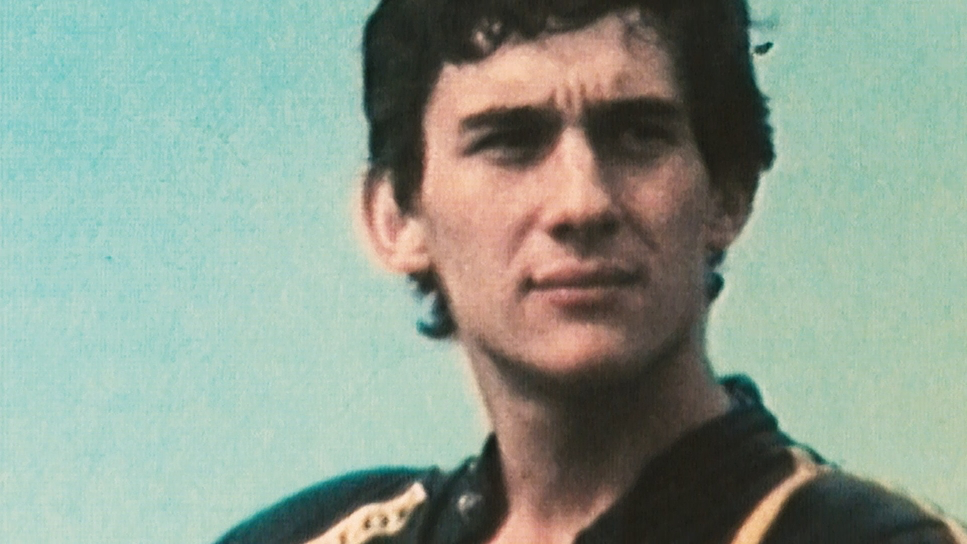

As a filmmaker and colorist running Color Culture, I watch a lot of documentaries, but Asif Kapadia’s 2010 film hits differently. It’s not just a great sports movie; it is a lesson in how curation is cinematography. Watching it is an emotional heavy lift for me, reaffirming how found visuals—even grainy, imperfect ones—can connect an audience to a subject faster than the most polished 8K footage. I remember watching it and feeling like I was physically inside the cockpit,vibrations and all.

The film makes a radical commitment: zero talking heads, no contemporary interviews on camera. Every single frame is archival. That isn’t just a style choice; it’s the engine of the film. It forces you to engage with Senna’s world in the present tense, without the safety net of hindsight. It’s like looking through a window in a time machine.

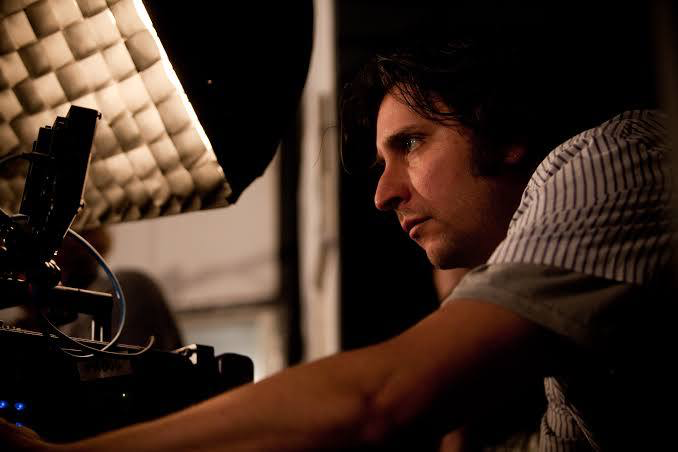

About the Cinematographer

This section usually profiles a specific Director of Photography, but Senna is unique. While Jake Polonsky is technically credited as cinematographer—likely for capturing the contemporary audio interviews and specific B-roll elements—the true “visual authors” were the editorial team: director Asif Kapadia, editor Chris King, and producer James Gay-Rees.

They operated as visual archaeologists. Their job wasn’t to light a set; it was to chisel a narrative out of thousands of hours of existing footage. Kapadia has spoken about gaining access to Bernie Ecclestone’s massive Formula 1 archive, which was essentially a vault of racing history. But the real gold wasn’t the broadcast footage; it was the personal tapes. Senna’s brother, Leonardo, provided home videos from university breaks and family holidays. These tapes weren’t broadcast quality—they were shaky and raw—but that lack of polish is exactly what makes them work. It strips away the “legend” and shows you the human being.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The guiding philosophy here was simple but difficult to execute: tell the story strictly from Senna’s point of view. Kapadia wasn’t interested in a history lesson; he wanted a psychological immersion.

The team noticed a distinct visual parallel in how Senna spoke. In English interviews, he was guarded and professional. In Portuguese, speaking to his own people, he was spiritual and philosophical. The filmmakers mirrored this. They contrasted the rigid, formal framing of the broadcast interviews (the public persona) with the loose, handheld chaos of the home videos (the private soul). By restricting the visuals to the period, they removed the “documentary distance.” You don’t feel like you are studying the 80s; you feel like you are surviving them alongside him.

Camera Movements

Since the footage is archival, the “camera movements” weren’t directed for this movie—they were selected. And the selection creates a specific rhythm of speed and anxiety.

- Onboard Cameras: These are the MVP shots. The vibration, the rolling shutter artifacts, and the sheer violence of the image inside the cockpit tell you more about F1 than any commentary could. When Senna is navigating Monaco, you physically feel the lack of grip.

- Trackside Pans: These long lens pans compress the background and exaggerate the speed. It’s a classic broadcast technique, but in this context, it emphasizes the sheer velocity of the era.

- Helicopter Shots: These act as a breather. They give you geographical context and scale, offering a moment of release before plunging you back into the chaos of the track.

- Pit Lane Zooms: In the broadcast feeds, the camera operators often did slow, creeping zooms into the drivers’ helmets. The editors weaponize these zooms, using them to isolate Senna’s eyes right before a race, catching moments of fear or intense focus that were originally just filler TV shots.

Compositional Choices

The editorial team made smart decisions about which compositions to hold on to.

- Tight Close-Ups: Essential for the psychological angle. We spend a lot of time searching Senna’s eyes through his visor. These shots isolate him, visually reinforcing his status as an outsider fighting the establishment.

- Wide Shots for Context: The film uses wide shots of the grandstands and the “circus” of F1 to show the scale of the machine Senna was up against.

- The Gladiatorial Angle: The race footage often favors low angles looking up at the cars/drivers, giving them a mythic, larger-than-life presence.

- The “Amateur” Frame: The family footage is often framed imperfectly—heads cut off, slightly out of focus, off-center. A traditional DP might call this a mistake; here, it’s a texture. It feels unposed and unguarded, which is the only way to get the audience to let their guard down, too.

Lighting Style

You can’t talk about “lighting design” in Senna the way you would for a narrative feature. The lighting wasn’t designed; it was endured.

- Hard Sunlight: The high-contrast, harsh sun of Brazil or Monaco serves as a visual baseline. It’s distinctively “video” looking—blown-out highlights and crushed blacks—which grounds the film in reality.

- The Grey Diffused Light: The most dramatic scenes happen in the rain. The flat, low-contrast lighting of wet tracks like Donington ’93 creates a gloomy, oppressive atmosphere. The way the grey sky reflects off the wet tarmac creates a specific, metallic texture that makes the cars look like sharks in water.

- Motivated Sources: Every light source is real. The sodium vapor lights of a night event, the fluorescent hum of a press conference room—it’s all motivated by the environment. It feels unmanipulated, which helps the audience trust that the emotions they are seeing are real, too.

Lensing and Blocking

- Lensing: The film is a collision of optical textures. You have the massive telephoto lenses of the TV cameras,which compress space and make the cars look like they are inches apart (amplifying the danger). Then you have the wide, fixed-focus lenses of the onboard cameras and the consumer camcorders. The shift in lens characteristics—from the clinical sharpness of a broadcast lens to the chromatic aberration of a home video lens—subliminally tells the viewer which “mode” of Senna we are watching: the public icon or the private man.

- Blocking: Obviously, nobody told Senna where to stand. But the editors selected footage where the physical positioning tells the story.

- Dominance: We often see Senna’s car isolated in the frame, far ahead of the pack. The visual distance does the storytelling.

- Confrontation: In the rivalries with Prost, the film selects angles that show them physically cutting each other off or standing shoulder-to-shoulder but refusing to make eye contact. The physical space between them becomes a character in the scene.

Color Grading Approach

This is where I really geek out. The grade for Senna (handled by Colorist Paul Ensby) wasn’t about making a “pretty” picture; it was a massive technical challenge of unification. You are dealing with a nightmare of mixed formats: 16mm film, 35mm film, Betacam, U-matic, and noisy VHS.

A colorist’s approach here has to be forensic.

- Gamma Mapping & Normalization: The first hurdle is that video and film handle light differently. Video clips highlights instantly; film rolls them off. Ensby likely had to map the gamma curves of the video sources to try and match the response of the film sources, softening that harsh “digital video” clip to make it feel more organic.

- Film Emulation: To glue it all together, a film emulation process (likely a Print Film Emulation LUT) was almost certainly applied. This adds a cohesive “density” to the colors. It helps the cheap video footage punch above its weight by aligning its color palette with the cinematic 35mm footage.

- Signal Noise vs. Film Grain: There’s a difference between digital noise (ugly) and film grain (pleasing). The grade involves managing the noisy VHS channels, likely denoising the chroma channel to stop the color from “bleeding,” but keeping the luma noise (or adding a layer of uniform grain) so the texture feels consistent across the timeline.

- Tonal Storytelling: The grade shifts emotionally. The early days in karting are often warmer, sunnier. As the rivalry with Prost heats up and the politics intervene, the palette seems to cool down, becoming more clinical. The tragic weekend at Imola is desaturated, heavy on the greys and cyans, emphasizing the foreboding atmosphere.

Technical Aspects & Tools

| Senna (2010) – Technical Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Genre | Documentary, Action, History, Biopic, Drama, Sports |

| Director | Asif Kapadia |

| Cinematographer | Jake Polonsky |

| Editor | Chris King, Gregers Sall |

| Colorist | Paul Ensby |

| Time Period | 1990s |

| Color | Saturated, Blue |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 |

| Lighting | Low contrast |

| Lighting Type | Daylight |

| Story Location | Victoria, Melbourne |

| Filming Location | Victoria, Melbourne |

The backend work on this film was a beast.

- Upscaling & Restoration: A huge part of the pipeline was taking Standard Definition (SD) signals and upscaling them for theatrical release without making them look like plastic. This requires high-end hardware scalers (like Teranex) or software restoration tools (like DaVinci Resolve’s Neural Engines) to hallucinate detail that isn’t there,while carefully preserving the artifacts that give the footage its character.

- Audio Reconstruction: Visually we see the car, but the audio is often a reconstruction. The sound team had to remix the mono or stereo TV audio into a 5.1 surround experience, layering in clean recordings of the V10 and V12 engines to give the audience that visceral, chest-thumping bass that the original tapes lacked.

- The Edit Suite: Handling this amount of mixed-framerate footage (25fps PAL, 29.97fps NTSC, 24fps Film) in an NLE like Avid or Premiere is a technical headache. The conform process alone—ensuring every frame plays back smoothly without ghosting—is a testament to the technical team’s rigor.

Senna proves that you don’t need a RED camera or an ARRI Alexa to make something cinematic. It’s a film that was “written” in the edit suite and “photographed” by history. For a colorist, it’s the ultimate reminder that our job isn’t just to make things look good—it’s to make things feel true.

- Also Read: CAPERNAUM (2018) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also Read: WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION (1957) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →