Lars von Trier’s Dogville (2003) is exactly that a film that burrowed into my consciousness the moment I saw it. It’s polarizing, sure, but for me, it’s a masterclass in how radical visual choices can actually amplify a narrative rather than distract from it.

When I first sat down with it, I was floored by its audacity. It takes a sledgehammer to traditional set design, forcing us to look past the “stuff” on screen and confront the raw, unsettling core of the characters. It’s the kind of project that reminds me why I got into this craft in the first place: to find new ways to communicate through nothing but light, shadow, and intent.

About the Cinematographer

The visual architect here was Anthony Dod Mantle. His work with von Trier has always been a bit of a playground for innovation, often pushing the boundaries of what film can be through the lens of Dogme 95 principles. While Dogvilleisn’t technically a Dogme film, that spirit of austerity and “no-frills” authenticity is baked into its DNA.

Mantle is famous for that raw, handheld, vérité energy think of the kinetic chaos in Slumdog Millionaire or the gritty digital textures of 28 Days Later. But in Dogville, he does a total 180. He’s still dynamic, but he’s operating within a black box. His camera isn’t just observing; it’s performing. It forces us to engage with the theatricality of the space while somehow making the whole thing feel intimately cinematic. It’s a huge testament to his versatility.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

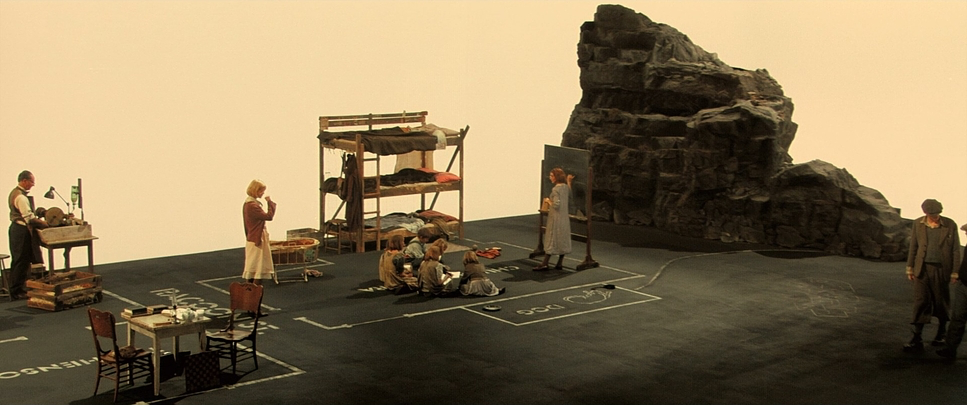

The most striking thing about Dogville is, obviously, the absolute rejection of realism. Von Trier shot this in a “black box” studio in Sweden, using white chalk lines to signify where walls and streets should be. Instead of physical structures, we get abstract outlines. The gooseberry bushes were literally just chalk drawings with the word “Gooseberry” written inside. It’s a concept so bold that it immediately breaks your brain as a viewer.

Von Trier pulled from everywhere: the chapter synopses of Winnie the Pooh, old English novels, and Trevor Nunn’s theatrical adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby. These aren’t just trivia points; they are the anchors for the film’s visual grammar. The lack of physical sets is a giant hint to the audience: don’t take this literally.

For me, this wasn’t about a budget constraint; it was a profound artistic statement. By stripping away the walls, the filmmaking forces us to confront these people and their moral rot in a clinical way. It’s not about where they are, but who they are. The town of Dogville becomes a philosophical testing ground—an arena for human nature, exposed under a spotlight.

Camera Movements

In a world where walls don’t exist, camera movement becomes the primary narrator. The camera guides our eyes, reveals spatial relationships, and dictates the emotional temperature of every scene.

Take that initial wide, overhead shot that establishes the “map” of Dogville. It’s a God’s-eye view, likely achieved with a meticulously operated crane or a motion control rig. It sets a tone of detached observation, as if we’re looking at a playbill or a dollhouse. But as the story moves on, the camera gets right into the dirt. We get tracking shots following Grace (Nicole Kidman) as she navigates these imaginary streets, pushing past invisible doors. There’s a paradox here: the camera has total freedom to move through “walls,” yet the story is about Grace’s increasing entrapment. It emphasizes that in Dogville, there is no privacy. Everyone is always watching, and the camera acts as a relentless spotlight that never lets her hide.

Compositional Choices

Composition in Dogville is fascinating because it operates in a void. Without traditional depth cues like architecture or a horizon line, the visual emphasis shifts entirely to the actors. As some critics have noted, the focus is incredibly heavy on the characters; it grabs you and forces you to take in the performance instead of getting distracted by a pretty background.

You’d think an open set would make the frame feel flat or two-dimensional, but it actually does the opposite. It elevates blocking and lighting to a structural level. The characters’ positions relative to each other and to those chalk lines define the space. The vast blackness surrounding the town isn’t just empty space; it’s a palpable presence. It’s isolation. It’s the moral emptiness of the community. When Grace is humiliated, the framing often leaves her tiny against that black canvas, making her look incredibly vulnerable.

Lighting Style

Lighting this must have been an intellectual puzzle. How do you motivate light when there are no windows or sky? The answer is a theatrical approach delivered with cinematic subtlety.

Dod Mantle uses a stark, high-contrast style to sculpt the characters. He employs directional key lights to mimic sunlight streaming through “windows,” creating sharp shadows on the floor. This hard light adds a layer of rawness that reflects the harsh reality Grace is living through. When she first arrives, the light has a certain delicate, almost “angelic” quality. But as things go south, the lighting becomes unforgiving, throwing her face into partial shadow and highlighting her confinement. It’s a masterclass in creating an atmosphere out of thin air.

Lensing and Blocking

Blocking in Dogville is essentially a choreographed dance of perceived space. Actors have to interact with phantom doors and invisible objects with total precision. This isn’t just a gimmick; it’s a metaphor for the arbitrary social rules that govern the town.

From a lensing perspective, Mantle uses the full toolkit. He needs wide glass to capture the expansive “map” of the stage, but when the screws start to turn on the characters, he moves to standard or longer focal lengths. These tighter lenses compress the space, drawing us into their internal states. The camera’s ability to “ghost” through walls without obstruction is a practical freedom that makes every lens choice feel intentional. Because there are no physical barriers, a simple shift in focal length can completely change our sense of intimacy or isolation.

Color Grading Approach

This is the part where I really geek out. As a colorist, Dogville is a prime example of grading as narrative. It’s not about making things “pretty” it’s about shaping perception. The look is distinct: desaturated, high contrast, and feeling a bit like a treated old photograph.

If I were handling this in the DI suite, my first priority would be contrast shaping. We need those blacks to be deep and inky, with the white chalk lines etched sharply against them. This isn’t just for “punch”; it visually represents the moral binaries of the story. I’d also be looking at the highlight roll-off. We want to keep detail in the highlights to avoid a “cheap digital” look, ensuring that even under intense spotlights, the skin textures feel real.

There’s also some subtle hue separation happening. I’d likely favor Grace’s skin tones, giving her a slightly warmer, more naturalistic feel to contrast with the cooler, clinical tones of the townspeople. And since this was shot on the Sony HDW-F900, the grade had to work hard to give it a print-film sensibility. We’re talking about adding subtle grain and managing shadow response to mimic photochemical film. The grade mirrors Grace’s journey: we start with a hint of warmth and neutrality, but as her despair grows, we push toward a colder, harsher, and more desaturated palette.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Dogville | 2.39:1 • Sony F900 • Digital Tape

| Genre | Crime, Drama, Thriller, Satire, Comedy, Melodrama |

| Director | Lars von Trier |

| Cinematographer | Anthony Dod Mantle |

| Production Designer | Peter Grant |

| Costume Designer | Manon Rasmussen |

| Editor | Molly Malene Stensgaard |

| Colorist | Fabien Pascal, Dan Konzior |

| Time Period | 1930s |

| Color | Warm, Desaturated |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.39 – Spherical |

| Format | Tape |

| Lighting | Hard light, Side light, Edge light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light |

| Story Location | Colorado > Dogville |

| Filming Location | Trollhättan > Film i Väst, Nohab Industrial Estate |

| Camera | Sony DSR-PD150 Mini DV, Sony F900 / HDW-F900 |

Dogville was a massive early win for digital cinematography. It was shot on the Sony HDW-F900, one of the first HD cameras used for a major feature. It also utilized the Sony DSR-PD150 (Mini DV), which added to that raw, experimental texture.

Shooting early digital was a tightrope walk. The dynamic range was nothing compared to what we have now, so Dod Mantle had to be incredibly precise with his high-contrast lighting. In the color suite, managing noise in those deep blacks would have been a constant battle. Even the audio was a challenge imagine recording clean sound on an echoey, open stage where actors are moving through multiple “rooms” at once. Dogville is a reminder that technical limitations don’t have to be a hurdle; if you’re creative enough, they become the solution.

- Also read: YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN (1974) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: JFK (1991) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →