To really understand visual language, I often have to step back and look at the masters. And when it comes to Billy Wilder’s 1960 masterpiece, we are looking at a goldmine.

It’s one of those films that resonates deeply, feeling surprisingly modern even six decades later because its observations on human behavior and corporate life are timeless. But beyond the genius script—which rightly gets most of the praise—the cinematography is a quiet, powerful force. It meticulously crafts the film’s emotional landscape. It is a masterclass in visual storytelling, and I’d argue the visuals are an equal partner to the writing in the film’s enduring success.

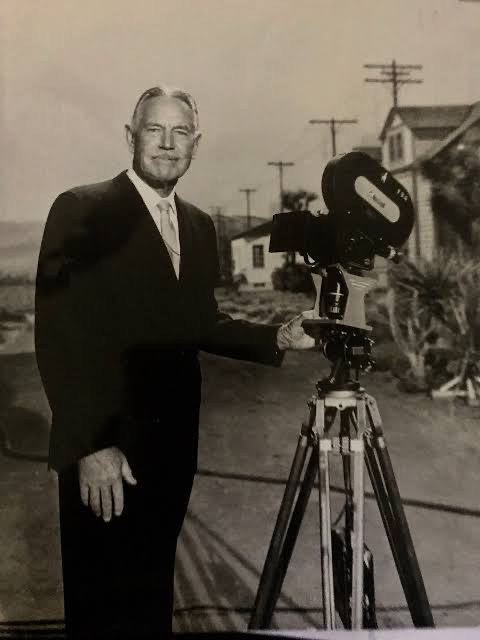

About the Cinematographer

The man behind the lens for The Apartment was Joseph LaShelle. If you’re a student of classic Hollywood, his name should spark recognition. LaShelle was an absolute wizard with black and white, known for crafting images that were both stark and deeply expressive. He won an Oscar for Laura (1944), another monochrome gem, and his work consistently demonstrated a keen eye for atmospheric lighting and precise composition.

For a film like The Apartment, which delves into moral ambiguity and personal loneliness within a sprawling, impersonal corporate world, LaShelle was the perfect choice. He understood how to use shadow and light to convey subtext, making him an ideal collaborator for a director like Wilder, who believed in respecting the audience’s intelligence by showing, not just telling.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The visual inspiration for The Apartment springs directly from the film’s core themes: isolation amidst a crowd and the dehumanizing scale of corporate life. There is a hidden world beneath the surface of respectability here—the office where everyone is posturing, and the apartment where the real, often messy, human behavior happens. LaShelle’s cinematography needed to reflect this dichotomy.

Wilder’s insistence on visual storytelling meant the camera had to do heavy lifting. Consider the vast, open-plan office where Jack Lemmon’s Bud Baxter works. It’s depicted as an endless line of desks with people “slugging away,” looking like a school of salmon swimming upstream. This imagery captures the visual reality LaShelle created: endless rows of identical desks and a sea of anonymous faces. The cinematography here isn’t about beauty; it’s about a brutal, almost documentary-like precision in depicting the mundane, repetitive nature of this environment. It anchors the lonesome atmosphere of the “big winter city,” establishing the urban jungle that breeds Bud’s peculiar predicament.

Camera Movements

In The Apartment, camera movements are rarely flashy, but they are always purposeful. They serve the narrative, subtly guiding the eye. Early on, the extensive tracking shots through the labyrinthine corridors and the massive office floor are crucial. They establish the sheer scale of “Consolidated Life of New York,” making Bud Baxter, our “junior executive,” feel tiny and insignificant. These dollying shots aren’t just for exposition; they are depth cues emphasizing the overwhelming bureaucracy and the vastness of the system Bud is trying to navigate.

Later, as the narrative becomes more personal, the movements become intimate. A slow push-in highlights Fran Kubelik’s increasing despair, while a gentle dolly alongside Bud emphasizes his growing affection—or his profound loneliness. Even when two characters are just talking, LaShelle uses subtle re-framing to emphasize shifts in power or emotion. It’s never about drawing attention to the camera itself, but rather allowing it to be a silent, observant participant. This commitment to unobtrusive, emotionally resonant movement is a hallmark of classic Hollywood, and it’s something I strive for in my own work—finding the movement that feels right for the emotional beat, rather than just moving the camera because I can.

Compositional Choices

This is where The Apartment truly shines. LaShelle’s compositional choices are masterful, using negative space and blocking to tell Bud’s story. The initial wide shots of the office are iconic, immediately communicating the dehumanizing scale of the corporation. Thousands of desks, each a tiny island in a sea of beige, illustrate how Bud is just a small cog in a giant machine. These compositions are oppressive, making us feel Bud’s anonymity and the rigid structure governing his life.

Inside Bud’s apartment, the visual language evolves. Initially, the space feels empty, cold, and impersonal—a commodity to be traded. But as Fran comes to occupy it, and as Bud begins to reclaim it, the compositions soften. We see tighter frames, often emphasizing faces or small details. LaShelle frequently uses doorways and windows as natural frames within the frame, reinforcing Bud’s sense of confinement or his longing for connection.

When Fran is recovering in Bud’s apartment, the framing often places her small and vulnerable in a large bed, emphasizing her fragility. The blocking is equally telling: the boss, Sheldrake, often appears dominant, framed higher or centrally, while Bud is frequently pushed to the side, looking up, or boxed in by his environment. It’s character revealed through visual placement.

Lighting Style

For a black and white film, lighting is everything, and LaShelle’s work here is exceptional. He uses a classic Hollywood style but with a nuanced approach that transcends mere glamour. The lighting is heavily motivated, meaning it feels naturalistic even when meticulously sculpted.

In the office, the lighting is bright and almost stark, mimicking the harsh reality of fluorescent overheads. It’s functional, not flattering, emphasizing the cold nature of the corporate environment. By comparison, the apartment often features a more intimate, lower-key lighting style. When Bud is alone, the apartment can feel quite dark, reflecting his isolation. But during moments of connection, especially with Fran, the lighting warms and softens. The scene where Bud cares for Fran after her suicide attempt is a perfect example: gentle chiaroscuro plays with highlights and shadows to sculpt their faces, conveying the emotional weight of the moment. This contrast—harsh and public versus soft and private—allows the audience to intuit the characters’ internal states without a single line of dialogue.

Lensing and Blocking

Lensing and blocking work hand-in-hand here to define relationships and space. LaShelle frequently employs wider lenses, especially in the office scenes, to create deep focus. This allows for multiple planes of action to remain sharp, inviting the audience to take in the vastness of the corporate machine. It respects the intelligence of the viewer by giving them a rich visual field to explore rather than forcing their eye with shallow depth of field. This deep focus often facilitates background gags or subtle character moments, enriching the world without drawing overt attention.

For intimate scenes, the lenses tighten slightly, focusing on the emotional beats. But the blocking remains the consistent strength. The precise arrangement of actors within the frame continuously informs the audience. Think of the power dynamics inherent in how Sheldrake sits at his desk, towering over Bud, or how Bud might shrink into the corner of his own apartment when it’s occupied by an executive. The infamous scene where Fran reveals her broken mirror is a prime example of blocking and lensing working together: the focus is on her vulnerability and the small, intimate detail of the shattered reflection—a visual setup that pays off beautifully.

Color Grading Approach

Now, this is where I put my “colorist” hat on. While The Apartment is monochromatic, the principles of grading—contrast shaping, tonal sculpting, and dynamic range—are absolutely paramount. We are just applying them to luminance values rather than hue. If I were grading this film today, my focus would be on meticulously shaping its grayscale palette.

Contrast Shaping: LaShelle’s work is fantastic here, but a contemporary grade would further refine it. I’d want to ensure robust black levels that still retain detail, preventing them from crushing into pure nothingness unless it’s for a specific dramatic effect. The whites would need to be bright and clean, but with a beautiful, controlled highlight roll-off—that smooth transition from bright areas to mid-tones that is the hallmark of well-exposed film. This prevents a harsh, clipped digital look and preserves the “magic” of the analog aesthetic.

Tonal Sculpting: Black and white isn’t just “grayscale”; it’s a rich spectrum. I’d carefully manipulate these mid-tones to add dimension. For instance, the corporate office might benefit from a slightly cooler, flatter mid-tone response to emphasize its starkness, while Bud’s apartment could have warmer, richer grays to evoke a sense of interiority. The goal is to enhance the luminance contrast to guide the eye and emphasize textures, making up for the absence of hue separation.

Dynamic Range Decisions: The beauty of film stock from that era (likely something akin to Eastman Double-X) is its impressive dynamic range. A modern grade would ensure this captured range is fully expressed. I’d make subtle adjustments to preserve detail in the deepest shadows and the brightest highlights, ensuring the image feels full and rich, never sparse or flat. The subtle grain of the film, too, would be preserved to maintain that authentic, organic texture.

Technical Aspects & Tools

The Apartment – Technical Specifications

| Genre | Comedy, Rom-Com, Satire, Drama, Political, Romance, Holidays, Workplace |

|---|---|

| Director | Billy Wilder |

| Cinematographer | Joseph LaShelle |

| Production Designer | Alexandre Trauner |

| Costume Designer | Forrest T. Butler, Irene Caine |

| Editor | Daniel Mandell |

| Time Period | 1950s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.35 – Anamorphic |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light, Top light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light, Fluorescent |

| Story Location | … New York > Manhattan |

| Filming Location | … Manhattan > 2 Broadway, Manhattan, New York, United States |

| Lens | Panavision Auto Panatar, Panavision Lenses |

To achieve its distinctive look, The Apartment relied on the robust tools of its time. The film stock was almost certainly a panchromatic black and white stock, known for fine grain and excellent tonal rendition. The cameras were likely Mitchell BNCs—heavy, incredibly stable beasts that produced rock-solid images, perfect for smooth dolly shots.

The lenses would have been classic Cooke Speed Panchros or Bausch & Lomb Baltars. While not as clinically “sharp” by modern standards, these lenses are beloved for their beautiful, organic rendering and gentle focus fall-off. They contribute significantly to that timeless look, delivering images with character rather than digital perfection.

Lighting instruments would have been a mix of large Fresnel lights for controlled pools of light and open-face units for broad washes. Lighting for black and white is a unique art; without color to differentiate subjects, cinematographers must “paint with light.” LaShelle’s ability to define space and character through this mastery of light is a testament to his craft.

- Also Read: INCENDIES (2010) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also Read: TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD (1962) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →