When this movie first hit US screens in a truncated, re-ordered version, it was rightfully panned. But once Leone’s original vision was restored with its non-linear, dreamlike structure intact it ascended to its place as a cinema classic. The film’s brilliance lies in its visual contradictions: it renders “disgraceful characters” with a lyrical, exquisite touch. That tension between the ugly truth of the characters’ lives and the sublime artistry of their depiction is where the cinematography truly shines.

About the Cinematographer

The visual architect behind this work was the legendary Tonino Delli Colli, a frequent collaborator with Leone who also shot The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West. Delli Colli brought a painterly quality to the screen, transforming barren landscapes and gritty urban spaces into canvases of dramatic expression. His partnership with Leone was symbiotic. For Once Upon a Time in America, Delli Colli had to translate Leone’s complex vision of memory and time into a coherent visual language, navigating different eras without losing the film’s overarching melancholic logic. He realized Leone’s intention to “know every look” before a single frame was exposed.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Leone described the film as unfolding “like a dream,” a directive that dictated the cinematography. The narrative constantly shifts between Noodles’ present (1968), his youth in the 1920s, and his adult years in the late 1930s. This non-chronological storytelling is the film’s beating heart. The camera work, lighting, and composition facilitate a subjective journey through memory.

The inspiration was internal the fragmented, unreliable nature of human memory, tinged with nostalgia and pain. The cinematography evokes feelings rather than merely depicting events; it shows us how Noodles remembers his past, not necessarily how it objectively happened. This manifests in lingering shots and specific lens choices that create a sense of distance or intimacy, underscoring the emotional weight of every scene.

Camera Movements

Leone and Delli Colli employ camera movements with a deliberate, almost balletic precision. Long, lingering shots allow the audience to absorb the detailed mise-en-scène and the characters’ internal states. This isn’t just slow pacing; it’s a visual echo of Noodles’ own rumination.

When the camera moves, it’s often in slow, controlled dollies or elegant crane shots that reveal vast urban landscapes or intimately track characters. The sweeping crane shot over the Manhattan Bridge in the 1920s showcases the gang’s youthful ambition against a burgeoning metropolis. However, there are also moments of dizzying, disorienting movement designed to destabilize the viewer. These subjective choices subtly mirror Noodles’ fractured mental state. A slow push-in on a character’s face, holding long enough to force us into their thoughts, becomes a signature technique less about spectacle, and more about psychological immersion.

Compositional Choices

Delli Colli’s compositions masterfully utilize depth and negative space. He frequently employs deep focus, allowing multiple planes of action to exist simultaneously, which establishes the bustling, layered world of Prohibition-era New York. This gives the audience a rich sense of context even as the narrative weaves through personal memories.

Close-ups are used sparingly but powerfully. Delli Colli captures the nuances of Robert De Niro’s micro-expressions with intimate framing, often using shallow depth of field to isolate his face against a soft background. This draws our focus entirely to the quiet turmoil within. Conversely, wider shots frame characters within expansive, often oppressive environments, emphasizing their smallness against the indifference of the world. The framing often isolates characters even when they are physically together, hinting at the ultimate solitude of their choices particularly in the complex friendship between Noodles and Max.

Lighting Style

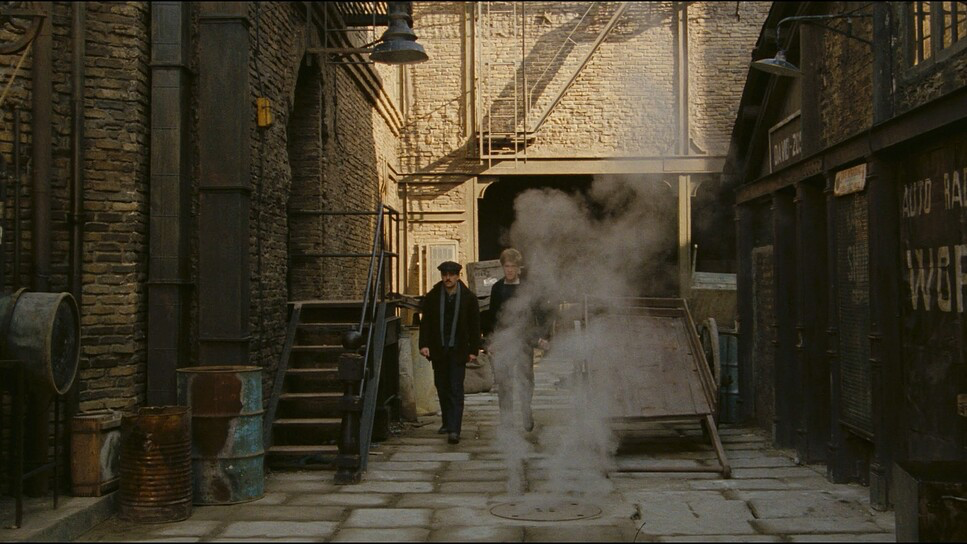

The lighting in Once Upon a Time in America acts as a character itself. Delli Colli leans heavily on motivated lighting, grounding the period settings in a gritty realism using visible practicals lamps, streetlights, and windows. However, he elevates this with a stylized approach that supports the film’s dreamlike tone.

Golden hour is heavily featured in the childhood flashbacks, bathing scenes in a warm glow that evokes a bittersweet memory of innocence. This warm diffusion suggests a longing for a past that, while violent, held moments of genuine friendship. Conversely, scenes set in the later years feature harsher, higher-contrast lighting with deep shadows. This chiaroscuro effect creates a sense of foreboding appropriate for the moral murkiness of their adult lives. Dynamic range decisions are critical here; the film retains rich detail in the shadows while preserving nuance in the highlights. The way light spills through a window to catch dust motes is meticulously crafted to immerse us in the emotional stakes.

Lensing and Blocking

Delli Colli’s lens choices are integral to the film’s visual perspective. The use of anamorphic lenses provides that characteristic wide aspect ratio and oval bokeh, lending a cinematic grandeur. The wide frame allows for expansive compositions that convey the scope of the story while maintaining intimacy.

Telephoto lenses are deployed to compress space, bringing background elements visually closer to the foreground to emphasize fate or inescapable pressure. Blocking is equally precise. In intense confrontations between Noodles and Max, medium close-ups create a physical proximity that belies their growing emotional distance. In scenes of violence, the blocking is shockingly direct, placing the audience uncomfortably close to the action. The tragic love story between Noodles and Deborah is often blocked with subtle physical barriers—tables, doorways—that visually underscore the fracture in their relationship.

Color Grading Approach

For a colorist, Once Upon a Time in America is a masterclass in period emulation. The restoration highlights the inherent characteristics of the original Kodak Vision stocks specifically the forgiving highlight roll-off and the density of the grain structure, which digital sensors still struggle to replicate authentically.

The grade relies heavily on contrast shaping. Delli Colli wasn’t afraid of crushing the blacks to ground the gritty reality of the gangster genre, but he maintained a remarkable separation in the mid-tones to keep facial performances readable. The hue separation is equally deliberate: the warm, amber tones of the 1920s flashbacks aren’t just a filter; they feel baked into the emulsion, contrasting sharply with the desaturated, cooler blues and grays that define the 1968 timeline. Skin tones are rendered with a slight warmth that lends humanity even to ruthless characters. It’s a “dirty” palette in the best way possible grounded, textured, and devoid of the pristine, sterile look of modern digital capture.

Technical Aspects & Tools

| Genre | Adventure, Crime, Gangster, Mafia, Drama, Epic |

|---|---|

| Director | Sergio Leone |

| Cinematographer | Tonino Delli Colli |

| Production Designer | Giovanni Natalucci |

| Costume Designer | Gabriella Pescucci |

| Editor | Nino Baragli |

| Time Period | 1930s |

| Color | Warm, Saturated |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, Side light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light |

| Story Location | … New York > Lower East Side |

| Filming Location | … United States > New York |

| Camera | Arriflex 35 BL4 |

Shot on 35mm film using Arriflex cameras, the choice of emulsion imparted a fine grain structure and natural color rendition. While specific filter choices aren’t explicitly documented, it is likely that diffusion filters were used in flashback sequences to soften the image, while color correction filters on the lens helped push the warm or cool tones in-camera, laying the groundwork for the final look.

The reconstruction efforts re-incorporating nearly 20 minutes of material from work prints—speak to the dedication to preserving Leone’s vision. This process involved not just editing but extensive color timing to ensure consistency between the restored footage and the original negative. As a colorist, I deeply appreciate this; it’s about more than making the footage look “good” it’s about preserving the emotional integrity of the original exposure.

- Also read: PRINCESS MONONOKE (1997) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: HOWL’S MOVING CASTLE (2004) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →