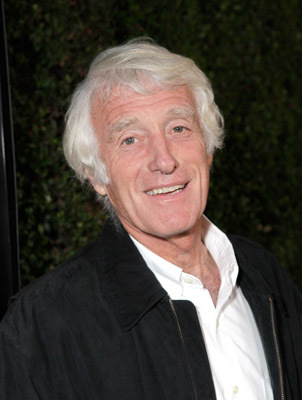

About the Cinematographer

The visual architect behind this approach is Roger Deakins. By 2001, Deakins was already renowned for an understated brilliance and a deeply psychological approach to image-making. His work rarely relies on grand stylistic flourishes; instead, he uses an almost surgical precision to convey mood through light and shadow. He’s famous for his naturalistic lighting his ability to coax incredible depth from seemingly mundane setups and his unwavering commitment to serving the story. For a film delving into the complex inner world of a genius grappling with paranoid schizophrenia, Deakins was the perfect choice. His naturalism lends an immediate credibility to Nash’s world, making the eventual reveal of his delusions shattering because they were presented with such a grounding sense of reality. We trust what we see because Deakins makes it feel real.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The core inspiration for the cinematography stems directly from John Nash’s unique internal landscape. Nash is characterized early on as a loner, obsessed with numbers and a desperate desire for greatness, trying to find mathematical patterns in everyday life. This singular focus, coupled with developing schizophrenia, presented a compelling challenge: how do you visualize the invisible? How do you depict an intellect simultaneously constructing and deconstructing its own reality?

Howard and Deakins made the bold decision to portray Nash’s world entirely from his point of view, immersing the audience in his perception without warning. The objective was to place the audience in Nash’s shoes, victimized by the same distortion of reality. This meant crafting a visual language that felt authentic even when depicting the unreal. The subtle hints woven throughout the first half the slightly off-kilter introductions of characters like Charles, Marcy, and Parcher were designed to sow seeds of unease without betraying the big reveal. The cinematography had to be clever, almost conspiratorial, in leading us down Nash’s path.

Camera Movements

The camera movements in A Beautiful Mind are a testament to Deakins’s restrained elegance, serving to amplify Nash’s internal state. Early in the film, during Nash’s time at Princeton, the movements are precise and observational. There’s a quiet grace to the way the camera tracks him through bustling university halls, often singling him out amidst a crowd, emphasizing his intellectual isolation even as he seeks connection. This measured approach anchors us in what we believe to be objective reality.

However, as Nash’s paranoia escalates, the camera shifts subtly. It rarely becomes overtly shaky in a clichéd “madness” way; instead, the unease manifests through unsettling applications. Consider the moments when the imaginary agent Parcher first appears the camera’s slight delay, or a pan revealing him standing in places where he couldn’t have just arrived. The “spy thriller” sequences feature rapid, almost frantic movements mimicking Nash’s panic. It’s often not a grand, sweeping crane shot designed to impress, but a carefully considered move that places us right in Nash’s bewildered headspace. Even when the camera is static, precise framing in moments of high tension, like Nash being forcibly sedated, conveys inescapable claustrophobia.

Compositional Choices

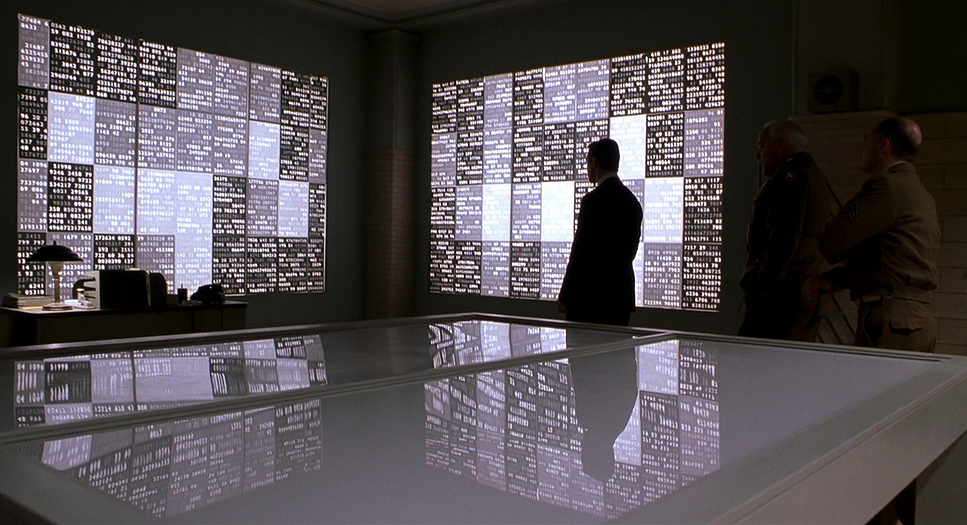

Deakins’s composition is incredibly deliberate, often communicating Nash’s state without dialogue. From the outset, Nash is framed in ways that underscore his solitude. Wide shots in grand academic settings often swallow him, emphasizing his smallness in the face of vast intellectual challenges, yet also his profound loneliness. He’s often positioned slightly off-center, isolated in the frame a visual metaphor for his social awkwardness and mental isolation.

The introduction of his imagined companions uses composition subtly. When William Parcher first appears, he’s partially concealed, almost like a figure emerging from the periphery of Nash’s subconscious. Similarly, the way Charles is framed sometimes appearing suddenly, or exiting a room through a door that doesn’t quite behave correctly creates a subliminal sense of unreality. The film also uses depth cues masterfully. In crowded scenes, Nash might be sharply focused in the foreground with the background blurred, isolating him. Conversely, when his paranoia intensifies, compositions become layered with elements suggesting hidden figures or surveillance, deepening our shared sense of unease.

Lighting Style

Deakins’s lighting is characteristic of his naturalistic, motivated approach, meaning light sources feel plausible even when crafted for emotional effect. In the early university scenes, there’s often a warm, scholarly glow evoking intellectual vibrancy. This almost idealized lighting contributes to the initial believability of Nash’s delusions.

As Nash’s journey turns darker, the lighting shifts. His “secret assignments” take on a cooler quality, leaning into shadows that suggest espionage. However, an important technical note here is the use of “flashing” the film negative a technique where the film is exposed to a weak, uniform light before development. This doesn’t create harsh, deep blacks; rather, it lifts the shadows slightly, lowering overall contrast and desaturating the image subtly. It creates a slightly hazy, period feel that beautifully mirrors a mind where the edges of reality are blurring. It’s hardly ever a harsh look; it feels like natural light filtering through blinds in a dusty office, or muted streetlights at a clandestine meeting. Conversely, scenes with his wife Alicia, representing reality and love, often feature a softer, warmer, more embracing quality of light.

Lensing and Blocking

The choices of lensing and blocking are nuanced, working in concert to shape our perception. Interestingly, the production relied heavily on Cooke S4/i lenses, alongside Zeiss Super Speeds. Cookes are famous for the “Cooke Look”—a warmth, roundness, and gentle rendering of skin tones. Using these lenses for a story about paranoia is a brilliant counter-intuitive choice; their inherent warmth helps ground the delusions, making them feel safer and more “filmic” than cold reality.

Deakins utilizes these lenses to support the blocking of imaginary characters. The way Parcher is blocked—he just is there, a seamless part of Nash’s world is reinforced by integrating him into the frame rather than isolating him with heavy shallow depth of field. I often think about how cinematographers choose between wider lenses for context versus longer lenses for psychological compression. While a long lens might seem obvious to isolate a paranoid character, Deakins often uses wider focal lengths in close-ups. This brings us intimately into Nash’s space without feeling invasive, while still allowing the environment to remain in context—suggesting that Nash’s surroundings are an inextricable part of his perception, real or imagined.

Color Grading Approach

As a colorist, I connect deeply with this film’s visual strategy. A Beautiful Mind was finished photochemically in 2001, meaning the “look” was baked into the negative through stock choice, lighting, and lab processes like flashing, rather than created in a digital grading suite. The palette is generally desaturated, leaning into cooler tones for academic and suspenseful sequences. This isn’t a harsh, digital desaturation, but a soft, organic look inherent to the film flashing process.

Because the negative was flashed, the shadows aren’t crushed black holes; they have a milky, lifted quality. When Nash is immersed in delusions, the color feels muted a world internally vivid to him but lacking the full spectrum of external reality. The tonal sculpting is subtle. The highlight roll-off characteristic of film lends a slightly ethereal quality to brighter parts of the image, blurring the line between reality and hallucination. The crucial counterpoint is the warmth introduced in scenes featuring Alicia representing her grounding influence. This isn’t a dramatic shift, but a gentle migration within the overall desaturated framework.

Technical Aspects & Tools

A Beautiful Mind — Technical Specs

| Genre | Drama, Romance, Mental Health, History, Biopic |

| Director | Ron Howard |

| Cinematographer | Roger Deakins |

| Production Designer | Wynn Thomas |

| Costume Designer | Rita Ryack |

| Editor | Daniel P. Hanley, Mike Hill |

| Colorist | Mike Milliken |

| Time Period | 1950s |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.85 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm – Flashing |

| Lighting | Soft light, Side light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Story Location | … New Jersey > Princeton |

| Filming Location | … United States > New Jersey |

| Camera | Arri 435 / 435ES, Arri 535 / 535B, Moviecam SL |

| Lens | Cooke S4/ i, Zeiss Super Speed |

| Film Stock / Resolution | 5279/7279 Vision 500T, 5293/7293 EXR 200T, 8582/8682 F-400T |

Shot in 2000-2001, this was an entirely film-based production. Deakins employed ARRIFLEX 535 and 435 cameras paired with the aforementioned Cooke and Zeiss lenses. He utilized Kodak Vision stocks—likely 500T (5279) for interiors and slower stocks like EXR 200T (5293) for exteriors chosen for their fine grain and latitude.

The film’s visual texture the grain structure, the beautiful highlight roll-off, and the organic way shadows render are direct results of these photochemical choices. The latitude of film allowed Deakins to capture detail across a broad dynamic range, crucial for scenes oscillating between natural light and shadow. The post-production involved a traditional film optical workflow. These technical choices were not arbitrary; they formed the very foundation of the film’s immersive visual language.

- Also read: THE SIXTH SENSE (1999) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: JURASSIC PARK (1993) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →