If there’s one film that gets under my skin not just as a filmmaker but specifically when looking at the image pipeline it’s John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982). This isn’t just a horror movie; it is a textbook example of visual efficiency, a slow-burn descent into paranoia made manifest through density, shadow, and frame.

When it first dropped, the film faced a cold reception. Critics initially recoiled from its visceral practical effects and bleak, nihilistic ending, labeling it a critical and commercial failure. They saw it as too dark, too gory. But time has been incredibly kind. It found its footing on home cinema, slowly clawing its way into the pantheon of beloved cult classics. Today, it is rightly re-evaluated as one of the best horror movies ever made. It’s a film that lives in your head, a suffocating embrace of dread, and the bulk of that power comes directly from its cinematography.

For those of us who spend our days shaping images, The Thing is a benchmark. It demonstrates how every visual decision from the broadest composition to the most subtle tweak in a highlight builds an inescapable atmosphere. It reminds us that true horror isn’t just what you see; it’s what you feel from the way it’s shown.

About the Cinematographer

Behind the lens for this chilling work was Dean Cundey, a name synonymous with some of Carpenter’s most iconic imagery. Cundey’s collaboration with Carpenter is legendary, bringing a distinct visual language to films like Halloween and Escape from New York. He understands how to craft suspense not just through shocking imagery, but through the meticulous control of visual information.

Cundey’s genius here lies in his ability to ground the fantastical in a gritty, documentary-like reality. He doesn’t shy away from the grotesque, but he frames it with a restraint that amplifies the terror. A perfect example is his subtle use of “eye lights.” Cundey specifically lit the human characters with a faint gleam in their eyes; if that gleam was missing, it was a subtle visual cue that the character might be the Thing. It’s a tiny, almost imperceptible detail especially in the blood test scene but it subconsciously cues the audience to feel safe, or terrified. That is the kind of technical nuance that makes his work here so enduring.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

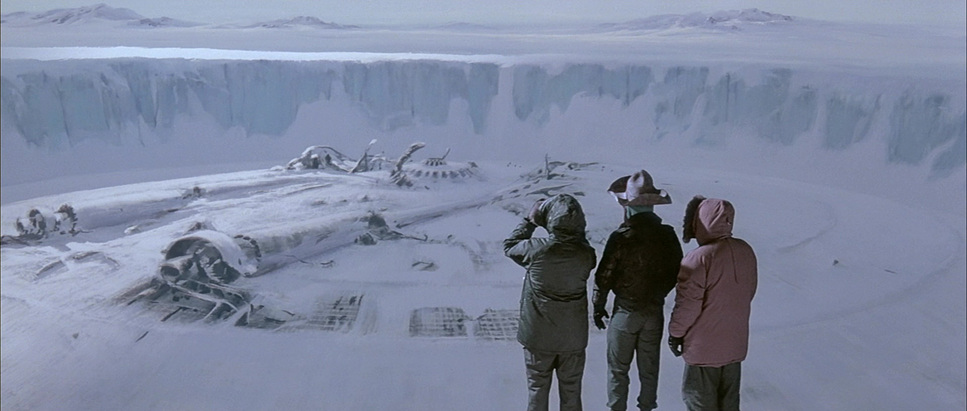

The core inspiration for The Thing‘s visual language is, without a doubt, its central themes: isolation, paranoia, and the primal fear of the unknown. The story of American scientists trapped in an Antarctic research base, infiltrated by an alien shapeshifter, screams for a specific kind of visual treatment. It is a collision of sci-fi, claustrophobia, and body horror, all sitting in a hostile, frozen environment.

The Antarctic setting isn’t just a backdrop; it’s an antagonist. The vast, unforgiving white expanse outside the base accentuates the desperate confinement within. There’s nowhere to run. This environmental claustrophobia is key. The production actually chilled the filming stage to a bone-numbing 40 degrees Fahrenheit (approx 4°C). The intent was to make the actors genuinely look and feel cold. This wasn’t just about method acting; it was a deliberate choice to infuse the visual fabric of the film with discomfort. When you see Kurt Russell’s breath, or the subtle shivers of the cast, it’s genuine. That physical discomfort becomes part of the film’s texture.

Drawing from the novella “Who Goes There?” and the 1951 film The Thing from Another World, Carpenter’s vision amplified the psychological torment. Cundey’s camera was the perfect instrument to translate that vision. The horror isn’t just external; it’s internal, reflected in every suspicious glance and shadowed corner.

Camera Movements

Cundey’s approach to camera movement in The Thing is defined by controlled restraint. It’s rarely flashy, but always purposeful. We often see long, slow tracking shots through the base’s narrow corridors. These aren’t just establishing shots; they emphasize the labyrinthine nature of the confinement. The movements place us within the space, making us feel that tight, suffocating pressure. The camera becomes a voyeur, allowing the tension to build through sustained takes.

Then there are the moments of abrupt, almost violent motion, usually triggered by an explosion of practical effects. These sudden shifts from serene (or terrifyingly static) observation to chaotic handheld movement effectively jolt the audience. Carpenter understands the rhythm of editing knowing exactly how long to hold a shot to let the silence hang heavy before creeping in. The camera might linger on a character’s face, letting paranoia etch itself onto their features, before cutting to a wider shot that reveals the chilling isolation. It’s a dance between revealing just enough and hiding the rest.

Compositional Choices

Composition is a crucial tool for conveying the film’s themes. Wide shots of the Antarctic wilderness swallow the tiny research base, emphasizing its utter insignificance against a hostile planet. We see figures silhouetted against endless snow, dwarfed by the environment. Inside the base, however, the framing becomes incredibly tight.

Cundey frequently uses deep focus compositions, allowing multiple planes of action to exist within a single frame. Characters in the foreground, mid-ground, and background are all in focus, heightening the feeling that anyone could be the Thing. It reinforces the paranoia by making it visually impossible to isolate one person as trustworthy. We are constantly scanning the frame, looking for tells.

Take the early scenes with the Norwegians. Their incomprehensible warnings are visually reinforced by their gear. The Norwegian pilot wears goggles with tiny eye sockets, making him impossible to connect with because we can’t see his eyes. This simple compositional choice immediately introduces suspicion and throws us off balance. Furthermore, Cundey uses negative space and strong diagonal lines to create tension. Long, empty corridors are bisected by shadows, leading the eye into an unknown void. The computer, representing the alien calculation, is often framed coldly against McCready’s frustrated, human response a visual representation of the biological chess match at play.

Lighting Style

The lighting in The Thing serves as a narrative device to evoke cold and dread. Cundey leans into a low-key, high-contrast style that suits the bleak environment. Interior scenes are often dimly lit, relying on practical sources like overhead fluorescents, bare bulbs, or the glow of computer screens. This motivated lighting grounds the film in a tangible reality.

Shadows are active elements of menace here, swallowing corners and obscuring details. This ambiguity is crucial for a monster that mimics its prey. It makes every darkened doorway a potential threat. The harsh, cool light that dominates the film reflects the sub-zero temperatures, emphasizing the chill.

When a flame appears a flamethrower, an explosion, or a flare it bursts with a violent, primal orange. This creates a stark contrast to the otherwise sterile blues and grays. Usually, warm tones signify comfort, but here, they signify destruction—the only way to combat the alien. That subtle “eye light” mentioned earlier is the counterpoint to this; a tiny spark of life amidst the gloom, serving as a hidden narrative clue about identity.

Lensing and Blocking

Cundey’s lensing choices contribute significantly to the psychological unease. He often employs wider anamorphic lenses in confined spaces. This doesn’t just open the room up; it exaggerates the depth, making the corridors feel endless while introducing subtle distortion at the edges. When the Thing transforms, these lenses amplify the grotesque forms, pushing the body horror into a surreal space. Conversely, for moments of surveillance, longer lenses compress the space, giving a voyeuristic feel as if we are trying to decipher who is human from a distance.

Blocking is where the performance of paranoia comes alive. Characters are frequently shown in tight groups, yet with physical barriers between them. The blood test scene is the standout example: each man is tied down, observed by McCready. The camera’s attention to their individual reactions is key. We see Palmer staring at the floor with a smirk, while others look intently at McCready. This blocking choice is a powerful visual cue that hints at his true nature before the explosive reveal.

Similarly, the separation of Norris and Palmer, who hang back during the chase for Windows, subtly reinforces the idea that the Things operate with a shared agenda. This blocking reflects the disintegrating trust among the crew—the visuals telling the story before the dialogue does.

Color Grading Approach

From a grading perspective, The Thing is a gem of the photochemical era. Its palette is predominantly cool, dominated by steely blues, desaturated grays, and sterile whites. This creates a foundation of oppressive coldness that is difficult to emulate perfectly in modern digital workflows without it feeling synthetic.

Against this cool floor, intense saturated reds and oranges erupt the blood, the fire, the explosions. These vibrant hues act as emotional shocks. When the Thing unleashes its transformations, the deep, visceral reds of the gore are pushed hard, separated from the cooler background tones to maximize impact. This contrast shaping ensures the horror is inescapable.

The tonal sculpting is equally impressive. The shadows are deep, often with a subtle blue or green push, enhancing the mystery. Highlights particularly the snow and practical lights roll off organically. This filmic roll-off creates a softer, atmospheric quality even in the brightest areas, retaining texture. The grain structure, especially in the underexposed interiors, adds a tactile, gritty feeling to the picture. It isn’t over-polished. It’s raw, and that texture serves the narrative. The hue separation between the cool ambient light and the warm, terrifying explosions is a masterstroke of color strategy.

Technical Aspects & Tools

The Thing (1982) – Technical Specifications

| Genre | Horror, Mystery, Science Fiction, Thriller, Cosmic Horror, Survival, Monster, Hard Sci-Fi, Body Horror |

| Director | John Carpenter |

| Cinematographer | Dean Cundey |

| Production Designer | John J. Lloyd |

| Costume Designer | Ronald I. Caplan |

| Editor | Todd C. Ramsay |

| Time Period | 1980s |

| Color | Warm, Saturated |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.35 – Anamorphic |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Side light |

| Lighting Type | Practical light |

| Story Location | Antarctica > US National Science Institute Station |

| Filming Location | Alaska > Juneau |

| Camera | Panavision Panaflex, Panavision Gold / G2 |

| Lens | Panavision C series, Panavision E series |

The technical execution of The Thing rests heavily on its groundbreaking practical effects. Made before CGI was a viable crutch, the film relied on puppets, prosthetics, and slime. The cinematography was instrumental in making these effects believable. Cundey’s camera doesn’t hide the work; he lights the creatures to give them weight and dimension, allowing the intricate detail of Rob Bottin’s creations to hold up even in close-ups.

The famous defibrillator scene, where a character’s chest opens into a maw, is a marvel of practical ingenuity. Using a real-life amputee for the shot allowed for a practical effect that felt physically impossible. Cundey’s framing ensures the moment is shocking yet convincing. It’s a reminder that limitation breeds creativity.

- Also read: MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL (1975) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: CASINO (1995) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →