Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another (2025) with more than just a casual interest. When you hear “PTA,” “VistaVision,” and “DiCaprio” in the same sentence, you know you aren’t just getting a movie; you’re getting a masterclass in format.

The chatter surrounding this release has been predictably polarized some calling it a cinematic triumph, others dismissing it as a morally bankrupt “Hollywood circle jerk.” For me, the noise doesn’t matter. What matters is the visual DNA. This isn’t just an action-thriller; it’s a tightrope walk where the cinematography is the invisible hand steadying the pole, navigating a complex 2010s California landscape with a precision that only 35mm film can provide.

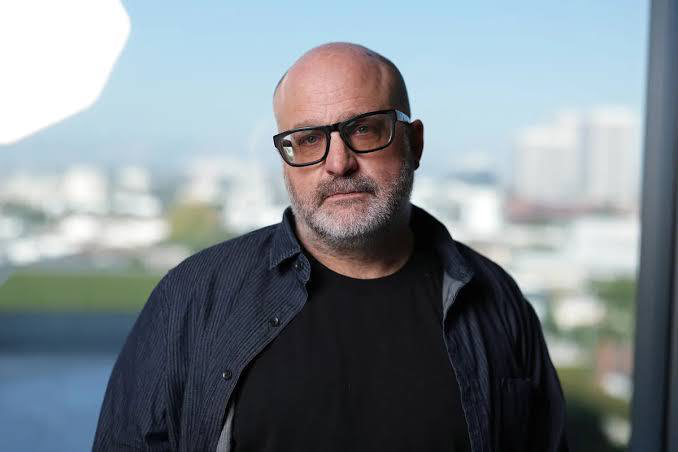

About the Cinematographer

In a PTA film, the cinematography is an act of co-authorship. For One Battle After Another, Anderson teamed up with Michael Bauman, a choice that marks a fascinating evolution in his filmography. Bauman, who has worked in the PTA camp for years (notably as a lighting tech/gaffer), steps into the DP role with a profound understanding of how to ground the extraordinary in “raw realistic humanity.”

The shift here is palpable. We’ve moved away from the “Pynchonian surrealism” of Inherent Vice and into a space that feels startlingly immediate. Bauman’s work here demands more than technical proficiency; it requires an intuitive empathy. He manages to transform a scene from a high-stakes spectacle into an intimate revelation, using the camera to breathe alongside the characters a balancing act that makes the absurd feel alarming because it is stripped of all digital embellishment.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The core inspiration for the film’s look seems to be the reconciliation of two disparate realities: the mythologized fervor of a revolutionary past and the pathetic, yellow-hued present of Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio). This isn’t a nostalgic gaze; it’s a contemporary re-evaluation of the “failed 60s” replanted into the “immediate contemporary now.”

Visually, this translates into a grounded, almost unromantic aesthetic. The filmmakers have stripped away the surrealism in favor of an observational mode. The “conceit of watching relatively normal people crash against their various madness” is inherently visual how do you frame an “ordinary schlubby loser single dad” in a situation that is fundamentally ungrounded? The answer lies in a documentary-style realism mixed with the nerve-racking tension of a kidnapping thriller. It’s an aesthetic that anchors the extraordinary in a deeply felt, albeit uncomfortable, human experience.

Camera Movements

The camera movements in One Battle After Another are the engine driving its shifting tones. Given the blend of a “chase movie” and a “humanistic story,” Bauman utilizes a deliberate mix of techniques. For the high-stakes sequences, we see fluid, controlled movements that maintain clarity without devolving into the “shaky-cam” chaos so common in modern action.

However, to portray Bob as a “schlubby loser” whose ambition outruns his ability, the camera often adopts a more vulnerable posture. During his moments of disarray like when he’s struggling to remember “militant action training passwords” the camera work feels more immediate, reflecting his physical exertion and internal mess. During the confrontations with Sean Penn’s Colonel Lockjaw, the camera isolates the intensity, focusing on a man on the verge of either exploding or weeping. Every pan and tilt serves a singular purpose: to escalate tension or deepen our understanding of a character’s failing resolve.

Compositional Choices

The film’s compositions are a subtle tool used to highlight the dissonance between expectation and reality. For Bob, the “single dad” who isn’t really the “main character of reality,” the frames are often left-heavy and wide. Framing him against the indifferent California landscape emphasizes his isolation and his diminished status. This use of negative space makes his “best effort” feel genuinely resonant.

Conversely, for Lockjaw, the compositions are rigid and imposing. The scenes involving the “super-secret white supremacist organization” utilize claustrophobic frames, often with characters obscured by foreground elements to suggest a shadowy, creeping influence. For Charlene, the daughter, we see a visual evolution—starting as a character being “protected” in the frame to one who occupies a more central, prepared position as her independence emerges.

Lighting Style

In line with the commitment to “raw realistic humanity,” the lighting style is heavily motivated and naturalistic. This isn’t a film of high-contrast shadows; instead, Bauman utilizes soft light and low contrast to create a specific atmosphere.

For much of the film, we see an overcast daylight quality that feels authentic to a California afternoon. It’s a choice that avoids the “action movie” tropes of harsh chiaroscuro. Instead, the soft, even light underscores the absurdity of the situation. It’s “creeping police state” meets “mundane reality.” This approach allows the audience to absorb the uncomfortable truths on screen without the lighting “telling” them how to feel, making the moments of sudden violence feel even more jarring.

Lensing and Blocking

This is where the technical choices get truly exciting. Shot on the Beaumont VistaVision camera, the film utilizes a massive 35mm frame that offers a unique depth of field and texture. The lens kit is a “who’s who” of legendary glass: Panavision Primo Primes, Super Speed Zeiss MKIIs, and PVintage Ultra Speeds.

The use of wide lenses on a VistaVision sensor allows for a 1.78 aspect ratio that feels immersive. It allows the environment to swallow Bob whole. Blocking is paramount here; Bob is often blocked clumsily, moving with the physical awkwardness of an “out of shape” dad thrust into a “militant” role. Contrast this with Lockjaw’s assertive, space-dominating blocking. The chemistry between Bob and Charlene is reinforced through their physical proximity they are often framed in clean singles that emphasize their shared vulnerability in an indifferent world.

Color Grading Approach

As a colorist, I found Gregg Garvin’s work on the grade to be the film’s secret weapon. The palette is distinctly warm, desaturated, and yellow. This isn’t the “warmth” of a sunset; it’s a jaundiced, slightly oppressive heat that perfectly captures the “paranoid drug-addicted” headspace of the protagonist.

The decision to keep the contrast low while leaning into yellow hues provides a consistent tonal sculpting that unites the satire and the drama. The skin tones remain natural but carry that specific 2010s California “haze.” By avoiding vibrant, hyper-real colors, Garvin ensures the film feels lived-in. The grade transitions seamlessly between the levity of the “satire” and the gravity of the “nerve-racking” plot points, using hue separation to suggest the sterility of the police state against the earthier, yellowed world of our “schlubby” hero.

Technical Aspects & Tools

One Battle After Another (2025)

Technical Specifications: 35mm VistaVision • 1.78:1 Spherical

| Genre | Action, Comedy, Crime, Drama, Family, Fatherhood, Thriller |

| Director | Paul Thomas Anderson |

| Cinematographer | Michael Bauman |

| Production Designer | Florencia Martin |

| Costume Designer | Colleen Atwood |

| Editor | Andy Jurgensen |

| Colorist | Gregg Garvin |

| Time Period | 2010s |

| Color | Warm, Desaturated, Yellow |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light, Low contrast |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Overcast |

| Story Location | USA > California |

| Filming Location | USA > California |

| Camera | Beaumont VistaVision Camera |

| Lens | Panavision Primo Primes, Panavision Super Speed Zeiss MKII, Panavision System 65 Lenses, Panavision Ultra Speed II (PVintage), Panavision | Standard Primes |

The decision to shoot on 35mm film using the Beaumont VistaVision system is the foundation of the film’s success. While many would have defaulted to an ARRI Alexa for a contemporary thriller, PTA and Bauman chose the organic grain and superior color rendition of celluloid.

The technical foundation here isn’t about “flash” it’s about providing an invisible framework. The use of Panavision System 65 and Ultra Speed lenses provides a beautiful, organic texture that digital sensors still struggle to emulate. In the DI (Digital Intermediate) process, managing the uncompressed scans from 35mm allows for a level of highlight roll-off and shadow detail that makes the “soft light” aesthetic truly sing. Every detail, from the desperation in Bob’s eyes to the vast California fields, is rendered with cinematic fidelity that feels both massive and human.

- Also read: CODA (2021) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: NAUSICAÄ OF THE VALLEY OF THE WIND (1984) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →