On April 21st, 2024, that Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. officially hit its centenary. A hundred years. Let that sink in. As a colorist running Color Culture, obsessing over shadow density and LUTs, yet I often find myself looking back at 1924 wondering how the hell they pulled this off without a single pixel to hide behind.

Revisiting this for its anniversary isn’t just a nostalgia trip; it’s a required masterclass. At a lean 45 minutes, the “laughs per minute” ratio is higher than almost anything coming out of Hollywood today. But beyond the gags, it’s a masterstroke of visual audacity that still baffles modern cinematographers.

About the Cinematographer: The Unsung Elgin Lessley

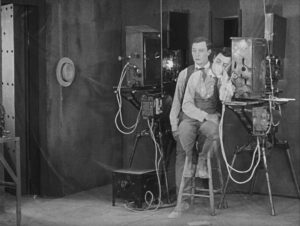

We usually credit Keaton’s genius alone and he deserves it, considering he directed, edited, and did his own death-defying stunts but we need to talk about his “ace” cameraman, Elgin Lessley (along with Byron Houck). Lessley was a technical wizard.

While modern directors have a safety net of “we’ll fix it in post,” Lessley and Keaton were playing a high-stakes game of physical geometry. They weren’t just “filming”; they were inventing the language of the camera as they went. Their partnership was less a traditional director-DP relationship and more like two mad scientists conspiring to break the laws of physics on a 35mm strip.

Camera Movements: Silence is Motion

In the 1920s, cameras were basically heavy furniture. Movements were rudimentary because the gear was a nightmare to move. Yet, Sherlock Jr. feels incredibly dynamic.

Take the iconic motorcycle sequence. They didn’t have stabilized gimbals or Russian arms. The camera acts as a raw, unflinching witness. By keeping the frame wide and the camera relatively static or platform-mounted, they let the internal movement dictate the energy. It’s a lesson in restraint: sometimes the most high-octane thing you can do is just lock the tripod and let the actor risk their life in a perfectly composed wide shot.

Compositional Choices: The “Frame within a Frame” Trick

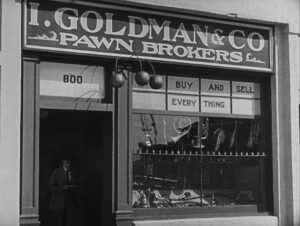

The composition here isn’t just about looking “pretty” it’s functional. Keaton uses a recurring “frame within a frame” motif that is pure genius.

You see it early on when he’s watching his rival through a door. It’s a subtle visual primer for the film’s legendary centerpiece: the dream sequence where he walks into the cinema screen. By establishing these layers of “reality” through deep-focus composition, the transition from the “theatre” to the “movie” feels seamless. It’s a masterclass in using depth cues to tell a story without a single line of dialogue.

Lighting Style: Sculpting with Silver

Back then, lighting was mostly about getting enough exposure for slow film stocks. It was utilitarian. But look closer at the theater sequences.

The lighting in the projection booth has a gritty, motivated feel before shifting into the more “ethereal” high-key look of the dream world. If I were grading this today, I’d be looking at how that artificial light from the projector defines the space. Even in a black-and-white medium, the contrast isn’t just “on or off.” They were using light to separate Keaton from the backgrounds, ensuring his physical comedy popped despite the desaturated palette.

Lensing and Blocking: The Power of the Wide

They leaned heavily on wider glass likely a “long lens” by 1920s standards but wide enough to keep everything in deep focus. Why? Because you can’t fake a stunt in a wide shot.

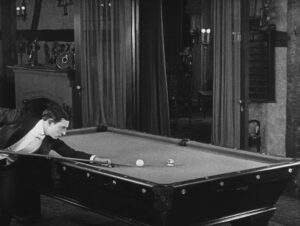

The blocking is essentially a ballet. Every movement by Keaton and his cast is frame-perfect. Look at the billiard scene. That isn’t clever editing; that’s Keaton’s vaudeville training meeting a perfectly positioned camera. The lens stays wide so you can see the “impossible” ricochets happen in real-time. It forces the audience to believe their eyes.

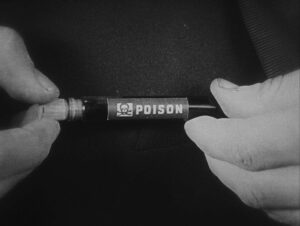

Technical Aspects & Tools: No CGI, No Excuses

The “walk into the screen” effect is still a miracle of in-camera matte work. No green screens, just double exposures and precise timing.

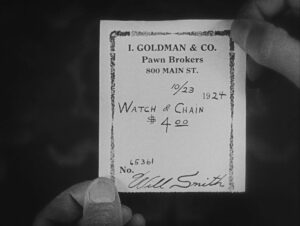

And then there’s the suitcase trick a vaudeville carry-over involving a trap door and a second actor. It’s pure practical-effects genius. But the most “technical” part of the film? Keaton actually broke his neck during the water tower stunt and didn’t even realize it for nine years. That’s the kind of “technical commitment” you just don’t see anymore. He famously scrapped an earlier cut of the film because it didn’t get enough laughs, proving that for all his technical wizardry, he was a storyteller first.

Color Grading Approach: The Tonal Spectrum

As a colorist, looking at a 1924 35mm print is a unique challenge. You aren’t “grading color” you’re sculpting luminance.

If this landed on my desk in DaVinci Resolve today, I’d be obsessing over the highlight roll-off. Digital sensors tend to clip whites harshly, but this film has a beautiful, luminous glow in the highlights that I’d want to preserve. I’d use tonal sculpting to ensure Keaton’s pale face and dark clothes stay separated from the California sun in the backgrounds. It’s about simulated hue separation: using the grayscale to create depth where color doesn’t exist. I’d also be careful not to “over-clean” the grain. That texture is the soul of the film.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography: A Poem to the Movies

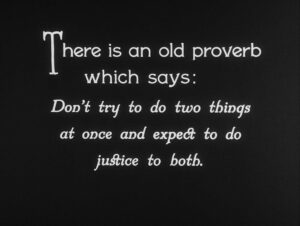

The core of Sherlock Jr. is really just a love letter to the medium itself. Keaton understood that the camera wasn’t just a recording device; it was an enabler of “magical realism.”

The dream structure gave him a hall pass to be as surreal as he wanted. It allowed him to marry his stage-gag sensibility with cinematic tricks that only work on film. He was chasing the “impossible,” using the dream logic to push the boundaries of what a camera could (and should) do.

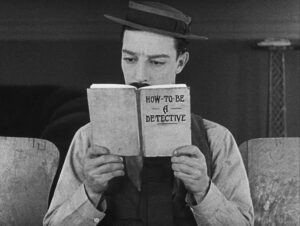

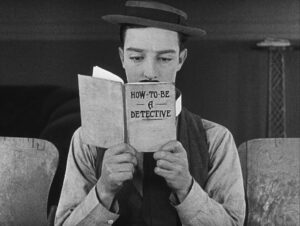

Sherlock Jr. Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from Sherlock Jr. (1924). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: NEON GENESIS EVANGELION: THE END OF EVANGELION (1997) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: BLACKFISH (2013) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →